With Snoopy and Charlie Brown back in cinemas, Nick Pinkerton explores the legacy of Charles M Schultz and other innovative cartoonists.

A few years before the Death of Cinema discussion reached a deafening din, there was the Death of the Comic Strip. Rather than competition from the small screen, the issue was disappearing page real-estate, stuffing more and smaller panels into an ever-contracting layout to service an ever-shrinking audience. Perhaps the medium’s most eloquent eulogist was also one of its last universally-esteemed artists, Bill Watterson, the creator of ‘Calvin and Hobbes’, who declared his cause lost and retired, his final strip running on New Year’s Eve, 1995.

In March that same year, Berkeley Breathed, who’d also bemoaned the slow smothering of the “funny pages”, began the first of what would be a series of retirements, wrapping up his Sunday strip, ‘Outland’, a sequel of sorts to his remarkable ‘Bloom County’, which first appeared in 1980. Even Gary Larson, whose single-panel ‘The Far Side’ seemed best equipped to survive the Great Shrinkage, closed up shop on New Year’s Day, ’95. Over the course of a single year, the brightest lights of a generation of American newspaper cartoonists went dark.

“It’s just a page of inky blur that only a 10-year-old’s eyes could focus upon,” Breathed told an interviewer in 2001 of the state of the art. “It’s the buggy whips of this millennium: quaint and eclipsed.” It hadn’t always been so. Once, said Breathed, “comic heroes were America’s first celebrities, known coast to coast.”

The comic strip and the motion picture, in their modern forms, are roughly contemporaries, two emissaries of a new mass media visual culture born at the dawn of the 20th century which, through a process of creative cross-fertilisation, together drafted and refined a vocabulary for graphic storytelling. The Yellow Kid, generally considered the first breakout comic star, first appeared in Richard F Outcault’s ‘Hogan’s Alley’ on 17 February, 1895 – the year usually given as the birthday of motion pictures for the lack of any more viable candidate. (The status afforded the Yellow Kid reflects a tendency to view comic strips as a Yankee invention, though England’s “Ally” Sloper appeared in the pages of ‘Judy’ as early as 1867 – and first appeared in a live-action film in 1898.)

Outcault’s initial outlet was Joseph Pulitzer’s ‘New York World’, though the Yellow Kid character proved so popular that William Randolph Hearst’s ‘New York Journal’ hired he and the Kid, shortly before that paper began, in 1897, to run Rudolph Dirks and Harold H Knerr’s ‘Katzenjammer Kids’. That same year the Lubin Film Company of Philadelphia released a cash-in short titled Yellow Kid, with the American Mutoscope Company’s The Katzenjammer Kids in School from 1898 arriving hot on its heels.

Meanwhile, out west, a young artist who was honing his draftsmanship at the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, Windsor McCay, saw a demonstration of Thomas A Edison’s Vitascope at a dime museum on Vine Street. Soon he would be headed off to join the staff at James Gordon Bennett, Jr’s ‘New York Herald’, where his work would briefly appear alongside Outcault’s new strip, ‘Buster Brown’, and where he would continue to dream of the new possibilities afforded by Edison’s invention.

In the early years of the movies, when framing still largely followed the model of the theatrical proscenium arch, comic artists were experimenting with the panoply of “cinematic” techniques in strips that now appear as forerunners to the storyboard. Initially, however, the newspapers were tapped for content, for characters and scenarios with proven appeal. Early film pioneer Edwin S Porter, of The Great Train Robbery fame, directed Buster Brown shorts for the Edison Manufacturing Company, as well as a 1906 film from McCay’s ‘Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend’ series, which depicted tempestuous nightmares brought on by the consumption of Welsh rarebit before bed.

Best known as the creator of the ‘Little Nemo in Slumberland’ strip, McCay’s illustrations of dream states would lead some to label him a proto-surrealist – a gag from ‘Rarebit Fiend’ recurs in Luis Buñuel’s 1930 short, L’Age d’Or – although his legacy in motion pictures is tied up with his role as a pioneer of film animation. Inspired by his son Robert’s flip books, McCay self-financed 10 animated shorts between 1911 and 1921, including 1911’s Little Nemo and 1913’s Gertie the Dinosaur, both of which he incorporated as interactive elements of his vaudeville act, before Hearst buffaloed him away from flights of fancy and into editorial work.

Soon it became de rigueur for characters to shuttle between screen and printed page, with Hearst and his King Features Syndicate leading the way in multimedia brand synergy. George Herriman’s ‘Krazy Kat’ got the animated treatment in 1916, as did Bud Fisher’s ‘Mutt and Jeff’. (Also, beginning in 1911, the basis for a series of one-reelers from David Horsley’s ‘Nestor Comedies’.) Felix the Cat, who first appeared in a series of animated shorts around 1919, got his own strip for King in 1923. EC Segar added a sailor with ballooned forceps to the cast of his Thimble Theatre in 1929, and four years later Max and Dave Fleischer’s Fleischer Studios produced the first Popeye the Sailor Man shorts. In his ‘Minute Movies’ strip, cartoonist Ed Wheelan, using a recurring company of invented matinee idols, illustrated the movies in his own mind.

Cartoons became comic strips, comic strips became animated shorts, and strips became live-action films. The 1920’s brought strip-to-live-action crossover acts including 1926’s Ella Cinders, Bringing Up Father, and Harold Teen (both from 1928), but the greatest dual-medium success of the era was undoubtedly Blondie, created in 1930 by Chic Young and carried by King, which spun off a grand total of 28 films starring Penny Singleton and Arthur Lake as Blondie and Dagwood Bumstead. Those who wanted to see still more of the Bumsteads could turn to any number of “Tijuana Bibles”, illicit underground comics which imagined prominent figures of the day as they engaged in (usually quite verbose) episodes of explicit conjugal bliss. Comic strip figures were popular subjects, as were stars of the silver screen – see for instance Laurel and Hardy in Doing Things, William Powell and Myrna Loy in Nuts to Will Hays, or Charlie McCarthy in Using a Wooden One.

Limiting ourselves to cases of adaptation, however, we will barely get at the paramount importance that comic strips had in shaping the imaginations of generations of filmmakers. A few examples: Georges Méliès, early in his career, was a political cartoonist. José Guadalupe Posada, a prolific printmaker who contributed to the penny press – the Mexican national equivalent to the comic pages at the turn of the last century – created an entire iconography for representing his native land, drawn on by Sergei Eisenstein in ¡Que viva México! and by the film artists of the coming Cine de Oro. (The conjoined history of Japanese cinema and manga probably deserves its own standalone piece.)

Federico Fellini, a devotee of American strips like ‘Happy Hooligan’, eked out a paltry living in Florence as a teenager by selling sketches to the satirical weekly ‘420’, and remained an inveterate doodler through his life. Sam Fuller also dabbled, illustrating his World War Two combat journals with drawings in the style of Billy DeBeck. (His brother, Ving, was the staff cartoonist at the lurid ‘New York Evening Graphic’ where Sam had been a teenaged crime reporter.) Between 1983 and 1992, polymath David Lynch contributed a strip called ‘The Angriest Dog in the World’ to the weekly ‘LA Reader’, always of the same four panels, three depicting the titular torpedo-shaped dog straining at its leash during the day, one the same scene at night, and the same ominous prologue: “…He cannot eat. He cannot sleep. He can just barely growl…”

Alternative weeklies like the ‘Reader’ were incubators for innovative new talents working in the strip format, including Mark Beyer and Matt Groening, though movie producers paid little heed to these developments. The Jazz Age boom of strip adaptations was never repeated, but Hollywood would continue to periodically test the public’s collective nostalgia for the Golden Age of Cartooning, producing the box-office debacle of Robert Altman’s live-action Popeye in 1980, John Huston’s Annie in 1982 and Dennis the Menace in 1993, a bowdlerisation of Hank Ketcham’s strip which was part of a post-Home Alone bumper crop of movies starring awful children. These films appeared during the Indian summer of newspaper cartooning as a popular art, the era of Breathed, Larson, and Watterson none of whom had any impact on cinema, per se. Breathed and Larson tried television shorts, while Watterson was a cartooning-as-cartooning purist who refused to license out his creations – among the subjects discussed in Joel Allen Schroeder’s 2013 documentary Dear Mr Watterson.

Charles “Sparky” Schultz, the dean of American cartooning from the mid-century onwards, never had any such compunctions about cross-promotion, lending his ‘Peanuts’ characters to a series of well-loved television specials produced in collaboration with Bill Melendez, beginning with 1965’s A Charlie Brown Christmas. While the best and brightest Boomer talents abandoned ship, Schultz held on until 2000, when he essentially died at his drawing table, having turned out discursive, dottily-charming, and increasingly gag-free ‘Peanuts’ strips to the end of his days.

With this, the field was ceded to hacks whose work had little to lose from formatting changes that devalued draftsmanship, as the smart phone and computer screen devalue mise-en-scène. After the great abdication, the rulers of the barren kingdom that the funnies had become were Scott Adams, with his postage-stamp-frame ‘Dilbert’, and the hackiest of them all, Jim Davis, whose endlessly repetitive ‘Garfield’ strips were an afterthought in his Paws, Inc merchandising juggernaut.

Of course, Davis would eventually get his paws into feature films with 2004’s Garfield: The Movie, whose mixture of computer animation and human actors is representative of a 21st century cinema that has made firm designations like “live-action” and “animation” problematic. The film’s Garfield, with his every orange-and-black hair articulated, epitomised a new difficulty in strip-to-screen translation – the CGI hyper-realism ruins the line, a cartoonist’s signature and the source of whatever charm his creations have. (The less said of 2010’s Marmaduke, the better.)

Preliminary glimpses of Bly Sky Studios’ forthcoming The Peanuts Movie suggest great pains have been taken to retain Schultz’s style, though whether the film will embody what cartoonist Ivan Brunetti called Peanuts’ “simple, beautiful, empathetic glimpse into the human condition” remains to be seen. Whatever the case, when tracing over the work of an Old Master, we’re very far removed from the once-lively dialogue between strip and screen.

Charlie Brown and Snoopy: The Peanuts Movie is released 21 December.

Published 14 Dec 2015

America’s most famous loser/dog comic strip combo graduate to the big screen with charm and ease.

LWLies reports from the beguiling Bay Area basecamp of one of the world titans of feature animation.

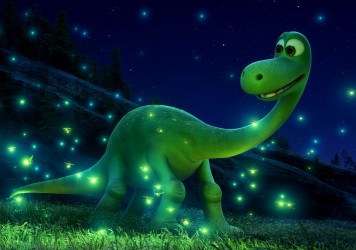

This prehistoric psychedelic western is Pixar’s strangest and most spectacular work to date.