Isao Yukisada’s Go has three beginnings. The first is a text quote from Shakespeare: “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet”. Coming from Romeo and Juliet, this suggests that we are about to watch a tragic romance between mismatched lovers.

The second shows protagonist Sugihara (Yosuke Kunozuka) – though that is not his ‘real’ name – being isolated and bullied on a school basketball court by the other players. As he recites in voiceover the mainstays of Japanese ideology and identity – “Race, homeland, nation, unification, uh, patriotism, integration, compatriots, goodwill” – only to dismiss them all with the words, “Makes me sick”, he turns roaring on his persecutors, kicking and punching his own teammates, the players on the other side, and even the adult coaches, before his narration declares, incongruously amid all the violence, “This is my love story.”

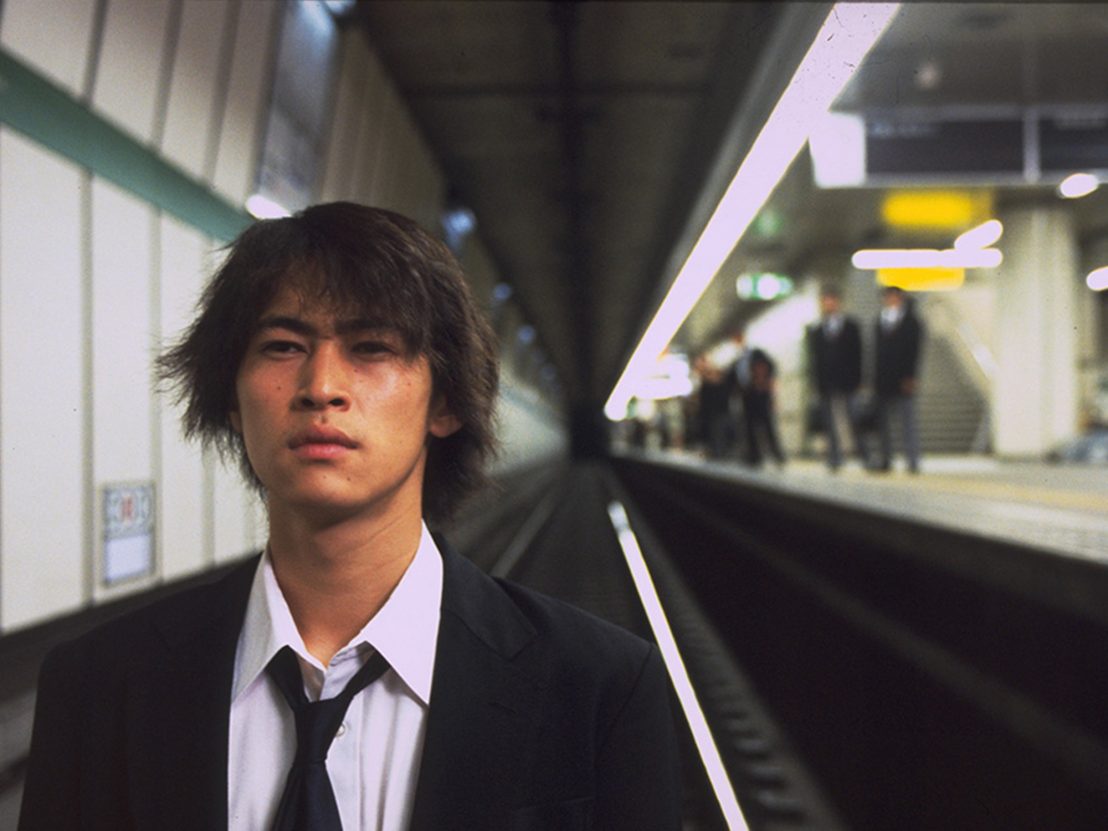

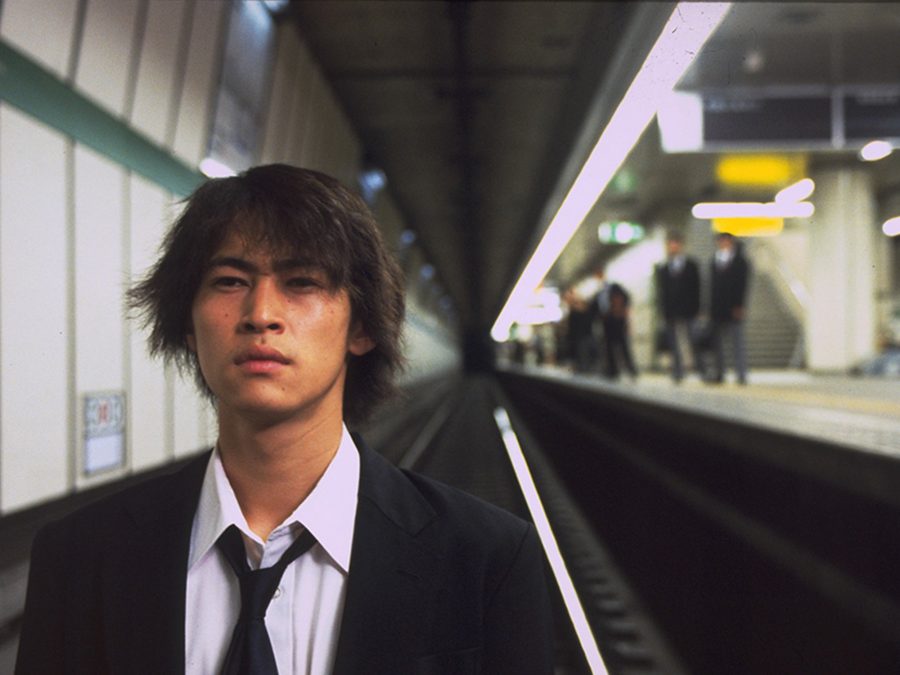

The third, set three years earlier, shows Sugihara engaging in a dangerous game, known as the ‘Super Great Chicken Race’, on the Tokyo subway, as he outruns an approaching train on the tracks and flees with his schoolmates, only to be arrested outside by pursuing police. Here Sugihara is all at once fearless, fugitive and unstoppable – at least until he is stopped.

This triptych of sequences establishes both the key themes and the overriding tone of Go. For this is to be a vibrantly dynamic coming-of-age story, playing out Sugihara’s rebellious adolescence and confused sense of identity with equal speed and swagger, even as it switches between Sugihara’s different experiences at the high school he was at in the recent past, and the one he is in now. And it will also, as Sugihara insists, be a love story. Most of all, though it is a portrait of Japanese society at its most insular, discriminatory and exclusive, where a misfit like Sugihara will always struggle to find his place.

Sugihara is a Zainichi, or Korean-Japanese, and his inner conflicts and confusions are very much a product of his upbringing and environment. “You didn’t have to go to family court – be grateful”, his North Korean father Hideyoshi (Tsutomu Yamazaki), an ex-pro boxer, tells his son after giving him a vicious, bloody beating at the police station. “Say thank you,” adds his Japanese mother Michiko (Shinobu Otake). Sugihara has learnt brutality early, both at home and beyond – and the love/hate relationship that he has with his father extends to the country where he was born but barely belongs.

Much as Hideyoshi reluctantly changes his nationality from North to South Korean to make it easier to take a holiday to Hawaii, Sugihara insists on changing from his North Korean junior high school in Tokyo (where only Korean can be spoken, and where teachers impart lessons with their fists) to a Japanese high school whee he hopes to become more naturalised. Yet like his father, Sugihara will never be fully accepted, and when he finds himself bullied by the very Japanese pupils with whom he had been trying to integrate, he discovers the utility of the fighting skills that Hideyoshi has passed down to him.

Sugihara’s martial prowess and general recalcitrance attract the attention of fellow pupil Sakurai (Ko Shibasaki), who recognises this outsider as ‘cool’ – but as their relationship blossoms, its taboo nature as forbidden love comes to the fore. Sugihara, nicknamed ‘Stupid’ by his Zainichi friends, and really called Lee Jong-ho before he adopted a more Japanese-sounding name, will learn that he does not in fact smell as sweet by any of these names. For while he can sometimes pass for Japanese, he will always, once his identity is revealed, be an impure foreigner in xenophobic Japan, and so must play Romeo to Sakurai’s Juliet, and face a generalised racism that even she has thoroughly internalised.

Adapted by Kazuki Kaneshiro (himself a Zainishi) and Kankuro Kudo from Kaneshiro’s semi-autobiographical 2000 novel of the same name, Go was the first joint Japanese/South Korean production, and received a simultaneous theatrical release in both countries, even as it uses an unorthodox romantic frame to find rapprochement between the two nations (three really, as Sugihara shares his pariah status with that of his father’s homeland, North Korea). Of course, every teenager at times feels like an outcast both at home and abroad – but Sugihara’s awkward, often brutal rites of passage reflect in reverse the growing pains and immature identity of an island nation more than capable of alienating even those who were born there.

Go comes with a happy ending of sorts, on a snowy Christmas Eve whose clichéd chocolate-box nature even Sakurai acknowledges – but even if ultimately this couple will overcome their differences and find love together again, the example set by the previous generation, with Korean Hideyoshi and Japanese Michiko repeatedly splitting up and regularly unhappy, suggests that a rocky road lies as much ahead of as behind our star cross’d lovers.

Go is released on Blu-ray by Third Window Films, 22nd May, 2023.

Published 22 May 2023

Saoirse Ronan experiences growing pains in Sacramento in Greta Gerwig’s delightful indie comedy.

By Anton Bitel

Yasuzô Masumura’s Giants and Toys from 1958, about rival confectionary companies, shows a nation in flux.

The ’90s straight-to-video boom reinvigorated the industry and made stars of directors like Takashi Miike.