In the wake of sexual assault allegations made against Kevin Spacey, Netflix have announced that the upcoming sixth season of House of Cards will be the last. Production in Baltimore has been halted, and it is currently unknown if the series’ swansong will air as planned in mid-2018. This announcement was not met with much surprise by fans of the show, who had long-since suspected that House of Cards had nowhere to go once Frank Underwood’s nefarious antics became increasingly believable in light of Trump’s presidency. Even so, the death of the OG Netflix original does suggest implications for the binge-watch culture which it helped to spawn.

There’s no denying the wide-ranging influence that House of Cards has had on the TV landscape. Back in 2013, the reimagining of a little-known British show from the 1990s as a taut American political thriller starring Academy Award-winner Spacey played a big part in securing Netflix’s future not only as a streaming giant, but as a viable content creator in its own right, rivalling the likes of studio titans HBO and NBC.

Streaming platforms have so far been reliant on the novelty value of dropping a whole series all at once to demand the attention of viewers. At first the business model seemed peculiar, but audience responses quickly prompted other platforms to follow suit and even create original content for the express purpose of a series drop. The marvel of being able to consume a brand new season or series months or even years in the making in the space of a single weekend is satisfying in its own right, and Netflix in particular have been able to ensure a captive audience by timing the release of binge-worthy shows right, as in the case of Stranger Things 2’s timely arrival over Halloween weekend.

Prior to the dawn of online streaming and the instant gratification provided by binge-watching, a series would typically play out over the course of weeks or even several months. So-called ‘water cooler’ moments such as JR’s shooting on Dallas or The Sopranos’ unforgettable finale got their name from the excited conversation they sparked among office workers the morning after the episode aired. Binge-watching has undoubtedly altered the process by which we consume television, with many dedicated fans racing to get through hours of programming in as little time as possible. Water cooler moments no longer exist, as audiences consume shows at their own pace, and fear of spoilers limits word-of-mouth appeal.

Without the old-school buffer period of a week between episodes it’s hard to know how much of a series audiences are really digesting, or if a show can have as much impact when it is just the latest offering from a production line of bulk-release series. Consider the shelf life of a box set series: after the initial hype dies down, this cannot be replicated across subsequent seasons, even for flagship titles such as Stranger Things and Orange is the New Black. With social media often serving as an echo chamber, and Netflix tight-lipped on viewing figures, there’s an undeniable potential for series designed to be consumed in a short period of time to fade into the internet ether.

Studios have a solution, and the growing trend towards franchisation of television properties runs in line with boxset culture. Breaking Bad’s staggering popularity came about after many viewers discovered it on catch-up and streaming services, and spawned AMC/Netflix spin-off Better Call Saul. Similarly, AMC’s binge-tastic The Walking Dead led to Fear the Walking Dead, and Netflix is currently in talks to develop up to three House of Cards spin-off series, hoping to breathe new life into their established brand.

In fact, many streaming services have since opted to trial weekly releases, as Hulu did with The Handmaid’s Tale and Amazon and Netflix do with syndicated content such as American Gods and Riverdale. They have made their platforms a place which viewers must return to week after week in order to access their content, but more importantly, while these series may have previously only found a home on satellite channels, affordable online streaming services have made television more accessible to audiences than ever before. Meanwhile, traditional networks look to a new breed of ‘event television’ attempting to reject binge-watching and catch-up culture by broadcasting to cinemas, such as BBC’s Sherlock and Doctor Who and Marvel’s Inhumans. Results have been mixed at best.

Increasingly Netflix is looking to the other arm of its original programming to attract conversation. High-profile feature film work with directors including Noah Baumbach, Bong Joon-ho and Angelina Jolie has been met with some resistance by the mainstream film world, with Bong’s Netflix backed Okja receiving boos from the audience at its Cannes premiere. Despite remaining tight-lipped on their respective plans for the future, Netflix and their largest rival Amazon now seem interested in producing prestige cinema that can compete with Hollywood.

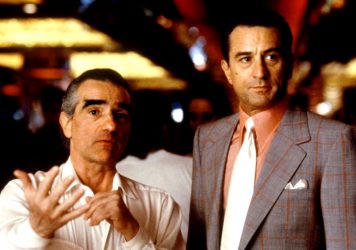

While most titles are released direct-to-platform, Netflix have also experimented with giving their films a limited theatrical run before making them available online. Gone are the days when you had to catch a film at the cinema or else wait up to a year for the DVD or Blu-ray – with Netflix, you might only have to wait a week. One upshot of this is that Netflix have made certain films more widely accessible – particularly in regions where the latest Baumbach or Bong flick might not be showing – but it’s a double-edged sword. Take Martin Scorsese’s highly anticipated The Irishman, which was acquired by Netflix earlier this year. It’s hard to think of a more cinematic filmmaker, and reconciling directorial style with distribution intent is a relatively new concept.

Netflix may have pioneered binge-watch culture, but it by no means perfected it, and as one show is put out to pasture, the made-to-stream production line rumbles on. Where broadcasters go from this point on is anyone’s guess, but as shows fight for space in an increasingly saturated market, the novelty of binge-watching and the freedom to stream at home just isn’t enough of a hook anymore.

Published 1 Nov 2017

The streaming service has bought the international rights to the directors’ long-gestating crime drama.

By Elena Lazic

The writer/director of The Meyerowitz Stories reveals how he mixes the comic with the tragic.

By Amy Bowker

The director has spoken out about the streaming giant’s involvement in his latest project.