Given his notoriously cryptic way with those interviewers seeking answers to what are invariably the wrong questions when it comes to his work, it would be a fool’s errand to expect David Lynch to suddenly spell things out in his wonderful new book, ‘Room to Dream’. That said, perhaps one seemingly indestructible debate can finally be laid to rest, at least as far as its maker is concerned. “It was never television for David,” notes production coordinator Sabrina Sutherland of his long-awaited return to the world of Twin Peaks last summer, “It was always a feature film.”

If it seemed like a tiresomely banal question to ask of a filmmaker whose work has always proved resistant to the binaries of definition, it’s one on which the very existence of Twin Peaks: The Return hinged. “Showtime had it in their heads that this was episodic television and didn’t understand David’s vision,” continues Sutherland. “[He] wanted a complete feature-film crew there every day, including lightning machines, standby painters, and special-effects technicians, and that isn’t how television works.” Lynch walked away from the meagre deal, citing creative differences, only returning when a viral campaign from his cast members brought the network to their senses. Lynch himself puts his response to the contractual debacle more succinctly: “Fuck this! I’m fucking out!”

The filmmaker who The Elephant Man producer Mel Brooks once described as dressing “like Jimmy Stewart about to star in a film about Charles Lindbergh” has an easy way with an F-bomb; his fucks jostling for space with archaically wholesome slang. For an artist whose career was built on devilling the optimistic surfaces of Americana, such linguistic tension feels appropriately and singularly, well, Lynchian.

At once biography and autobiography, ‘Room to Dream’ sees each of its chapters divided into two parts. The first is traditionally researched by Los Angeles Times critic Kristine McKenna, who conducted over a hundred interviews with personal and professional collaborators, while the second offers Lynch’s own take on the period covered. “What you’re reading here is basically a person having a conversation with his own biography,” the introduction has it, “A chronicle of things that happened, not an explanation of what those things mean.” As such, it’s the most comprehensive overview of the filmmaker’s life and career to date.

What finally emerges across some 500-odd pages is a humanising portrait of an intuitive working method, a process of approaching the creation of a work of art that in turn provides the key to the audience’s understanding of it. “We read his images at some not fully conscious level,” wrote Pauline Kael of Blue Velvet, and to read Lynch describe the evolution of Mulholland Drive is to sense a subconscious over an intellectual instinct at play: “There’s a unique blue key to something unknown. There had to be something it was to, and I don’t know why it ended up being to a blue box instead of a door or a car.”

Cast and crew would be none the wiser to Lynch’s various endgames, while ever willing to trust and facilitate a path through his imagination. “Wear a bunny suit you can’t breathe in that’s seven thousand degrees inside? I don’t care; I’ll do it for David,” says Naomi Watts, “[He] never explained to us what we were doing. We just followed his instructions.” Script supervisor Cori Glazer describes being roped in at the last minute to play Mulholland Drive’s Blue Lady, with no idea of how the character would fit into the story, “David’s favourite thing to say is, ‘I don’t care – it’s modular!’”

While McKenna’s biographical journey through Lynch’s life eschews anything approaching textual analysis, it’s not without keen insights to approaching the work itself. “Lynch prefers to operate in the mysterious breach that separates daily reality from the fantastic realm of human imagination and longing, and is in the pursuit of things that defy explanation or understanding,” she writes, “He wants his films to be felt and experienced rather than understood.”

This ongoing pursuit of the intuitive has alternately earned him legions of fans and alienated them, as evidenced by the rapturous reception to the first series of Twin Peaks and its subsequent 1992 spin-off feature, Fire Walk with Me. “[He’s] disappeared so far up his own ass that I have no desire to see another David Lynch movie,” said Quentin Tarantino of the latter. Not that Lynch appears to give a shit about his work’s critical reception. As McKenna writes of Lost Highway’s 1997 opening, “Lynch reminded the film community that he wasn’t making movies for them and was answering to the higher authority of his own imagination.”

Lynch suggests this refusal to compromise on his artistic vision harks back to the terrible experience making Dune for Dino De Laurentiis, a for-hire gig that saw him without final cut for the only time in his career. He’d learned his lesson by the time it came to Twin Peaks, as co-writer Mark Frost recounts, “I remember an executive taking a list of notes out of his pocket and saying, ‘I’ve got some notes if you’re interested,’ and David said, ‘No, not really,’ and the guy quietly put the list back in his pocket with a sheepish look on his face.”

The inimitability of Lynch’s work is best borne out in the lacklustre second season of Twin Peaks, in which he’d largely divested his involvement. “People would come in and put a kaleidoscope on the camera and say, ‘Oh look, how Lynchian,’” notes actress Kimmy Robertson. His work is explicitly personal, and Lynch’s own telling of a youth spent in the idyll of Boise, Idaho and a young adulthood on the dangerous streets of Philadelphia a decade later portrays opposing visions of an America he’d look to reconcile. Not that said tension wasn’t perceptible from the start, as recollected in a childhood encounter that would give birth to Blue Velvet’s Dorothy Vallens many years later:

“We were down at the end of this street at night, and out of the darkness – it was so incredible – came this nude woman with white skin. Maybe it was something about the light and the way she came out of the darkness, but it seemed to me that her skin was the colour of milk, and she had a bloodied mouth. She couldn’t walk very well and she was in bad shape, and she was completely naked… I might’ve asked, Are you okay? What’s wrong? But she didn’t say anything. She was scared and beat up, but even though she was traumatised, she was beautiful.”

If there’s a constant to Lynch and McKenna’s account, it lies in an insatiable work ethic present from the very start. For those only familiar with Lynch’s cinematic output, ‘Room to Dream’ serves to contextualise the films within his broader work as a multidisciplinary artist. One gets the sense that the greatest personal profit of an entire working life, has been the space to follow his muse. Personal relationships have clearly suffered along the way, and while the book’s introduction states that “nothing was declared off-limits,” there’s little by way of self-criticism on Lynch’s part.

“David is like catnip to women,” notes McKenna, and it’s hard to keep up with his myriad romantic entanglements. “There’s no malice in Dad and he doesn’t do these things out of selfishness,” says daughter Jennifer Lynch, “It’s just that he’s always been in love with secrets and mischief and sexuality, and he’s naughty and he genuinely loves love. And when he loves you, you are the most loved, and he’s happy and giddy and he has ideas and gets creative and the whole thing is insanely romantic.”

Yet it’s hard not to think there’s a flip side to that coin. All the women in Lynch’s life speak highly of him – all of his collaborators do – but not without a note of fond resignation lurking between the lines; an awareness that they’ll always come second to his own private muse. There’s genuine sadness to be found in his fourth wife Emily Stofle’s account of his moving out of the marital bedroom during the making of Twin Peaks: The Return to a space that would allow him time to smoke and think.

Maybe it’s the cost of the artistic life, or simply the nature of an authorised account of it. It would be remiss to put anything past such an uncompromising artist as Lynch. As Twin Peaks’ Michael Ontkean says, “You don’t see the strings or the wires or the rabbit unless David wants you to.”

Published 19 Jun 2018

By Adam Nayman

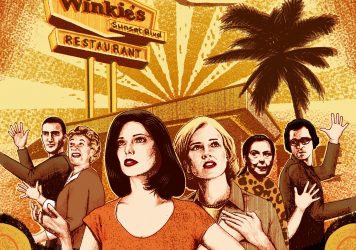

Is David Lynch’s warped Tinseltown satire from 2001 a contemporary riff on one of Hollywood’s classic-era staples?

By Alex Denney

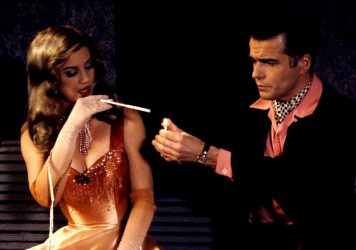

The original cast and crew discuss the making of this short-lived follow-up to Twin Peaks.

Exploring the director’s use and manipulation of music in his 30-year-old masterpiece.