The decades-long friendship of Noah Baumbach and Brian De Palma proves that opposites really do attract. Despite sharing little in style, the pair have swapped drafts and early cuts since 1996 – although De Palma turned down a role in Mr Jealousy he instead offered feedback on the project. Unsurprisingly, then, Baumbach’s new film is more than just a career-spanning documentary; it sees him and co-director Jake Paltrow pay tribute to their childhood idol and artistic mentor.

In terms of structure, De Palma is simple and enthralling. It’s essentially one long conversation mixed with relevant clips: De Palma speaks candidly to the camera about surviving Hollywood horror stories, the recurrence of actors who don’t learn their lines, and other tricks of the trade he’s learned along the way. By the end, you start to get a sense of what it feels like to routinely pick up tips from a master filmmaker.

So why aren’t De Palma’s fingerprints all over Baumbach’s work? Although Baumbach grew up watching the likes of Dressed to Kill and Body Double, any lasting effect isn’t immediately obvious. Greenberg isn’t shot with split-screen sequences, and Frances Halliday isn’t a voyeur with a telescope. Yet there is actually plenty of overlap in the films of Baumbach and De Palma, it simply requires us to zoom in a little closer.

As seen in: The Squid and the Whale (2005)

Judging from the awkward book Q&A scene in Margot at the Wedding, Baumbach did not appreciate the personal questions he was asked while doing press for The Squid and the Whale. Nevertheless, it’s an inescapable thought when watching any Baumbach film – especially when, say, Jennifer Jason-Leigh has a story credit for Greenberg. With his De Palma documentary, though, the ludicrous thrills and perverse kills are assumed to be fictional. But are they? Among the film’s many surprises, De Palma describes Raising Cain as a “family album,” Home Movies as “stories about my family,” and aspects of Body Double as “stuff I’ve lived.”

Perhaps the most personal is Dressed to Kill, the outrageous B-movie starring De Palma’s then-wife Nancy Allen. “Keith Gordon’s character came from me and my science projects,” the director recalls. “I used to follow my father around when he was cheating on my mother. I took photographs.” The museum set-piece, he goes on to explain, evolved from a genuine hobby of chatting up women at MoMA, and Michael Caine’s role was modelled on an ex-therapist. A lesson for Baumbach: disguise real-life elements with Hitchcockian twists to throw off journalists.

As seen in: Frances Ha (2012)

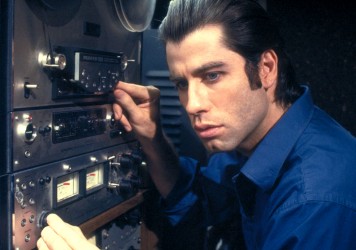

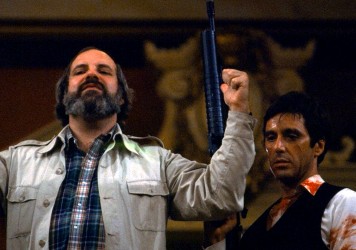

If Hitchcock is a language, then De Palma has been fluent in it for decades: Obsession is Vertigo, Body Double is Rear Window, and so on. “I was the one practitioner that took up the things he pioneered,” De Palma asserts in Baumbach’s film. Alternatively, there’s Blow Out – often deemed the most representative of his aesthetic – which recalibrates Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up through a pulpy lens. Baumbach, on the other hand, waited until Frances Ha for an inarguable homage to classic cinema: Greta Gerwig bouncing along the pavement to David Bowie’s ‘Modern Love’, emulating Denis Lavant in Leos Carax’s Mauvais Sang.

“I’ve become more open to Brian’s Mt. Rushmore idea,” Baumbach recently observed in an interview with The New Yorker, “that you come up with characters and a story to justify a great visual set piece.” This, he adds, led to, “having Frances running down the street and figuring out what that had to do with anything later.” Carax’s movie may have provided the filmic grammar and immediate inspiration, but Gerwig is really sprinting with the spirit of De Palma.

As seen in: Mistress America (2015)

For the Criterion release of Dressed to Kill, Baumbach cross-examined De Palma on the gripping 10-minute sequence in which Angie Dickinson is pursued across a vast museum. “It’s very important when you go to a space, to walk around it,” De Palma explains to a nodding Baumbach. “Take photographs. See what’s unique about the space… have them look in various ways so the audience gets acclimated to the geography of the location.”

This patient build-up is a De Palma staple, from the first shootout of Carlito’s Way to the pre-bloodbath prom scenes of Carrie. Similarly, in Baumbach’s Mistress America, a house tour sets up the elaborate second act’s double-crossing, eavesdropping and squabbling over a chess set. Gerwig and her gang are led through the ground floor and, as with Dressed to Kill, they scrutinise the decor (“this place is amazing,” “it’s really fucking nice,” “are those my cats?”). And then everyone splits up for intersecting subplots. As De Palma tells Baumbach: “The chess game can begin, but you’ve got to know the board.”

As seen in: While We’re Young (2015)

“I steal from everyone: Wiseman, Maysles, Pennebaker,” Ben Stiller’s frustrated documentarian admits in While We’re Young, Baumbach’s feature-length riff on how generations of filmmakers squabble amongst themselves. Of course, the plot is fictional – despite rumours of a dig at Joe Swanberg – and yet Stiller takes his latest project to his father-in-law (Charles Grodin), a grumpy filmmaking legend, for a second opinion.

“This was the Warner Bros youth group,” De Palma says about himself, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese and Paul Schrader in the ’70s. “We were all incredibly supportive of each other, passing scripts back and forth, looking at each other’s movies.” Nowadays, De Palma’s cinephile BFFs are Baumbach, Paltrow and Wes Anderson. Their filmmaking philosophies may seem contradictory, but that means common ground must be taken seriously. For instance, when Baumbach mentioned the possibility of casting Gerwig in Greenberg, De Palma did his homework: “I said, ‘Who’s Greta’?’ And I looked at every mumblecore movie and said, ‘My god, she’s really good!’”

As seen in: Everything

Towards the end of De Palma, when 2012’s Passion is discussed, De Palma addresses Baumbach and Paltrow (both unmic’d) on their shared indie terrain. “I’m returning to the kind of movies you guys are making,” he tells them. “You’re adjusting to the system. If you want to make personal movies with personal ideas, you have to make them at a budget.” Judging by De Palma’s tales of Mission to Mars (a $100m disaster) and Mission: Impossible (Tom Cruise’s ego trouble), Baumbach was advised a long time ago to turn down Hollywood.

“You make a certain kind of movie because that’s the way you see things,” De Palma explains, “and these images keep recurring again and again in these movies. That’s what makes you who you are.” Baumbach, like De Palma, is often accused of repeating himself, or at least sticking to the same dialogue-heavy style, but even sceptics couldn’t call his work “impersonal”. At the documentary’s NYFF press conference, Baumbach was asked how De Palma affected his work, to which he responded, “Isn’t it obvious?” He may have been joking, but the elusive answer is right there in his films.

De Palma is released 23 September.

Published 19 Sep 2016

Generational drift and the scourge of hipsterism are examined in Noah Baumbach’s bittersweet comedy of manners.

By Taylor Burns

Brian De Palma’s taut Watergate-era thriller highlights the difference between what a country believes itself to be, and what it actually is.

Noah Baumbach’s survey of the life and work of Brian De Palma is riveting and highly entertaining.