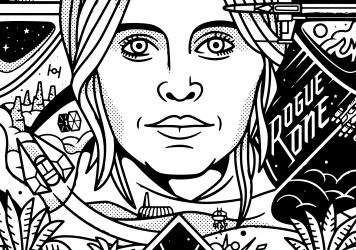

Inside the hyper-charged mind of the Rogue One: A Star Wars Story director.

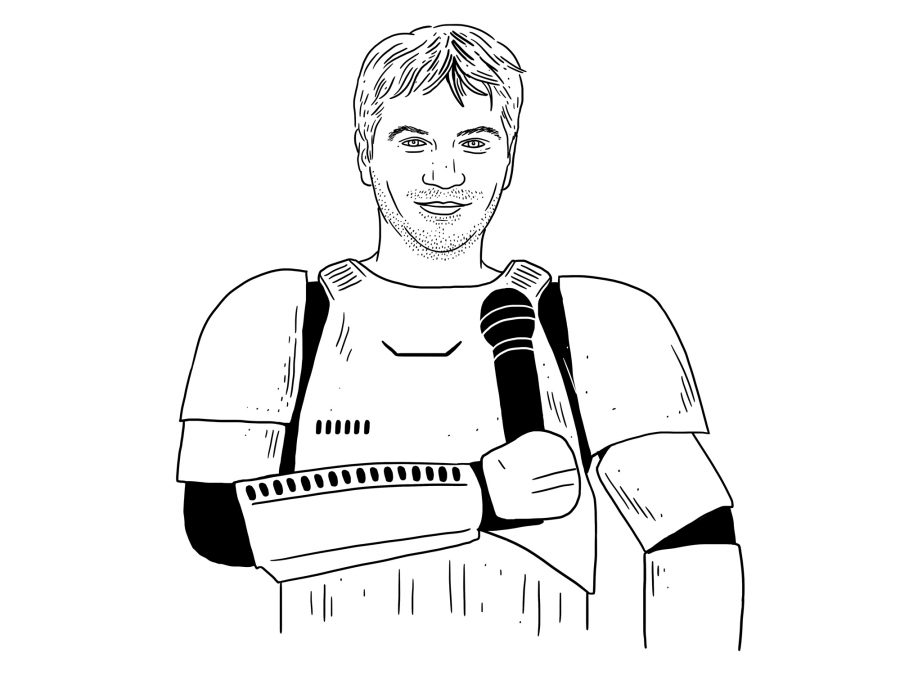

Let’s get the love-in out of the way early – British effects whiz-turned-expert blockbuster builder Gareth Edwards is one of our favourites. Everything was right there in his 2010 debut feature, Monsters, which fuses together a rough-hewn, semi-improvised realism with gorgeous, computer generated, hovering glow-in-the-dark squids. It was a low-budget labour of love which looked like it cost at least 50 times its minuscule $500,000 budget.

Hollywood was watching, and it wasn’t long before Edwards was over at Warner Brothers and handed the keys to a Godzilla reboot. The result remains one of the most majestic, awe-inspiring blockbusters of the modern age, an exemplary fusion of the classical disaster movie conventions with action sequences which often take on a near-experimental quality. Here was a director with the ability to personalise the impersonal, to stamp his imprint on a giant, looming edifice.

And now, Edwards has somehow tramped even higher up the mountain. Rogue One is the first of what is set to be a series of Star Wars “stories”, spinning out from the original, canonical saga. The film concerns a gang of rebel fighters, which includes Felicity Jones’ Jyn Erso, who are out to nab the blueprints for an under-construction Death Star. We spoke to Edwards about how he goes about making films on such a grand scale, and how he was able to pay lip service to George Lucas’s vision while adding something new and vital to the mix.

LWLies: Godzilla and Monsters were both slow-burn films which teased the audience with effects and a gradual crescendo. Have you done the same with Rogue One?

Edwards: You’d have to tell me. When we filmed Monsters, it was very organic, or whatever words you wanna use. It was opportunistic. It was a bit of a freeform thing: this is kind of the scene; this is kind of the idea. Just do what you want to do, and we’ll try and find the beauty in it. Godzilla was the polar opposite of that, so it was setting every single shot up, then putting marks on the floor and everyone has to hit them. It feels very contrived in my mind. And so, on this, I wanted to find that happy balance between the Hollywood approach to things and a more independent, freewheeling vibe.

What do you mean when you say ‘Hollywood?’

The idea of storyboarding everything. You stand there, you say that line, you walk to that corner, you look out there. It’s very controlled and structured. It’s great, in a sense, as nearly all of the classic blockbuster films are born out of that style. When I was doing visual effects, I learned that the thing that’s most exciting is when you find the thing you weren’t thinking of. Otherwise, all a film can ever be is what you’ve pictured in your head. As great as anyone might think they are, there’s a limit to what that picture can really be. The more you can add some of your own DNA to the mix the better. Fracture it. Try and create happy accidents. Suddenly you get things that are way better than you pictured. We tried to inject that approach into this film.

How do you create a happy accident?

Let me give you an example: there’s an area in the film called Jedah. We had a set that was 360 degrees. You normally have a bunch of background artists, and when you say action they walk from left to right. And when you say cut, everything is reset and you start over again. On this, we wanted it to feel like a real market. So instead of walking left to right, everyone had to learn what they did for a living. Like, they sold fruit on a stall, or they were an inspector…

Read more inside our Rogue One print edition

Buy nowSo everyone had there own little imaginary things that I had no idea about. These thoughts were theirs. It meant that they could keep going forever. So we could lm and not have to cut. We could look in every direction. The assistant directors are the ones who are running around in the background and if they’re not careful they get into shot – they wore costumes so they could walk into shot and not be seen. As a result, we ended up in this situation where the actors could go in and do their scene, but we could also find the beauty in it.

It feels more like the approach of an arthouse director than someone making a Star Wars movie.

It would’ve been impossible to do this for the whole lm. There were scenes inside spaceships and we had 180 degree LED screens. The flight path of the ship was pre-animated, and the whole thing was on hydraulics. We’d get locked inside, not come out for an hour and get very sweaty and hot. But we could just go again and again and again. I think that effect of being held hostage inside a tin can like that added to the performance. I don’t know… It’s much more for people like you to say. We were just trying to do it whenever we could. There’s definitely lots and lots of shots in the lm where I could say to you, ‘We never contrived that at all. That is just Diego [Luna] exhausted and on his knees and we suddenly ran around with the camera and got this shot.’ I never asked for that, but I’m so glad it happened. It’s a moment by moment thing.

You’ve talked about Alejandro González Iñárritu as being an inspiration on how you approached this. Is it possible to achieve that level of realism in the Star Wars universe?

I think if we weren’t doing this as a stand-alone movie, then probably not. But, what was good about being a spin-off was that we had a licence – if not a mandate – to be different. What is that difference? I just wanted things to be more natural. There’s no part of me that doesn’t watch those original films in total awe. Every one is a masterpiece. It’s not like there’s something you can do that’s better than that. I want people to feel when they’re watching Rogue One that they are really going to these places.

What about the original, classical fantasy style forged by George Lucas?

We are doing that too – the very classical, epic, considered and controlled ’70s Spielbergian old school style. We tried our best to mix and match things. And that’s one of the things I like about the film – that there’s the contrast between those two styles. That quick gear change keeps everything fresh. And it’s not as simple as Rebels are handheld and Empire is stable. There’s only beauty in contrast. You need the dark to feel the light, and vice versa.

From when you got the job to direct Rogue One, what was it then like to going and re-watching the original films?

I was terrified that it was going to ruin them for me. Star Wars has always been something that I could just put on. It always gives me goose bumps and it always reminds me why I love cinema. Then I think, what if I could never look at them again in the same way? As of today, it hasn’t changed any of that.

When you went back and watched the original films did you take copious notes?

On day one, we were in Lucasfilm in San Francisco with Industrial Light and Magic and John Knoll, our supervisor, he said that they’ve got a brand new 4K restoration print of A New Hope – it had literally just been finished. He suggested we sit and watch it. Obviously, I was up for that. Me, the writer, lots of the story people and John all sat down, we all had our little notepads, we were all ready for this. I’ll add that I’ve seen A New Hope hundreds of times. So I was sat there, ready to take notes and really delve under the surface of the film. You have the Fox fanfare, then scrolling text with ‘A long time ago…’, and then the main music begins. Next thing we knew it had ended, and we looked around to one another and just thought – shit, we didn’t take any notes. You can’t watch it without getting carried away. It’s really hard to get into an analytical filmmaker headspace with this film. It just turns you into a child.

“It’s really hard to get into an analytical filmmaker headspace with this film. It just turns you into a child.”

One thing that Star Wars does amazingly well is the character entrance. As a director, how do you choreograph a great entrance?

You can film a character entrance, but you can get to the edit and find that you can’t use it. It might take too much screen time to show that person in the way that you had planned. You have to cut and they’re on screen. There’s a particular character entrance in the film that I’m very proud of. It had to be special. And it’s probably obvious who it is.

How do you build those sequences?

It’s… a bit like the stops on a Tube map. Or connecting dots. You know what the story is, and you try and come up with visuals that are memorable and feel right. You come up with loads of them. An insane amount. And then you try to connect them in a scene. How can we get from this point to this destination, and go via here, here and here? Making a movie is about finding a path. What can happen is that, because you’re being visually led through a story, it’s not always the right approach. A film is like a child that you’ve raised to be a lawyer, but the child turns around and says it wants to be a fighter pilot. At a certain point, a film tells you what it needs to be. You just try and feed it ideas. And even though it will reject some of them, it’s nothing personal. It’s like a reflex reaction.

Is it always you who can see when something doesn’t work or do you have other people to look out for that?

People tend to be the ones look out for that. But there’s stuff that I’ll reject because I just won’t want it in the film. It doesn’t feel right. There were occasions where people said you don’t need this or that, and I held on to it. The downside is, if you have an object and everyone takes away everything they don’t like, if there’s enough people, you end up with a sphere every time – no edges, nothing of interest. I always try and take everything with a pinch of salt. Stay open minded and honest, but don’t lose the drive to make something unique. Honestly, it’s such a mindfuck. Right there, in those details, is the difference between making a good film or a bad one.

From the way you’re talking, those micro decisions would seem to be cripplingly stressful.

On Star Wars they are, because they last forever. For instance, the toys that get made. Say you’re designing a gun, and you come to a button on the gun and you’re thinking about the way it clicks. If you get into the detail of that stuff with the props people, you just think, stop being such an idiot, no one is going to see or care about this. But as soon as you say that, you remember: this is Star Wars, of course they’re going to see it and care about it. If you’ve done your job properly, people are going to be looking at that helmet for long time, not just for a split second on screen. It might end up on a t-shirt. You’ve got to be hard on it.

How difficult a task is it to always keep one eye on the bigger picture?

There’s two modes: you have the macro mode where you’re looking at structural stuff and pure story, then once you’ve got that right, you can zoom in to the micro mode. But it’s always possible that you zoom in too early – you can spend ages ironing out a scene, making it perfect, and then you zoom back out and realise you don’t even need it. You’ve just wasted a week. I think I’m a little autistic about visuals. I find it hard to let go.

Could you have spent an infinite amount of time making this movie?

Yeah. I really don’t know when you would reach the point on a Star Wars movie and think, ‘Done! Finished! Nothing left to do here.’ Even George couldn’t let go. I think the originals are masterpieces, so why do you need the special editions? You did it. You achieved the Holy Grail. And yet, he doesn’t feel that way about it because they’re his babies. He was picturing something slightly better. That’s the curse of making films. It’s really hard to have feelings about them the same way you do for other people’s films, because you’re too close. We definitely aimed really high on this. But thank god there’s a release date, otherwise I’d still be there, doing it, forever.

Published 10 Dec 2016

Take an exclusive look inside our latest print issue. Available now in a galaxy near you...

In a year when big movies went bad, there are lessons to be learned from Gareth Edwards’ micro-budget marvel.