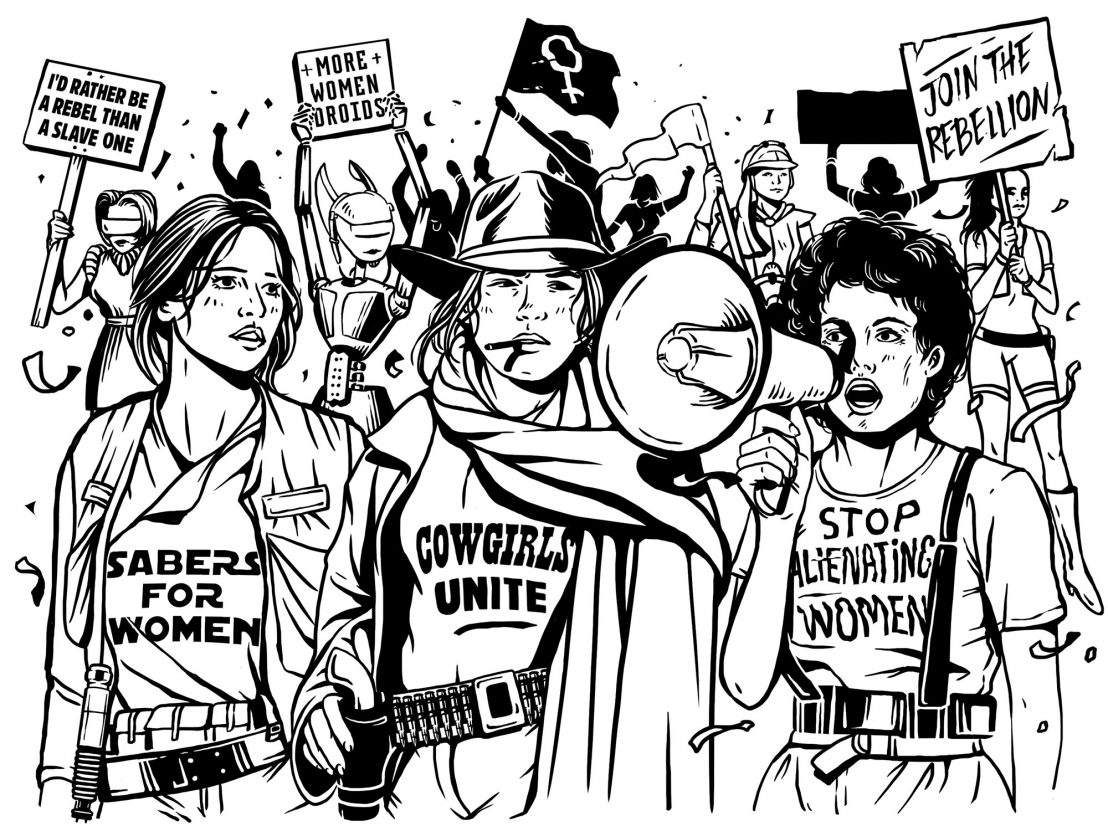

More and more movies are featuring female characters with strength, agency and a drive to take action. What took them so damn long?

Outrage from a burgeoning goon squad of men’s rights activists against major cinema releases that have dared to introduce strong, central women characters into previously dude-centric cult franchises has become so ubiquitous that it’s now an assumed part of contemporary film discourse. Mad Max: Fury Road, Ghostbusters, Star Wars: The Force Awakens, and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story have all to varying degrees sent shockwaves through these vocal communities, prompting much banging of symbolic saucepan lids from any number of social media soapboxes.

This despair seems to cluster around the question, ‘where have all the “real men” gone?’ The possibility that they may feel emasculated by the very beloved genre films of their youth seems only to add salt to the wound, prompting unambiguously misogynist tantrums that lean heavily upon the preciousness of their own subjective nostalgia. Exhibit A is that ugly old chestnut, the feminist war-cry that these reboots, sequels and re-imaginings are “raping” their childhood.

This same toxicity has recently riddled science fiction and fantasy literature as well. In 2015 and 2016, alt-right trolls took aim at the prestigious Hugo Awards and what they perceived as a leftist bias. Women, of course, have long had a forceful presence in this literary domain, particularly those driven by strong ideological motivations: Ursula Le Guin, Margaret Atwood and Octavia Butler to name but a few. And in film, directors including Kristina Buozyte, Kate Chaplin, Kathryn Bigelow, Jennifer Phang and Lizzie Borden have each used science fiction codes and conventions in profound and often diverse ways.

But it is in front of the camera that the genre’s history of strong, active women is the most visible and diverse. Heroine Maria and her evil gynoid doppelgänger in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, aggressive sex bomb Jane Fonda as the title character in Roger Vadim’s Barbarella, turbo-mum Sarah Connor from the Terminator franchise, resourceful Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games, and – of course – the iconic image of the no-shit-taking woman, Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley from the Alien movies. For starters.

But if we’re going to lift the lid off of this particular Pandora’s Box, it’s worth doing it properly. Representations of strong women in cinema bleed outwards across eras, production contexts and the often blurry lines of film genre itself. Any prehistory of women characters in the recent Star Wars movies – Rey (Daisy Ridley) from The Force Awakens and Jyn Erso (Felicity Jones) from Rogue One – must necessarily look far beyond the terrain of sci-fi itself.

These two women are important symbols, however, finding themselves on the precipice between the history leading up to their positioning at the centre of their stories, and the futures (both fictional and, in terms of real world impact, ideological) that lies ahead. These characters continue a tradition of some of the most memorable and important women-of-action in the cinema as their journeys take them on a kind of subjective, individualised process of militarisation. These are women who consciously implement an often systematic approach to Taking Action, rather than merely performing acts.

In the case of Star Wars, it would be difficult not to trace the franchise’s interest in strong women back to Princess Leia and Padmé (Leia’s ideologically klutzy slave-bikini phase aside), but it is obviously with The Force Awakens’ Rey that women moved to the frontlines of the action-and-empathy stakes. Yet Leia’s trajectory itself is telling: she does not evolve from a Princess to a Queen as regal logic would commonly dictate, but from a Princess to a General. Real princesses don’t sit back on thrones, symbolic or literal. They lock, they load, they mobilise the troops.

Acts of feminist mobilisation – be they formal or informal – are vital to women like Leia, Rey and Rogue One’s Jyn. Accusations of Rey’s Mary Sueism – a female character type whose strength is deemed too idealised, too unrealistic – fall at in the face of what was clearly years of self-training and disciplined preparation off-camera before the action of The Force Awakens played out. Her marking off days, scratched into the wall of her abandoned Walker-home, show a woman strategically preparing in wait, her dedication to up-skilling finally paying off when snowman droid-child BB-8 arrives, kicking off her intergalactic adventures.

In Rogue One, Jyn is a defiant outsider who, by joining the Rebel Alliance, underscores the symbolic power of their very name: a mobilised space where non-conformist dissidents must find a way to work together. But like The Force Awakens, the challenge for Rogue One is to find a way to continue consolidating its mythology. Juggling the franchise’s overarching narrative with its broader, iconic pop cultural potency, the trick is to keep older fans happy without becoming stagnant, either ideologically or narratively. Characters like Jyn and Rey might offer new perspectives to new audiences, but they also recall older ways of women in film rallying to action.

Even the very description of Star Wars historically as a ‘space western’ offers a potent starting place to look for the ancestors of cinema’s mobilised women-of-action. They are, on the surface at least, not difficult to find: contemporary examples might lead us to Sharon Stone’s Ellen in Sam Raimi’s The Quick and the Dead or Michelle Williams in Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff, but the reigning queen of tough western women is still Joan Crawford’s Vienna in Johnny Guitar.

Although a tough-as-nails saloonkeeper clad in masculine-styled attire, with Crawford’s signature curves and ambient sexuality, Vienna is anything but tomboyish. Surrounded by challenges on all fronts, Crawford’s steady gaze (and steadier gun) create in Vienna one of the most resilient and determined women the genre has ever offered. Yet for Vienna and so many of her western women allies, challenges result not only from the struggles inherent to life on the Frontier, but – more often than not – complications arising from gender difference, often directed at them from lovers, would-be-paramours, husbands or bastard exes.

While gender often does not rank highly on the list of concerns for women in westerns, men in these films often feel quite different. Survival therefore frequently demands they tackle how their own femininity (or lack thereof) is received by the men (and sometimes other, more orthodox women) whose stories intersect with their own. When women like these mobilise, pick up a gun, and take action, the perils of frontier living often becomes a metaphor for patriarchy itself, in all its myriad guises. Although such claims would be difficult to make for all westerns, this tendency in some is complicated further in the case of the girl-gang subgenre. Often used as a way to add some brute force sexy pizzazz to a genre whose codes are traditionally heavily masculinised.

Jonathan Kaplan’s 1994 film Bad Girls is a case in point: what had the potential to be a powerful film about feminist unity collapsed into what critic Janet Maslin memorably described at the time as a film with, “all the legitimacy of Cowpoke Barbie with a lot less entertainment value”. At the same time, the rallying of women in these contexts to band together and to fight back, to stake a claim in a cultural and social space of their own offers further evidence of the broad ways women have found to mobilise power through taking action across genre.

This becomes thornier in the case of the notorious rape-revenge film category: if there was one instance of the explicit transformation of women’s emotional and physical energy into direct political action, this would surely be it. It is therefore no surprise that rape-revenge and the western have such a long affiliation, despite the latter (erroneously) being so closely aligned with horror traditions. From The Bravados and Last Train from Gun Hill to women-driven narratives like Hannie Caulder, sexual violence and a thirst for vengeance marks many westerns.

“In terms of pure action, few women are as iconic as Pam Grier, who not only embodied the tough, mobilised, strategic woman of action, but also framed her refusal to back down as one inextricably linked to race as much as gender.”

In rape-revenge films with women protagonists more generally, gender difference and links to violence and power are key, from Meir Zarchi’s broadly despised 1978 exploitation film I Spit on Your Grave to Jonathan Demme’s Oscar-winning Jodie Foster vehicle from 1988, The Accused. What is of interest here is how sexual violence mobilises a particular kind of feminist action in the rape-avenging woman protagonist, like some kind of ideological alchemy: rape ‘turns’ women into ‘feminists’.

Girl-gang centred rape-revenge films complicate this: while more famous instances of female-avenger rape-revenge films find their protagonists isolated by their desire for vengeance, there are a number of straight-to-video, forgotten grindhouse films and TV movies examples that show women coming together, actively building feminist networks. Both these models, however, are based on women turning to mobilised, strategic action. What marks them as different from someone like Rey in particular, however, is the emphasis on their gender difference.

In terms of pure action, of course, few women are as iconic as Pam Grier, a figure who not only embodied the tough, mobilised, strategic woman of action, but also framed her refusal to back down as one inextricably linked to race as much as gender. Less well known is Cynthia Rothrock, an extraordinarily gifted martial artist who took her abilities in a range of martial disciplines to the screen, becoming a cult actor in almost 50 movies. Postfeminist ‘kick ass’ girl movies were soon to become the norm – from the feature length reboot of Charlie’s Angels to Quentin Tarantino’s revival of the trope in Kill Bill and Death Proof in particular. Tarantino regular stuntwoman-turned-actor Zoe Bell would continue to define the mobilised woman-of-action in films like 2013’s Raze, and this figure is closely linked in the broader cultural imagination to videogame adaptations like Angelina Jolie in the Tomb Raider films and Milla Jovovich in the Resident Evil franchise.

Yet these precursors to Rey and Jyn are significant as much for where they deviate as merge. While the complexity of the Bechdel Test is hardly demanding, as an ideological parlour game it certainly raises awareness of how women’s stories have traditionally been framed, their stories aligned far too often by those of the men around them. Images of the mobilised woman-of-action are diverse, and movies that address how women fit into explicit military contexts suggest that progress is not to be made by simply putting a woman in uniform and giving her a gun. The overwrought butchness of Demi Moore’s GI Jane or Goldie Hawn’s bumbling-princess-makes-good might be strong women, but are hardly the first that leap to mind.

Rather than an explicitly militarised imagination, then, Rey and Jyn suggest a turn to a type of ‘feminist corps’ motif, typified by that great forgotten icon of ’90s feminism, Tank Girl, who was played to joyful precision by Lori Petty in Rachel Talalay’s 1995 film. Kate McKinnon’s Jillian Holtzmann in the recent Ghostbusters reboot prompted a revisit to the precise kind of power Tank Girl represented, a kind of punk, post-feminist spirit of anarchy and determination. Like Rey and Jyn, these are not Action Women in the strictly generic sense, but rather something more important: they are Women Who Take Action.

This distinction lies at the core of The Force Awakens, and like it, Rogue One must find a way to maintain a sense of loyalty to the broader Star Wars mythology without collapsing into regressive, nostalgia-for-nostalgia’s sake images of women who sit around waiting to be rescued. Rey did this by staking a claim in her right to her own story, her own skills and her ability to strategise and execute her actions. That Rey is a scavenger who repurposed the visual style of the earlier films is no small coincidence: like Tank Girl on Ambien, her very habitat, her very appearance was governed by a retrospective punk feminist DIY aesthetic.

Looking back at Women Who Take Action throughout film history and forward to the role they play in the unfolding Star Wars series, women like Rey and Jyn demand we ask important questions: What can we salvage? What can we take back? What can we keep and repurpose as we move forward, and what don’t we need anymore? It seems, from this perspective, only inevitable that some conservative feathers will get ruffled. But we will keep looking – as Han Solo told Finn in The Force Awakens, “women always figure out the truth.”

Published 20 Sep 2017

By Simran Hans

A look beyond the dominant male characters that inhabit the Gone Girl director’s cinema.

Gareth Edwards opts for the slow burn over the whiz-bang in this Star Wars spin-off. The results are spectacular.

In praise of the Hong kong adrenaline junkie and architect of the time-honoured bullet ballet.