Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbour Totoro was released in Japan 30 years ago to little fanfare. Misjudged by financiers and shoehorned into a double bill with Isao Takahata’s much-anticipated Grave of the Fireflies, Totoro trod water until slowly, surely, it became one of the most beloved animated feature films of all time.

Coming into the world two days before Totoro arrived in cinemas, I find myself strangely bonded to this great grey tree-dweller. I can’t remember when it was I first saw the film, but it has always been a remedy for particularly rainy days, a trophy film presented proudly to loved ones, and the cause of many barely concealed yelps of excitement during a trip to Japan. It would seem I’m not alone, too. “It’s like a tonic,” says Paul Vickery, head of programming at the Prince Charles Cinema, a London rep cinema that has been showing Studio Ghibli strands for years. “If it’s playing on one of the days I’m working I’ll pop in to catch some of it. It just tops up the wellbeing that you need.”

This year the Prince Charles has shown My Neighbour Totoro three times already, swapping from subbed to dubbed versions in the hope of drawing in a different crowds. “When you show the film at 1pm on a Saturday to 300 people, and half of those people are children, it’s really amazing. It’s available on Blu-ray in shops nearby, yet people still bring their families to see it on the big screen.”

Perhaps one of the biggest reasons for Totoro’s success is that everyone has their own interpretation of what it means. While the physical appearance of the title character has been compared to everything from an owl to a seal to a giant mouse troll, on a metaphysical level the theories run even deeper. In Miyazaki’s book of essays ‘Starting Point: 1979-1996’, Totoro is described as a creation of Mei and Satsuki’s imagination, a gentle giant who guides them through their mother’s illness.

Some believe Totoro to be a Kami (a spirit tied to nature) belonging to the camphor tree which Mei falls into the belly of while she’s out playing. The tagline on the original Japanese poster translates as, “These strange creatures still exist in Japan. Supposedly,” which summons thoughts of old souls and endless wisdom. Ultimately, you can project whatever you want onto Totoro. Even Miyazaki leaves open the possibility that the creatures in the film don’t really exist (although he solemnly believes it to be real, as do I).

Helen McCarthy is the author of ‘Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation’ and has studied Totoro’s journey from the film’s initial release to the present day. She informs me of the short-sightedness of the film’s financiers, who hitched it onto the sure-fire success of Grave of the Fireflies, a film based on a popular short story by Akiyuki Nosaka.

Aside from Totoro making a killing in merchandise revenue, those who are familiar with Miyazaki can trace the film’s modern success to his stubborn moral mind. Reluctant to put his characters into straightforward ‘good’ and ‘evil’ boxes, the Ghibli stalwart nevertheless rewards the pure of heart and punishes greed and gluttony. It’s a trait that wasn’t missed by Roger Ebert, who described Totoro’s small kingdom as, “the world we should live in, not the one that we occupy.”

As McCarthy explains, “[Totoro] extended the studio’s positive green and social credentials by tying itself so firmly into a simpler time and a society ruled by nature. I think Miyazaki does two very difficult things in this film with considerable delicacy and grace: he makes a film at a child’s pace and on a child’s level; and he allows death to assume a major role in the movie without demonising or personalising death. It’s also consummately beautiful. After almost thirty years of watching it several times a year, it still surprises me with its capacity to deliver images of almost heart-stopping beauty.”

I love that Miyazaki is a director who is willing to roll up his sleeves and animates as well, but it’s the collaborative nature of his work that elevates it to such an extraordinary level. Totoro wouldn’t be complete without Joe Hisashi’s score, for example, a sweeping composition that is as delightful and memorable as the whiskers on the title character’s cheeks. It feels like part of the magic that makes Totoro take flight or gives the cat bus its 12 legs.

Sega Bodega is a music producer and performer who has sampled Hisashi’s work in the first of three shows dedicated to the music of Studio Ghibli for a special run on NTS. For him, the score is an unmatched mix of playfulness and grandeur: “It’s the choice of sounds that makes it so heart-warming. It’s all very fun; cartoon-type noises but in parallel with this melody and chord progression that kills me.”

Bodega listened to every score from Studio Ghibli for the series but rates the originality of Hisashi’s score above all others, which links directly to his appreciation of the film. “There is just such a purity to it, but like a mature one. So many times, I go back to films I watched as a kid and find that they’re shit. But Ghibli films feel like coming of age films, mixed with pure fantasy. It just seems like a timeless combination.”

Timeless is key here, because the power of Totoro seems infinite. “You will never see an audience as happy as the one leaving the building after we screen Totoro,” adds Vickery. “A lot can be said for going to see a film that is genuinely just very nice, and you leave the screen with a big smile on your face because it doesn’t happen that much. You leave feeling full of love almost.”

Published 15 Apr 2018

By Amy Bowker

The animation house has unveiled plans to build a theme park on the Aichi expo site.

By Jack Godwin

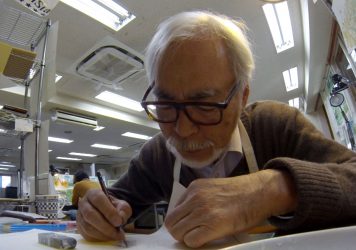

Never-Ending Man offers rare insight into the Studio Ghibli co-founder’s creative process.

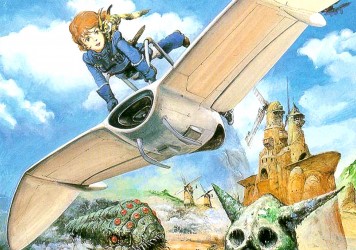

Gorgeous original artwork spanning three decades of the iconic animation studio.