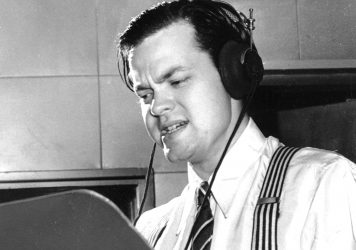

Mark Cousins returns with an essay feature on the doodles and draftsmanship of Orson Welles.

Published 15 Aug 2018

Mark Cousins locks horns with one of the titans of cinema.

A very personal (too personal?) journey through the films of Orson Welles.

The incredible material helps the film take flight. Bring on the major gallery exhibition.

The Lady from Shanghai is a prime example of the legendary filmmaker’s complicated genius.

The itinerant and inquisitive cinephile delivers this moving child-based addendum to his mammoth The Story of Film.

A passible Welles hagiography which offers very little that you won’t easily find in an Encyclopedia.