Scorsese’s monolithic passion project finally arrives, and it’s a ripped straight from his spiritually devout heart.

A 1966 novel by Japanese Catholic writer Shusako Endo has obsessed Martin Scorsese for so long that Silence ends a three-decade slog to bring it to the screen. Scorsese’s reputation has long been assured, and while the past decade has brought the likes of The Aviator, The Departed and The Wolf of Wall Street winning new audiences and sustaining his commercial viability, none of them have seemed wrenched from his soul in the way that, say, Taxi Driver or Raging Bull so evidently were. Might this 159-minute historical saga about a Portuguese missionary in 17th-century Japan be the late masterpiece to at last reveal the true Marty?

Well, you certainly get the sense that’s precisely what he’s set out to do. It’s essentially a story about a super-keen young priest named Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield, positively quivering with sincerity), whose faith is tested when searching for his old mentor (a suitably careworn Liam Neeson), the latter believed to have renounced his religion under torture after the previously welcoming Japanese authorities have decided to cauterise all traces of Christianity from their country.

Rodrigues’ very presence, however, will expose the underground local faithful to fiendish punishment, sending him into a vortex of doubt as native innocents die horribly for their beliefs. The title then, refers to the silence of God in the face of human suffering – a heavy-duty theme met with heavy-duty celluloid treatment. Brows are furrowed, the pace is painstaking, the direction highly reserved by Scorsese standards.

Who knows when anything this austere last hit the multiplexes, since we’re in the classic arthouse territory of Robert Bresson and Carl Dreyer, working a low-key naturalism imbued with a would-be spiritual aura. The expansive running time is a slow build, but its sheer depth of feeling brings a gradually enfolding embrace, pressuring us to confront fundamental questions about the nature and value of religious belief.

Of all people, it’s Shinya Tsukamoto (erstwhile director of out-there horror fare like Tetsuo), whose heartbreaking performance as a humble peasant aflame with Christian fortitude hits home early, prelude to an extended theological battle of wills between Issey Ogata’s wily magistrate and Garfield’s Jesuit cleric, whose yearning for the glory of martyrdom is looking increasingly shaky.

It’s cumulatively involving, but not everyone will side with Scorsese’s take on apostasy (publicly renouncing Christianity) as a soul-deep betrayal, since keeping the faith is only unleashing misery on the believers. Moreover, while the low-key visualisation carries a certain monolithic weight, there’s a slight lack of poetry to give the film its own spiritual lift-off. Unlike Endo’s vivd novel, here we’re basically held exterior to Garfield’s inner ferment, leaving a good actor striving against near-impossible circumstances.

For all that, Scorsese’s sheer seriousness of address is itself an act of faith in cinema’s ability to confront the most esoteric of issues, though strangely the film’s most affecting moment comes with the end credits, scored to the sound collage of a storm breaking at sea, which at last epitomises the buffeted serenity this very personal odyssey has been seeking all along.

Published 1 Jan 2017

Scorsese’s dream project, so this time it’s personal – a late masterpiece?

A 159-minute slow burn which will probably resonate more deeply with the Catholic faithful.

That a film this daringly austere exists in the marketplace is almost miraculous in itself.

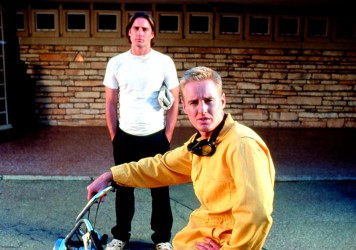

Wes Anderson’s brilliant debut, which turns 20 this month, channels the youthful spirit of Mean Streets.

LWLies talks to the actor whose star is currently in swift and unstoppable ascent.

By Paul Risker

With Martin Scorsese’s seminal crime drama finally out on Blu-ray, we gauge the film’s enduring influence.