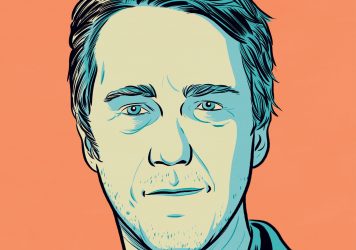

Edward Norton directs and stars in this patchwork New York noir about a Tourette-suffering private eye.

There’s an astonishing scene in Motherless Brooklyn where Edward Norton’s gumshoe narrator, who has Tourette syndrome, chases a lead in the case he’s working to a small, smoke-filled jazz club in Harlem. Pulling up a stool at the far end of the bar next to the cramped back-corner stage, he begins to twitch and scat in serendipitous harmony with the music, his every tic and yip matching the house band’s off-beat groove. For the first time in his life, Lionel Essrog’s neurological affliction suddenly makes sense.

If only the same could be said of the film itself. Adapting Jonathan Lethem’s 1999 novel of the same name, this is Norton’s second directorial effort after 2000’s Nora Ephron-lite love triangle comedy Keeping the Faith. Having also taken on the lead role and screenwriting duties, his long overdue follow-up has the distinct air of a vanity project doomed by its maker’s overambition. To be fair to Norton, with so many disparate moving parts and so many weighty themes at work, it’s a wonder he’s managed to deliver something even remotely coherent.

Just as Essrog is not your average private dick, Motherless Brooklyn is a less-than-conventional postmodern crime noir whose central murder plot (nice to see Bruce Willis earning his keep for a change) is essentially window dressing for a stern-faced examination of New York City’s murky municipal past. Specifically, the film addresses the systematic dismantling of inner-city communities during America’s postwar boom years, taking a particularly dim view of the men who ruthlessly exploited the poorest and most vulnerable citizens under the banner of ‘progress’.

Following a mysterious paper trail in the wake of his boss’ death, our hero eventually finds his way into the marble-decked offices of Moses Randolph (Alec Baldwin), who displays all the bluff and bluster of a career politician but is in fact an unelected public official with grand designs on remodelling New York regardless of the cost (monetary or otherwise) to the local taxpayer.

Randolph is a barely-disguised proxy for Robert Moses, the powerful town planner whose urban renewal project saw scores of working-class people – mostly black and ethnic minority – displaced from their homes throughout the 1940s and ’50s. (For more on this subject, seek out Robert Caro’s excellent 1974 biography of Moses, ‘The Power Broker’.)

Fascinating though it is to see Norton continue Caro’s work in scrutinising the legacy of one of Gotham’s most influential and controversial figures, Norton’s anti-capitalist message is undermined by his film’s sentimental tendencies. Even if you can stomach the romantic subplot between Essrog and Gugu Mbatha-Raw’s community activist – soundtracked by a maudlin ballad performed by, of all duos, Thom Yorke and Flea – and a still more baffling family reunion subplot involving Willem Dafoe’s crotchety loner, you may well find yourself distracted by Norton’s full-tilt performance.

This film wants us to come away thinking about the unjust and racist foundations upon which the American Dream was built, but instead it’s the image of Norton ski-do-be-bop-bapping in that smoky jazz club that lingers.

Published 2 Dec 2019

Like Edward Norton, actor. Less certain about Edward Norton, director.

A hot mess, but in a fun way.

Capitalism: bad. Racism: bad. Jazz: bad??

Oscar Isaac delivers the goods as the pacifist hero in this strange and slightly unsatisfying period crime drama.

The writer, director and star of Motherless Brooklyn talks New York, noir and making musical acquaintances.

The Good Time directors reveal the secret to capturing the essence of their home town on screen.