Martin Scorsese’s wistful remembrance of tragedies that befell the Osage nation is a film of high seriousness and low spectacle.

In Martin Scorsese’s 2002 film Gangs of New York, America was born on the streets. In his new one, Killers of the Flower Moon, it dies a slow death out there on the prairie. With bracing echoes to contemporary political malaise, it’s a chronicle of early 20th century midwestern history that draws on Hannah Arendt’s concept of the “banality of evil”, in that it depicts the everyday genocidal tendencies beholden of Prohibition-era white prospectors of all economic stripes. In this film the crucible of modern civilisation is framed as little more than a gamified kill floor for the afflicted and rapacious.

It is, in a strange way, a rueful, elegiac sister film to 2010’s lude-powered bacchanal, The Wolf of Wall Street, in that it offers a stinging critique of capitalist exploitation that’s operating at a sociopathic level, where the expenditure of human suffering most certainly justifies any long-game dividends, and the prescription meds are swapped out for moonshine.

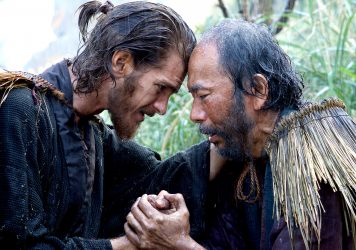

And in this case, the perpetrators are happy to look their victims in the eye and tell them they love them before pulling the trigger or administering the poison. Leonardo DiCaprio even plays a proto-Jordan Belfort type who constantly exclaims how much he “loves money”. In terms of tone, however, it’s more of a piece with Kundun or Silence.

It is drawn from the pages of the disquieting non-fiction best seller by New Yorker stringer David Gran by Scorsese and screenwriting veteran Eric Roth, and the story takes place in Osage County, Oklahoma – a place where you’re more likely to be arrested for “kicking a dog than you are shooting an Indian.”

Land ceded to and consecrated by the Osage nation is revealed in a somewhat hokey opening scene as being literally bursting with oil. The members of the Osage then suddenly became some of the richest people on the planet, and it wan’t long before a complex apparatus of malicious white profiteering was constructed alongside the waltzing oil derricks that littered the horizon.

Bespectacled tyrant “King” William Hale (Robert De Niro) employed philanthropy and superficial civic benevolence as a smokescreen for a reign of terror in which he engineered the murder of scads of Osage with the aim of eventually inheriting the “head rights” for their oil wealth. He brings his greasy, malleable nephew Ernest Buckhart (DiCaprio) into the fold, sending him forward as a vital pawn in his complex game.

Lily Gladstone’s Mollie Kyle becomes the locus for Osage disenchantment, accepting Ernest’s semi-sincere hand in marriage while the corpses of kith and kin are being discovered with alarming regularity, and not rousing so much as a raised eyebrow from bought-and-paid-for local law enforcement. The gradual diminution of the strength and confidence she exudes in the film’s opening stretch transforms her from avenging angel to passive victim, and her psychological non-presence in the story’s second half does the film few dramatic favours.

While Killers of the Flower Moon is obviously the product of America’s foremost cinematic artisan, the film itself never quite dovetails with its maker’s vaulting and urgent moral ambitions. Unlike in the director’s delicious crime epics of yore, we are not being asked to bask in the eroticised immorality of the bad dudes. Instead, the decision has been made – a completely laudable one – to shift the framing to a more objective vantage, one that centres the struggles of the Osage, while slightly downplaying the nefariousness of the antagonists, and almost entirely omits the perspective of the eventual FBI investigation.

Indeed, with stories of the film’s protracted editing period, one imagines a floor piled up with excised footage of Jesse Plemons’ softly spoken G-man, Tom White, who is arguably the main focus in Gran’s book, and who doesn’t enter stage right until well beyond the film’s two-hour mark. Nevertheless, much like John Ford 1964 epic, Cheyenne Autumn, a sweeping and cinematic corrective to formative depictions of America’s Native communities, Killer’s of the Flower Moon is Scorsese’s way of giving ownership of this tragic narrative – as much as he is able to – back to the victims.

Scorsese is also deeply invested in the notion of lost history, of the precariousness of collective memory and the malign manipulation of public record. He emulates newsreels and photographs throughout the film, constantly reminding how official histories are struck by the commercial image-makers, and the novelty of the medium at that time meant that it was rare not to see people smiling and apparently happy with their lot.

It’s a wistful epic that downplays frivolous dramatic beats and guts the story of anything that might sully the high seriousness of the subject matter. We know who all the characters are and are certain of their motivations within the film’s opening minutes. It means that the film plays more like vignette-driven history than a rich, powerfully-structured drama. Empty-calorie spectacle, in this instance, is very low on the agenda.

Of course, every actor gives the director their all, with DiCaprio making for a charmingly tragic presence as squirming Ne’er-do-well, Ernest Burkhart. Gladstone, meanwhile radiates stoic indigence, while De Niro delivers some of his most committed and detailed screen work in years, channeling (and even directly referencing) his Al Capone from The Untouchables – albeit with a paddle rather than a baseball bat.

Things end on a high in the form of an extraordinary coda which is pure Scorsese. It both laments and praises the fact that history is often just grist to the mill of mass entertainment, framing the stories that we have just seen as merely dust in the wind. This is on first impression perhaps a very good, uneven film rather than an unequivocally great one.

Little White Lies is committed to championing great movies and the talented people who make them.

Published 17 Oct 2023

When Marty calls, we answer.

A big, fascinating, frustrating, slightly lopsided, sporadically brilliant prestige epic.

On first watch, maybe not vintage-level Scorsese. But boy, I can’t wait for round two with this one.

A de-aged Robert De Niro takes centre stage in Martin Scorsese’s muscular, melancholy mob drama.

Scorsese’s monolithic passion project finally arrives, and it’s a ripped straight from his spiritually devout heart.

By Calum Marsh

A late-career dirty bomb from Martin Scorsese in this licentious and hilarious essay on greed and excess.