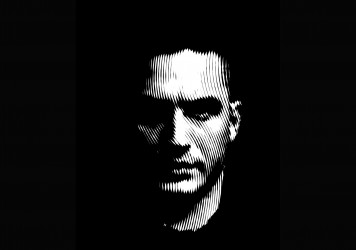

Tom Hardy delivers a knockout performance as Britain’s most notorious convict in this bruising psychodrama.

“You’re a very sweet man, Charlie,” says Irene (Kelly Adams), “but you’ve got no ambition.” It’s hard to know whether to agree or disagree, for Charlie (Tom Hardy) may be blessed with a roguish grin and a charismatic naïveté, but he is also ‘Britain’s most violent prisoner’, a pugnacious powder keg of a con who seizes any opportunity to brawl with the screws. As for ambition, he has that in spades, but it is ambition of a kind that, in keeping with these celebrity-obsessed times, never seems to get beyond merely wanting to be famous.

Charlie finds the path to this ‘calling’ in prison, where his aggression soon wins him the recognition he has been craving – and so he invents for himself a particular persona as a hardman, adopting the ‘fighting name’ of Charles Bronson (he was born Michael Peterson), and repeatedly engineering incidents that bring him into unwinnable conflicts with his captors.

There have been many films about the prison experience, but Nicolas Winding Refn’s mannered biopic is the first to examine its incarcerated subject not as a monster or a victim, but rather as an artist – and one who truly suffers for his art, whether through regular beatings or long stints in solitary.

Ever mindful of his image and its management, Charlie is allowed to fashion his own story, either in ‘raw’ addresses to camera, or in full clown’s make-up on an imagined stage before an applauding, tuxedoed audience. That this fractured narration of events, with all its camp bit-players and surreal flourishes, is itself cast as just another piece of showmanship merely underlines the elusiveness of the ‘real’ Charlie, a man masked by an actor’s name (and played by yet another actor). Hardy’s Bronson is always, as he puts it, ‘making a name’ for himself, but isn’t so clear on the question of ‘what as?’ And so, asked repeatedly by the prison warden what it is that he wants, Charlie seems unable (or at least unwilling) to answer.

It becomes increasingly clear, however, that the performance itself is what constitutes the man, and our attention is all that is needed to sustain him. Without that, Charlie is just another battered and bruised figure alone in a cage. Still, in a film closer to A Clockwork Orange or Blue Velvet than to Chopper, brutal ultraviolence and art-house oddity make for an arresting mix, while it is impossible to take your eyes off Hardy’s intense serio-comic turn.

Published 12 Mar 2009

Hasn’t Chopper already covered clownish violence behind bars?

Well, yes, but this is nothing like Chopper.

Irredeemable thug or unconventional performance artist? Bronson is hard-hitting either way.

LWLies goes nose-to-nose with the UK’s most fearsome acting talent and lives to tell the tale.

With The Neon Demon the Danish writer/director has made his most provocative film yet. We travelled to Copenhagen to meet him.