Drone strikes, exploding whales and a Portugal on the brink of collapse... Miguel Gomes’ astonishing latest is a new breed of movie epic.

Hands up who remembers Woody Guthrie? Perhaps you’ve tapped a cuban heel along to his rousing folk standard, ‘This Land Is Your Land’? Or maybe you caught Hal Ashby’s 1976 film adaptation of his memoir, ‘Bound For Glory’, in which the nomadic troubadour penned songs inspired by the hardships he saw in Dustbowl America? He was a man who created rough-hewn, but humanist art. It transcended mere entertainment and became folkloric social history, a vital chronicle of a time, a place and a way of life.

There has always been an inkling that Portuguese film director and occasional dandy, Miguel Gomes, styles himself as a modern-day Woody Guthrie, a cine-outlaw riding the rails and filching from reality to feed his fictional fantasias. He, however, is more prone to playful irony than earnestness, even though his aim always remains true. His first great film, 2008’s Our Beloved Month of August, contained a moment where he offered viewers the sensation of passing through the looking glass from the comforting land of reality into the fictional realm of celluloid dreams. This film – coincidentally about the tradition of folk music in rural Portugal – highlighted this notion of drawing energy and ideas from the land and from history. The film tries to pinpoint the moment where fact becomes legend, where prosaic events and have-a-go heroes are preserved in the shimmering amber of creative endeavour.

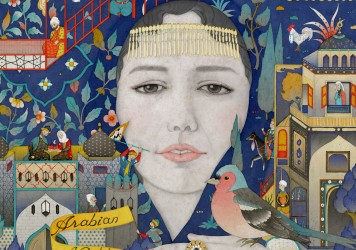

At the beginning of his awesome new three-part feature, Arabian Nights, the director appears wearing a raincoat, sitting on some garden furniture at a hotel. His downbeat, confessional narration forewarns that, with this film, he feels as if he’s about to embark on a fool’s errand. The story goes that he was in a shop with his daughter and she asked for a toy. When Gomes said no, she responded: “Is it because of the austerity measures?” The fact that even his daughter knew about Portugal’s slump into poverty was the eureka moment he needed to build a triptych of films – a folly of rare magnificence – which exist as a fleeting survey of a country in dire straits. Like the phantom crocodile at the beginning of Gomes’ 2012 masterpiece, Tabu, this is a sad and melancholic film, though it is not a maudlin one. Its content oscillates between the absurd and the arcane, focusing as much on minor-scale rebellion as it does on the bittersweet decimation of a rich cultural heritage.

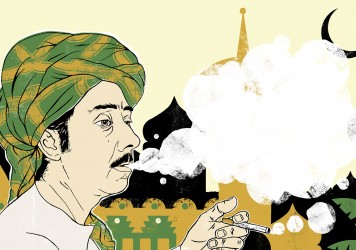

The film is so-called because of its loose allegiance to the canonical Arabian tome, ‘The One Thousand and One Nights’. Yet Gomes takes pains to assure us at the beginning of each chapter that only its structure inspired his film. In the book, virgin waif Scheherazade (Crista Alfaiate) uses her skills as a virtuoso raconteur to keep the murderous king from ravishing her and putting her to the sword. She tells him stories about his empire, about survival and custom, about magic and adventure.

In this spirit, Gomes casts himself as Scheherazade, while the contemporary politicians and power brokers wreaking havoc on the land are the demonic king. These stories are entertainment, but in such situations, they are also a tonic for widespread misery. As he deals so directly with “the now”, there’s a reactive feel to the vignettes Gomes weaves, where form is almost a natural byproduct of each new subject. First it’s a documentary, then it’s fiction, then the two worlds collide and all bets are off.

A scene-setting sketch from the first film – The Restless One – sees a gaggle of hard-nosed ministers squabbling over Portugal’s national debt repayments in a rural taverna. It is framed as grotesque satire, like a ‘Charlie Hebdo’ cartoon writ large. A wandering soothsayer casts a spell which gives the men bulging erections, and with this libidinous charge, they suddenly become more sympathetic towards the country’s economic restructuring. The absurdist tenor of this opening gambit is crucial — it places this most serious of bureaucratic decisions neatly alongside the more fanciful anecdotes to come. It also expresses Gomes’ belief that stories can still retain their essence and emotion however much you accentuate their whimsical cock-and-bull nature.

The second film – subtitled The Desolate One – opens with another important tale: The Chronicle of the Escape of Simão ‘Without Bowels’. It stars sinewy oldster Chico Chapas as on-the-lam murderer Simão, his anatomical nickname the result of his having a healthy appetite but never gaining weight. Gomes unapologetically sides with the daydreaming killer, along with the local populous who are invigorated by this ageing fugitive, who outsmarts the drone technology and bombastic firepower wielded by state oppressors. The film as a whole looks at how momentous political settlements have unknowable human ramifications, but also how they can subvert a basic sense of right and wrong. The dashing antihero is a staple of romantic cinema – but here, that fictional archetype has blazed a path into stark reality.

Gomes applies the reactive impulses of a documentarian with the florid imagination of a fabulist. The element of his films which is at once the most impressive and potentially the most alienating is the way he views time and space as mutable, sometimes opting to have various historical eras existing in the same moment, in the same frame. Mixing timeframes is often a source of mirth — as with the roving peasant in the beginning of the third film who attempts to seduce Scheherazade with his breakdancing prowess. But this off-hand comic displacement is a red herring. For Gomes, history is cyclical and the eccentric travails of man tell a universal narrative.

The film’s final chapter – dubbed The Enchanted One – is also its most beautiful and moving. While the second chapter is the most openly outraged, focusing on destitution leading to crime and death (happiness can only be achieved if you are a cute dog, apparently), part three at once ties up everything that has come before it. It offers a pure expression of how humans instinctively muddle through times of woe. The Inebriating Chorus of the Chaffinches transports us deep into the captivating world of competitive chaffinch song tournaments, where jobless men fixate on the repetitive, three-tier warble of their captured specimens. Chico Chapas returns, no longer as Simão ‘Without Bowels’, but as himself (or so we’re led to believe), an expert chaffinch trapper whose skills help many become part of this delicate sub-culture.

While Gomes is methodical in presenting the various key characters on the chaffinch song “scene”, it’s not just so he can parlay them into some kind of reality-style competition set-up. This is about homespun culture erupting through the cracks of depression and the irrepressible nature of poetry. While it may outline the extent of the suffering caused by austerity measures, Arabian Nights offers an extravagant expression of optimism in the face of civic desolation. It shows people enraptured by their surroundings, and sometimes not even realising it. Gomes keeps his righteous anger in check, but he also refines his sense of revelry.

The film climaxes on a school choir singing ‘Calling Occupants (of Interplanetary Craft)’, made famous by The Carpenters to celebrate World Contact Day – an occasion where we might one day reach out to alien lifeforms. Chapas is filmed striding down a country lane having just helped a wind sprite trapped in a chaffinch net. Is it a happy ending? Is Chapas moving forward, triumphant, contented, at peace with the world? Or is he striding headlong into an abyss of unimaginable sorrow? We dream of blissful escape and of exotic lands as a way to fulfil idle pleasures. But movies are those dreams. They are enablers of the fantastic. Maybe this capricious cross-cut of a society in the process of a bitterly poetic transition is the time capsule that Gomes wants to blast into space for the aliens to see. There can be no doubt that its humour, empathy and strange ingenuity would make them want to pay us a visit.

Arabian Nights Volume One is released 22 April, with Vols 2 & 3 out 29 April and 6 May.

Published 21 Apr 2016

Gomes’ previous, Tabu, is one of this decade’s finest thus far. So yes, excited is the word.

A freeform mélange of styles and themes that comes together in stunning fashion.

A glowing lovesong to Portugal performed by a man who has mastered a range of exotic instruments.

The Portuguese writer/director on his wondrous three-part epic Arabian Nights.

This sublime Portuguese fantasia from director Miguel Gomes will likely feature heavily on best of year lists.

Enter the magical, mysterious world of Portuguese director Miguel Gomes’ three-part masterpiece.