The screen icon speaks candidly about her remarkable career, and her complicated relationship with the late Swedish master.

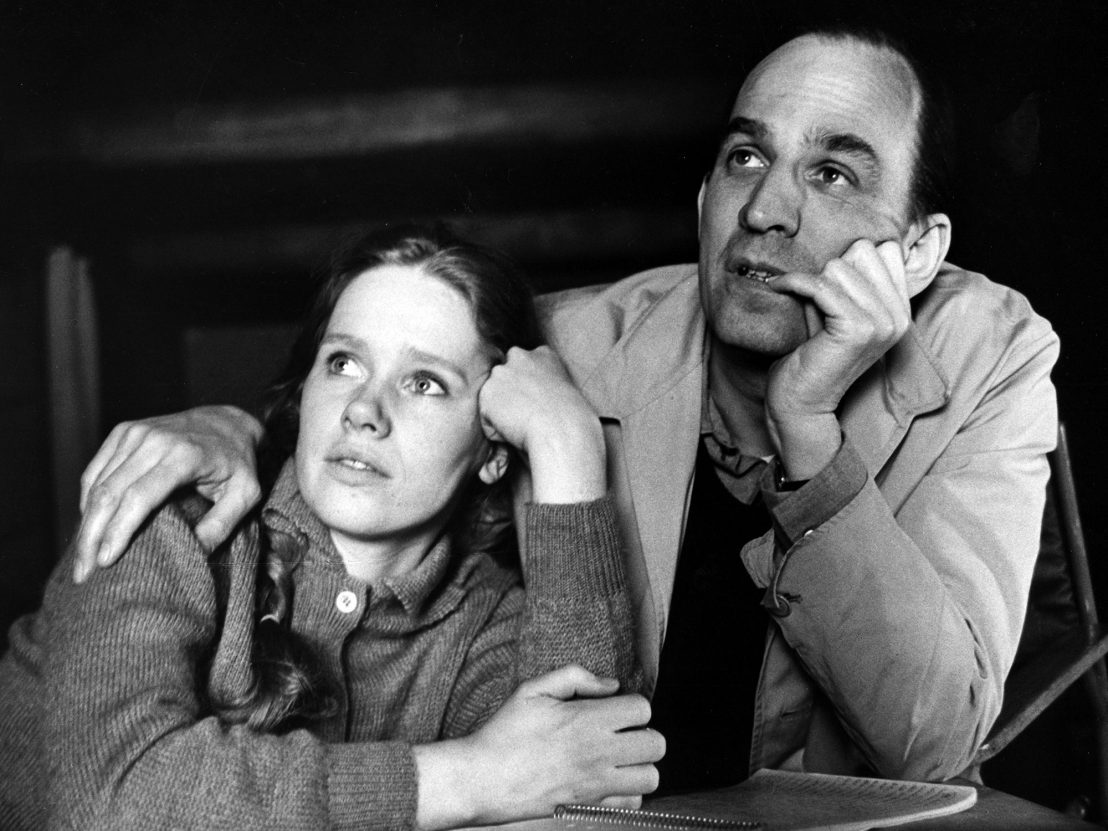

Having starred in 10 of his films and directed two of his screenplays, the career of Norwegian actor Liv Ullmann is indelibly synonymous with the films of Ingmar Bergman. His lover and muse for what was arguably his greatest run of films, Ullmann first worked with the Swedish maestro on his island home of Farö in 1966.

The resulting film, Persona, might just be his crowning achievement, but theirs was a working relationship that lasted long after the romance kindled that summer ended, right up to his final film in 2003. With a complete, three month retrospective of Bergman’s cinema currently underway at London’s BFI Southbank, in his centenary year, we sat down with one of the greatest living actors in world cinema to discusses their fruitful yet complicated kinship.

LWLies: You must have been interviewed about your time with Bergman hundreds of times over the years.

Ullmann: I really don’t mind because sometimes you do hear new things. It helps me to continue to understand what wonderful luggage he gave me, especially now that I’m starting to look more at his writing than his movies. I’m finding this new Bergman who shouldn’t be new for me, but still is. Just this incredible writing and recognition of people. Even when I’m being interviewed about something that has nothing to do with Bergman, it always seems to come back to him. I did complain about that to him, and he said those famous words, ‘You are my Stradivarius!’

What have you found to be the most common misconceptions through the years about your professional and personal relationship?

I wouldn’t know about misconceptions, but I’m sure there are many. I’m often asked how I feel about having to talk for him, but I feel I’m a very natural person to do that. When he was alive and used to cancel engagements at the very last minute, it was always me that ended up going there. He really didn’t mind because I worked so closely with him as a director and as an actor, and because I knew him so well as a friend and, for some years, as a lover. When you know someone as a lover, you get to know things about the person that others don’t know. So I like doing it.

When it comes to him, he liked to follow what I did. With Bibi Andersson and Harriet Andersson – these incredible geniuses that he worked with – he did not like it when they went abroad. Even if they did good things. He said to Max von Sydow, ‘Max, why are you ruining your career?’ But for some reason he liked when I did it. I think he recognised the same shyness in meeting people that he felt himself. He would get so excited, travelling to New York for just one night when I was on stage there, happy for me to do the things he perhaps wished he could do too.

Has your memory of that time been affected by the telling of it over 50-odd years? You said once that you have to be selective with your memories…

When did I say that?

In an interview a few years back.

I think that was because my daughter came out with a book. She’s a wonderful writer, but she’s very selective in her memories of her childhood. At first I was very upset about it, but her memories are not my memories. My memories are also selective in the way I would like things to be and the way they probably were. Also, the way they never were. Maybe I should say that too because that would explain more about my feelings.

In your second memoir, Choices, you write about a lover describing your time with Bergman to you, describing your own experience to you. He called you a ‘fairy tale princess locked in a castle.’ It must be a strange feeling, having a lived experience romanticised or mythologised by other people who weren’t a part of it.

I think we have a tendency to do that ourselves, not only to be able to write about it, but to be able to live with those memories. Writing is about getting your soul down on paper, and once it’s there, it really is you because it comes from your soul. That’s what Ingmar really believed in, that if you can get it down on paper, then on film, that film comes closer to your soul than, for example, you and I talking now. It has recognition from the souls of the audience. I didn’t always see how incredible he was as a writer until I started to work with his writing myself, as a director. It wasn’t until I adapted Private Confessions for the stage that I realised how good the writing was, even after having already made the film.

I don’t even know what our relationship is any more. It was 45 years ago that we were romantically involved, but I do know that it was against everything that I thought I knew was right. I got divorced, I had a child out of wedlock, my Christian family didn’t want to see me any more. I was on this island that was his safety but didn’t really feel like mine. But I also knew incredible times where I’d never felt so safe, and so real, looking into someone’s eyes and knowing that I was recognised. Not just that he recognised me, but that when we looked into each other’s eyes, he knew that he was recognised too.

I knew that whatever happened to us, even when I left and knew I wasn’t coming back, that it would be for the rest of my life. I do feel that the friendship we kept, that was there until he died, was built on a romance that was probably different to how I remember it now. I see pictures that I have no memory of being taken, where I’m asleep in a chair and he just passes by and softly touches me. I know that we really were entwined. Obviously other people could say the same, but it doesn’t cut into mine.

Dheeraj Akolkar’s 2012 documentary, Liv & Ingmar, cuts together sequences from the films with your recollections of that time. It makes the films appear explicitly autobiographical. Do you see them the same way?

I really like that movie, and I like the young director, but I do not agree with people hearing my story and seeing the violence [from Scenes from a Marriage]. Ingmar was not violent. He had a lot of stuff, I’m sure, but he was not violent. I didn’t understand how it could look like that until I saw the finished movie. The violence is happening within you, and it’s awful, but there’s no kicking and screaming.

When you hate someone, your anger or your dissatisfaction with that person is far worse than the violence of someone kicking you. It’s so horrible because it’s so difficult to get rid of. The strange thing about this movie is that whenever I’m travelling with a film, audiences always ask about Ingmar. With this one, an incredible thing happened. No one got up and asked about Ingmar, no one got up and asked about me. They all got up and talked about themselves. Even with all that violence that looks like it could be Ingmar and me, it opened up something in them and they talked about themselves.

Reading your two memoirs, the way you write about the end of your relationship with both Ingmar and the later lover really brought to mind the ending of A Doll’s House. It’s clearly a play that’s meant a lot to you through the years. Were there ever any plans to film it?

I had the film. I had a great script. I had Cate Blanchett for more than a year, and we had American money. Then she couldn’t do it because she was having a baby, so I had Kate Winslet who stayed with it for almost two years. I had all the locations, but in the end I just got really angry that it was going in so many different directions, so I just jumped off.

Could it ever come back?

I don’t think I’ll ever direct again. I love working with actors, I really do, but it’s tough to be a woman director. It’s tough to be my age and a woman director. Not with the actors but with the technical people. With the line producer, with the cinematographer. No, I’ve decided I won’t do that.

The play has real political resonance now especially. It’s sad to think that it was written some 140 years ago and so little has changed.

It’s another reason why I don’t want to direct again. I have to dance around. Not dancing in and out of hotel rooms, but dancing around to satisfy men so they don’t get angry. As a woman, I think I have to try to be nice and pleasant to get respect from men. Otherwise, I might get angry and ruin it for myself. I was brought up to be old-fashioned, and then came women’s liberation. My generation was in the middle, and a lot of wonderful women are happy to stay there. I try so hard not to dance, but I still dance. It’s important for me to say that a lot of women are so horribly treated in different African countries. It’s easy to forget that it’s not just us privileged women that have been abused, there are so many more in much poorer countries that undergo daily abuse for their family’s survival. I think it needs to be more on the agenda than it is.

You have a longstanding relationship with Haiti especially. The comments from the man in charge about “shithole” countries last week must have hurt.

The man in charge is filling everyone with such hate. Even going on an airplane, it feels like everyone is much more aggressive. You can’t talk with such hate without it affecting a country sooner or later. Of course it hurts inside the United States, but it hurts the people he’s talking about a lot more. It’s really scary, this message of hate he’s sending.

The Emigrants should be mandatory viewing for his administration.

Well yeah, especially now that’s he’s so into Norway. Actually, that was Swedish, but still. We’ve talked about anger in Ingmar’s films and that documentary, but Mr Trump’s anger is just anger at people and frustration at who he is himself.

There’s a line that Bergman wrote for Hour of the Wolf that goes, “When a woman lives long enough with a man, she becomes like him.” Do you agree with that? In what ways did you and Bergman become like each other?

I think we were alike, which is very strange because we were also so different. He’s never acknowledged this, but I never took parts from Harriet or Bibi. I was him. Not in Scenes from a Marriage, perhaps, but I was very much him. We were twin souls. It was the safety of a hand. We always ended our letters with, ‘My Hand.’ We both had a grandmother that we loved dearly. Ingmar’s used to take him to these incredible wonderlands, and he’d describe them to me in the evenings. He always said, ‘My whole life was about trying to get back to those wonderlands that my grandmother would tell me about.’ That’s what he did. That’s what his images are about, images that you’ll never forget.

Your characters always feel so deeply inhabited. Do you find it easy letting them go? Do you ever think about their lives once you’ve left them?

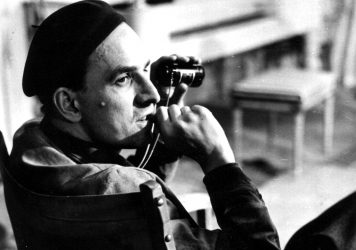

They were never hard to let go because they were just characters. Ingmar would never explain what they were about or jump into your fantasy. You’d read the script, then you’d create something and he’d say, ‘Little more, little less.’ What I do remember are magical moments where he didn’t say very much. I remember a scene where I had to commit suicide and him just watching. The only thing I heard him say to someone was, ‘You did remember to switch the pills for sugar pills?’ He knew what he did, but it added to the tension when the camera was rolling having that in my mind. It was exciting!

Was there ever any conflict between his idea of a character while he was writing and your interpretation, or was he completely open to whatever you’d give?

No, he wouldn’t allow a different interpretation, but I didn’t have those conflicts with him somehow. He knew who he was writing for. The only time I really experienced it was with Ingrid Bergman, and that was pretty tough. They hated each other on Autumn Sonata. I had this three page monologue of all the awful things she’d done to me as a mother. Incredible lines. Obviously, I had some idea of how to do it, as an actress. I had to do all my lines first while she just stood there, taking it. I did it, and it came out pretty good, but Ingrid was shocked, even though the camera wasn’t on her.

When it turned around, she said, ‘I’m not going to do that. I’m not going to say those lines. I want to smack her.’ She screamed, and he screamed, and they screamed at each other. They went out to the corridor and screamed some more, and we thought, ‘The movie’s over!’ That’s when you protest. They were his lines, and they had to be his lines. Finally they came in, genius and actress, genius having won. She did the scene, but if you look at her face, that hatred – at having to say the lines – is real. No wonder she was nominated for an Oscar. He loved it. It wasn’t what he wanted, but it was what he got, and was better than he’d imagined.

He trusted his words, and that’s what was exciting. If you’re having a conversation with someone, and you’re expecting an certain answer said a certain way, it’s no fun. It’s more exciting to say ‘I love you’ to someone when you don’t know know what the answer back will be. Ingmar would never say, ‘Your interpretation was wrong.’ You don’t give an interpretation, you give from the heart.

Ibsen wasn’t quite so lucky. He was told to change the entire ending of A Doll’s House when his actress complained…

And he did it! But Ingmar never changed a word. Truth is whoever is saying it, and he knew that. My biggest mistake in my life was turning down Fanny and Alexander. I said no because he told me it was a comedy. Max did the same. He re-wrote my part, which was probably the best part I could have had from him. For almost a year while he was shooting and editing the movie, it was the first and only time we were not friends. He wrote me letters calling me “Miss Ullmann.” It was terrible. He asked me to come and see it when it was finished, and I sat at his side crying and crying. I heard from the Stockholm Archive that in his manuscript from that time, he’d written in several places, “I’m so angry at you Liv!”

I’ve always thought of you as one of cinema’s great listeners. Some of the strongest moments in the Bergman films come from you just listening. At the piano in Autumn Sonata. When Erland Josephson tells you of his affair in Scenes From a Marriage. That incredible shot in Passion of Anna. You write in your book about not using your own personal memories to access emotion, so can you talk a little about your process?

I’m not a character actress. I can’t just put on a nose or be Richard III. I’m still using Liv and my experiences, allowing them to come out through me. Somehow. I can’t explain it. Other actors have methods. I had an interviewer years ago who seemed to like me as an actress, but he said I wasn’t an actress but just this human emotion walking around. Maybe I am, I don’t know, but that’s also what being an actor is. It’s the only place where I feel safe and good.

Those characters couldn’t be more different.

It’s the words, and what’s happening through them. I have that in me. I have a lot of anger, a lot of bad stuff in me. A lot of stuff that I never get to use. A lot of things are happening in my soul when I’m by myself. I read a lot and I meet a lot of people, see movies that have nothing to do with me. Two men loving each other, I know what that’s all about when I see it, even if it’s never been my experience. If you ask me to do that, I can do it because I recognise it. Once I recognise it within me, it somehow comes out. In Passion of Anna, where I’m lying all the time, I told Ingmar that I never lied. Of course I do, but that’s not what I told him. So he makes this movie about Anna, who lies a lot. There’s that long close-up, he longest he ever did at that point, I think – eight minutes or something – I had no idea that I’m blushing because she knows she’s lying. He just kept the camera going, kept the close-up when it was supposed to go somewhere else. I’m a sieve, and a lot of actors are like that. It’s hard to explain.

Which must make it especially hard when you don’t have Bergman’s words, but still need to find the character. Sorry to bring it up, but I just saw Lost Horizon…

Haha. That wasn’t acting! I was in Hollywood! The same for the other actors there too. It wasn’t acting, I don’t know what it was, but it was fun. I was the only one who just had fun, I think. I know Burt Bacharach had a nervous breakdown. For me it was just an adventure. I was 30 years old and in Hollywood. Same with that 40 Carats. How can I act that? I was 30 and could barely speak English, but was supposed to be a 40 year old, sophisticated New Yorker, falling in love with a 20 year old, but they gave me this wonderful actor the same age as me.

Everything was wrong. It was Liv trying to be an actor in a Hollywood movie, but I was so horribly miscast, there was no truth there. But then the same year, I got a wonderful script with Gene Hackman and maybe I was bad but I had a great time. That was acting, it was a character. It only counts when your soul is part of it, and whatever soul I had with Lost Horizon, I was in a Hollywood movie and got to dance with Gene Kelly, and it was nobody’s fault but my own.

It’s surprising you never worked with Woody Allen during that period. Weren’t you guys dating at one point?

He only dated me to get to Ingmar, to hear about Ingmar Bergman. We didn’t date, we just went for dinner. To him, everything Ingmar was Ingmar. I was Ingmar! Have you heard about their meeting?

I have, but I’d love to hear it from you.

This is 100 per cent the truth. We went for dinner, and he didn’t drink alcohol at the time, but I did. It was always, ‘Ingmar, Ingmar, Ingmar.’ I said, ‘Ingmar wants to come and see me in A Doll’s House,’ and he was all, ‘Oh my god, do you think I can meet him?’ So I phoned Ingmar on his island and said, ‘Woody Allen would like to meet you, do you want me to arrange it?’ He came to see the matinee of A Doll’s House and was leaving the next day. He was staying at the Pierre Hotel and came with his wife and agreed to the meeting. So my next dinner with Woody, I said, ‘Oh, Ingmar would really like to meet you.’ So after the play, Woody waited outside the theatre and took me in his limousine to the hotel. He was so nervous he was shaking. This was his idol, really his idol. Woody was probably Ingmar’s idol too, but Ingmar would never say that out loud. We take the elevator up, knock on the door, and Woody and Ingmar just look at each other.

We go in to the table where someone is serving us food, and I swear to god, they did not talk. Bergman’s wife and I didn’t have much in common, so we spoke about food, while the men just stared at each other. At the end of the meal, Woody says, ‘Thank you Mr Bergman,’ and we left. Outside, Woody says to me, ‘Thank you Liv, what an honour!’ When I got home, I called Ingmar, who said, ‘Thank you Liv, what an honour!’ As far as I know, they never spoke again. Geniuses are very careful around each other. When two meet, you have to be very careful.

The Ingmar Bergman centenary retrospective runs at BFI Southbank until the end of March.

Published 10 Feb 2018

There’s a fascinating backstory to the Swedish master’s little-seen 1950 thriller This Can’t Happen Here.

We journey to Fårö, a remote island in the Baltic Sea, in search of Sweden’s enigmatic master.

The Swedish master’s 1957 film is a deceptively accessible arthouse staple.