Ingmar Bergman is a colossus of world cinema. Literally: his blown-up image, complete with beret and visionary gaze, is currently emblazoned on the side of London’s BFI Southbank as part of a centenary retrospective of his career, from the ’40s to shortly before his death in 2007. Through masterworks such as Cries & Whispers, Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal and Persona, Bergman established himself as a master of artful gloominess.

Not included in the BFI season is the director’s little-seen spy thriller, This Can’t Happen Here, from 1950. Its omission is unsurprising considering Bergman actively sabotaged its release by withdrawing it from circulation. Long thought lost, a version has been known to intermittently wash-up on that shoreline of forgotten cinema, YouTube. He was miserable and ill at the time of filming. He only made it, he later recalled, because he had two ex-wives and five children to support. Yet the effort Bergman went to to destroy the film suggests something deeper than professional embarrassment.

Not for the last time in Bergman’s career, the behind the scenes story begins with a tax row. In response to higher entertainment taxes the Swedish film industry ground to a halt for a number of weeks in the winter of 1950-51. Keen to bank a hit before the start of industrial action, Svensk Filmindustri head Carl Anders Dymling proposed a film about a ring of Soviet-backed spies operating under the radar of the Swedish state.

Although thrillers were atypical for Swedish cinema of the ’40s and ’50s – this was long before Scandinoir became a thing- Hollywood was hooked on the idea of Europe as the playground of secret agents (America, after all, did not officially have an intelligence agency until 1946). Thanks to adaptations of Graham Greene, Europe provided possibilities for noir beyond the criminal underbellies of urban America.

There is something deliberately convoluted to the plot of This Can’t Happen Here. Atkä Natas (Ulf Palme) is a spy for the Baltic state of Liquidatzia planted within the émigré community in Sweden. His loyalties, however, are up for grabs as he intends to defect to America, buying his passage in exchange for a list of undercover agents. A visit to his estranged wife Vera (Signe Hasso) complicates matters as he confesses to her that he has sent her family to a labour camp. Vera poisons Natas while he is asleep and makes off with his spy list.

Natas is discovered by fellow Liquidatzian agents who happen to have developed an antidote to Vera’s toxin. They also uncover his plans to defect and spare his life on the condition that he retrieves the stolen list. Vera meanwhile alerts the émigré community of traitors in their midst. Events culminate in a series of set piece chases as Liquidatzian spies turn on Natas and then assail Vera.

If Dymling’s aim was to produce a Greene knock-off marketable to American and British audiences it is curious that the film deals with a subject that is unlikely to have resonated outside of Northern Europe. This Can’t Happen Here is situated in a particular political moment. Outside of NATO and nominally neutral, Sweden occupied a peculiar gateway point between the Soviet sphere and the West. There were a number forces in Swedish society that wanted the government to take a harder line on communism and be more partisan in its Western alignment and equated the communist threat with the country’s wartime trauma. According to historian Lars Fredrik Stöcker the Baltic refugee community became the poster child for one of the most important anti-communist lobby groups of its kind in Post-war Sweden.

Rushed into production a year before the government formally ended its NATO neutrality in 1951, could it be that This Can’t Happen Here was a part of something bigger than its makers were immediately aware? One of the film’s recurring motifs is the contrast between the peril inflicted on the film’s refugees and the benighted ignorance of much of the Swedish public. Bergman milks this irony for all its worth, deploying several juxtapositions of levity and jeopardy. In one of the more gripping scenes a meeting of Liquidatzian refugees takes place at the reverse side of cinema screen. As they weed out the mole a Donald Duck cartoon is being screened for a room of giggling children. If the point weren’t clear enough a sinister henchman spells it out: Sweden is a county of “beautiful, slumbering people” blissfully unaware of the horror that is to come.

We know from the director’s subsequent rejection of the film that This Can’t Happen Here was not the film that Bergman wanted to make. But if it wasn’t propaganda, what was it? Prior to production he had met with several Baltic refugees and was deeply affected by their plight. Speaking in 1968 he makes clear that what haunted him was his inability to do justice to the “humiliation” felt by the refugees. This, he says, “is something I’d really like to take up some day.” Bergman would explore the idea of humiliation on many occasions throughout his career, not least 1968’s Shame that sees a couple from a war-torn island forced from their home and disgraced.

Closer still to the concerns of his 1950 thriller is The Serpent’s Egg which was, incidentally, made during Bergman’s self-imposed exile from Sweden due to a politically-motivated investigation into his tax affairs. This 1977 films depicts an immigrant couple who discover the sinister workings of a shadow state in Weimar-era Berlin. Its vivid opening – a slow moving black and white crowd trudging silently onwards leads into a title sequence set to lively ragtime – harks back to the ironic juxtapositions that structured his 1950 film. Here as then, Bergman is pointing to a society oblivious to the creeping menace that is to engulf them.

What This Can’t Happen Here reminds us is that, for all his acclaim as a director of austere chamber pieces, Bergman was an eclectic filmmaker who challenged himself by working in a variety of genres, from horror (Hour of the Wolf) to slapstick (All These Women). It’s likely that the thriller genre appealed given his admiration for Alfred Hitchcock, in particular how he shot long sequences in confined places, “weeding out everything that is irrelevant”. We see this at work in This Can’t Happen Here when Vera poisons her husband. Resting the camera above Natas’s body Bergman lets the moment play out as Vera disposes of the evidence in the background. By holding the shot Bergman gives the scene the peculiar eeriness of unfinished business. He would use a similar technique for a disturbing scene in Face to Face when Liv Ullman’s character is attacked in her home. The camera, at a distance from the event, remains still and helpless as the horror unfolds.

This Can’t Happen Here may be Bergman’s only spy film, but his interest in espionage is evident across much of his filmography. The intercepted letter or diary is a recurring plot device, revealing a conspiracy against the protagonist. The camera itself takes on the role of the spy, closing in on aggrieved faces in a way that can give his films an uncomfortable intimacy. In Autumn Sonata, a character tells the viewer that he likes best to watch his wife when she doesn’t know he’s there. By breaking the fourth wall in this unusual way Bergman makes us complicit in this act; but is it admiration or is it more like voyeurism? Cinema is an act of interloping on the most intimate moments in the lives of others. Few filmmakers probed the moral discomfort of this phenomenon as completely as Bergman.

Published 13 Jan 2018

We journey to Fårö, a remote island in the Baltic Sea, in search of Sweden’s enigmatic master.

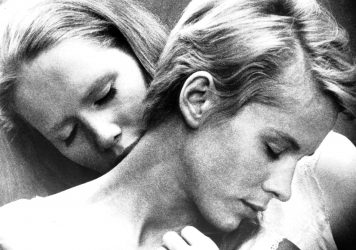

Ingmar Bergman’s enigmatic masterpiece still shines with a piercing intensity after 50 years.

The Swedish master’s 1957 film is a deceptively accessible arthouse staple.