The beguiling star of Sebastian Meise’s Great Freedom reflects on his career so far and the future of cinema.

If you missed him in one-take wonder Victoria, you doubtless noticed him in Michael Haneke’s Happy End, delivering a crazed karaoke and dance rendition of Sia’s “Chandelier:” German actor Franz Rogowski caught viewers’ attention from the moment he stepped in front of a camera. These two early roles made particularly effective use of his striking physicality, inherited from a background in dance and theatre. But Rogowski, who recently turned 36, also has a face made for the movies.

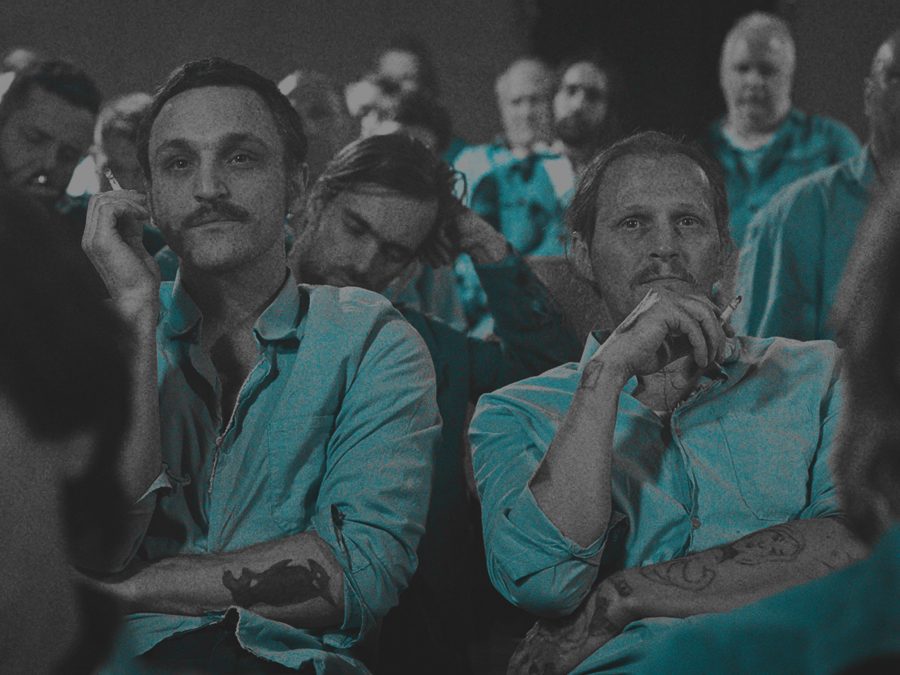

In Sebastian Meise’s Great Freedom, the ravages of time spent in prison across three decades mark themselves on his physique, but his character Hans, imprisoned for being gay in a Nazi concentration camp then in a German prison, evades the cruel logic of self-preservation that the homophobic Paragraph 175 sought to impose.

It is almost frustrating to see Hans repeatedly put himself in danger by courting potential partners and pursuing risky romances while in jail, and a genuine source of worry for some of the prisoners he gets involved with. But Rogowski’s unique, striking features, simultaneously open and closed-off, frank and timid, give life and cohesion to a character who does not seek danger, but simply freedom.

“If characters carry the weight of a whole story on their shoulders, by verbalising their actions and explaining what they’re doing, where they’re coming from and what’s going to happen, who is the good one and who’s the bad one, I prefer to listen to a podcast,” Rogowski tells LWLies. While his character in Great Freedom isn’t straightforward, the actor explains that he never actually thought this would be a difficult role to get to grips with. “It was really a gift, to not have to explain it all through words, but to smoke a cigarette, have a look, open a door, touch a body, embrace a friend – those are very archaic materials to talk about friendship, love, tenderness, longing, loneliness, violence.”

Though his career is still in its relative infancy, Rogowski’s filmography so far signals a performer who is very particular about the kind of cinema he wants to be a part of. “One of the few authorships that an actor can have is to curate the offers and to choose the right movies,” he explains. “I don’t really like characters that need to explain their existence or justify their actions, through drama that is invented by a director. I’m more interested in structures that give a voice to the image itself, or to the space, the sound, the body, and the fantasy, so that cinematography can actually take place.”

He describes his approach to his work as one not based so much on knowing lines and hitting precise story beats, but rather on his rapport with his fellow cast members and the moments they share, their silences, positions, vibrations. “It sounds a bit esoteric, but it’s actually the same thing as you and me here, having this phone call. This is also what you do when you play a scene.”

It’s a vision of cinema that has already aligned him with some of the most respected and formally exciting directors of our time, from Michael Haneke to Christian Petzold (in 2018’s Transit and 2020’s Undine), Angela Schanelec (in 2019’s I Was at Home, But) to Terrence Malick (2019’s A Hidden Life) as well as Ira Sachs in the American director’s next film. Though he has appeared in more commercial fare, Rogowski is more comfortable in a kind of cinema that does not follow expectations or easily fit into boxes.

“It’s not only about what the story is about, it’s also what the story is not about, and how explicit it is, but also how non-explicit a story can be and still have a right to exist,” he adds. Great Freedom certainly does bring to light the horror of a Germany where a law criminalising homosexuality was maintained in its extreme, Nazi-era form until 1969 (and only fully repealed in 1994), but it is more love story than didactic history lesson; like Hans himself, it reveals our conformist biases by circumventing them.

Now a star of arthouse cinema, Rogowski is keenly aware of the difficulty of bringing to life unconventional films, and of how lucky he is to have found success in such a difficult field. “I know a lot of colleagues who are much better actors than me, and they just have to do the offer that comes in because they need to pay the rent,” he adds.

Refreshingly candid about how his “emotions and insecurities” are useful to him as an actor but may be obstacles if he ever were to become a director (“I’m very curious and interested in those things, I just think that I’m not there yet. I might be there in five years”), Rogowski comes across as a very sensitive and thoughtful man, more conscious than most of his place in the cinema ecosystem and its challenges.

He says that the early days of the pandemic led him to a “great depression” as he worried about his future, but that this worldwide crisis also made him realise what kind of cinema he loves, “and it’s often a cinema that is not so obviously serving one purpose, not so obviously selling one product.” He does not believe Marvel or Netflix are bad per se, but that it is often pretty obvious that these projects are only created to “gain power, make money, or sell products.” At the same time, he also finds a lot to be desired about some arthouse films.

The pandemic, he tells me, made him reflect on this particular question of “how relevant cinema is and how relevant it should be.” In a time of crisis, for the world at large and for cinema in particular, he finds more and more of the film industry – be it in festival curation or in the scripts that he receives – move to one extreme or the other: either towards a purely commercial cinema, or towards “relevant cinema made by people who already know everything, for people who already know everything.”

Rather than necessarily serve either a commercial or political (or virtue-signalling) purpose, he thinks cinema should also be worth something just for being cinema. “It’s the art of creating energy, or value, or something by combining different moving images of one scene or two scenes,” he explains, “and in the combination of those, something miraculous can happen.” Rogowski is indeed fortunate to be able to pick his projects, but as long as he continues to walk the less beaten path in search of a truly artful cinema, we are the lucky ones.

Great Freedom is released in cinemas on 11 March. Read the LWLies Recommends review.

Support our independent journalism and receive monthly film recommendations, exclusive essays and more

Become a memberPublished 9 Mar 2022

Sebastian Meise’s profoundly sensual second feature is anchored by a standout performance from Franz Rogowski.

Paula Beer plays a woman with a supernatural secret in this unconventional modern-day fairy tale.

There’s shades of Casablanca in Christian Petzold’s riveting period romance, set in Nazi-occupied France.