Sebastian Schipper’s sensational single-take thriller is an ode to the art of filmmaking.

With the rise in prominence of digital video cameras, filmmakers can shoot any old shit and then build a movie in the editing suite. Hit ‘record’, let the actors prance about for a few hours in the hope of eliciting at least a minute of gold, repeat to fade.

Back in the good-old-bad-old-days when film was a valued commodity and planning was paramount, you had to know exactly what you wanted to do and say in advance. Filmmaking was a case of forming a cogent statement and then building it as best you can. Now, we can just blurt out anything and as long as there’s a lens being pointed in our general direction, and we’ve got ourselves some cinema.

Sebastian Schipper’s Victoria offers a modern ode to that classical form of filmmaking which elevated cold, hard preparation to the level of an art. The film was shot in a single continuous take between 4.30am and 7am on 27 April 2014 on the streets of Berlin’s southwestern hipster enclave of Kreuzberg. There are no invisible edits or fudges – everything you see happens in real time. As with Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman, there is the faint whiff of gimmickry to the enterprise, but at least with Schipper’s film he gives the tantalising impression that the entire movie is always on the verge of falling to pieces. Birdman had production sheen, where this has true grit. By the end, its actors are panting wrecks, entirely drained by this madcap undertaking.

Victoria (Laia Costa) is our guide through a distressingly eventful pre-twilight sortie in which carefree post-pub frolicking takes a surprise turn for the deadly. We meet her as she’s chugging back shots at an underground techno club and unsuccessfully attempting to chat up the barman. Then, in that special way that only happens when you’re half-cut on schnapps and staggering through the streets with no place to go, she starts gabbing with a small gang of young men and they become fast friends.

Though the men are presented as cheeky ne’er-do-wells, Schipper declines to profile them as archetypes straight away. For its opening hour, it gives us a blissfully honest and freewheeling portrayal of tipsy camaraderie, the likes of which are seldom captured with such heady nostalgia. Victoria is game to be part of their various monkeyshines, such as robbing booze from the dozing proprietor of an all-night grocer, or hollering abuse at a passing cop car. The motley crew even spirit her away to a rooftop hideaway on a grim tower block which offers a striking panorama of the sleeping city.

Frederick Lau’s mouthy, puffy-eyed charmer Sonne leads the gang, clad in a scraggy tracksuit top and with cigarette constantly dangling from his bottom lip. The small ensemble attain a state of perfect harmony in these early scenes, making their interactions feel entirely natural and the ensuing frisson of romance wholly plausible. As Victoria and Sonne start to coyly flirt, it’s incredible how Schipper presents two characters who are clearly besotted with one another, though each refuses to let down their guard lest they annihilate the sense of fun dictated by the occasion.

These scenes are so charged with euphoria and joy that it comes as something of a disappointment when they come to an end and the serious second act kicks in. All this was a slowburn set-up for another, more generic plotline, as Victoria’s devotion is tested when she’s pulled in to help the guys with an urgent criminal endeavour. This section of the film is more impressive on a cold technical level, dispensing with much of the messy humanity of the opening salvo. Where Sonne was once a chancer with a twinkle in his eye, he’s now a whiny sad-sack who – having known her for just over an hour – is comfortable allowing Victoria to risk her life to help them save theirs.

Logistically staggering though it is, Victoria is half a great film and half an okay but silly film. The single take strategy makes total sense, and it does manage to supercharge the simple material without drawing too much undue attention to itself. But with its story being split so cleanly in half, it’s hard to decipher what – if anything – the film is trying to say. Victoria herself works in a cafe having departed from her dream of becoming a piano virtuoso, and maybe the film has an underlying conservative streak where it says that none of this would’ve happened if she had been more discerning and less impulsive. At 138 minutes it also outstays its welcome by a good 30 minutes, but there are good stretches of this film which touch on the sublime.

Published 31 Mar 2016

Another one-take wonder, this time from Germany.

When it’s good, it’s really damn good.

Unwieldy by design, it does just try a little bit too hard to impress.

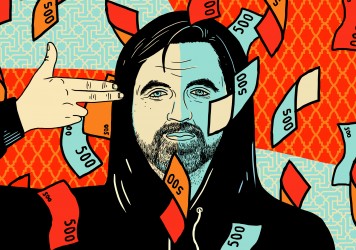

The German director of Victoria reveals the craziest thing he’s ever done for love.

Director Peter Strickland’s sumptuous, all-female S&M fable is his greatest film to date.