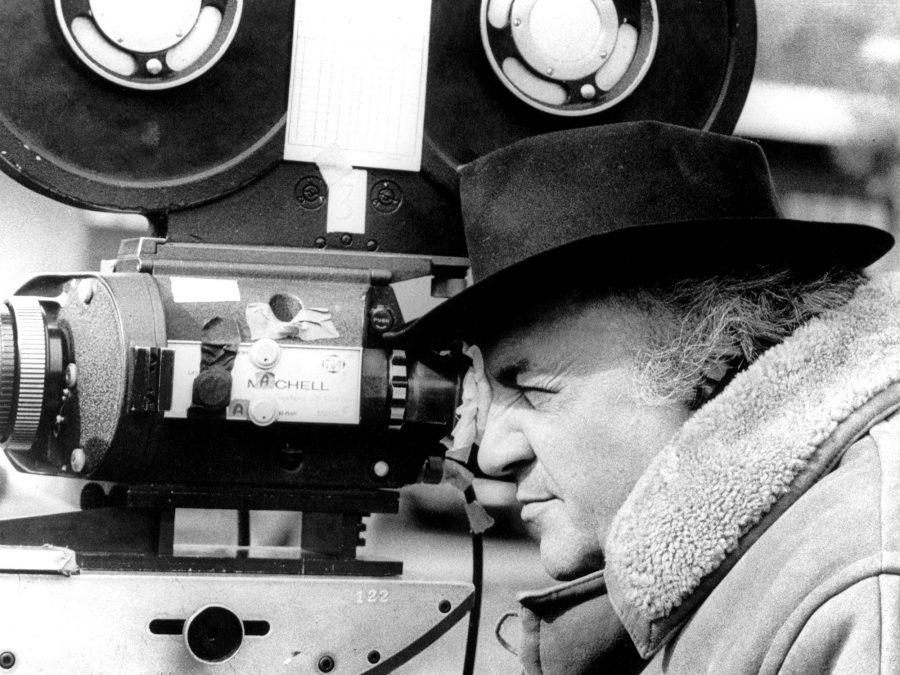

Fiammetta Profili reflects on her time working with Federico Fellini during his final decade.

While La Dolce Vita is back in UK cinemas to mark the centenary of his birth, there’s a chapter of Federico Fellini’s filmmaking career which is often overlooked. A two-month retrospective at BFI Southbank affords an opportunity to see the five films (starting with 1980’s City of Women) from his neglected late period, back where his singular visions belong.

One person who remained close to Fellini during this time was Fiammetta Profili, who worked as his personal assistant from the early ’80s through to his death in 1993. We gave her a call at her home in Rome to chat about the final decade of arguably the best-known name in world cinema.

LWLies: Tell us about your first encounter with Fellini.

Profili: The first time I met him, I was working in a theatre and he’d come to see an actor, the guy who’d dubbed Donald Sutherland in Casanova. Of course, I was absolutely in awe because he was a very charismatic character. The first thing we all noticed, straight away, was the fact that he had an incredible sense of humour.

How did you come to work with him?

Well, three years went by because he already had a personal assistant, who then left to go do something else, so he was looking for someone. It began because he needed to translate a treatment of [his 1983 film] And the Ship Sails On into English. He knew that I spoke English so he asked me to do that translation. Before taking me to Cinecittà where he would open his office for the preparation of the film, he took me to dinner with his wife Giulietta Masina, to ask her if it was a good idea to hire me as his new personal assistant.

What did a typical day look like for you?

Fellini didn’t shoot films one after another because they would take so long to make, so there was a lot of down time between productions. When we weren’t actually making a film, I’d work with him on the casting before production and then post-production would begin. He’d receive mountains of mail, which he was adamant about answering personally, so we’d have to work on that. Then he’d have ideas about possible projects which he’d dictate to me. Of course there were no computers at the time, so that would all be done on a typewriter. We’d have meetings with producers and the many stars and personalities who, when they came to Rome, would only want to meet the Pope and Fellini.

So were you based at Cinecittà?

Only during production and maybe a bit of post-production. Otherwise he kept an office in Rome.

His 1987 film Intervista was shot at Cinecittà and shows the studio in its all its faded glory. What was it like working there in the 1980s?

Well, Fellini just couldn’t ever imagine filming on location. Whatever he wanted to portray he had to build so he could have it just the way he wanted it. Rimini and Venice were built there from scratch, as was the entire ship in And the Ship Sails On, on a sea made of plastic. It was important for his vision to get these things exactly as he saw them in his mind. So Cinecittà was his kingdom where he could put all of this into practice. He only really lived when he was filming or preparing. When he came to the studio it meant that he was finally starting a film, and that was the best time of his life.

The ’80s were a difficult time for Fellini, with those later films not being as well received as his earlier, canonical pictures. Did he struggle to get those films made, especially given his demands to build everything from scratch, presumably at great expense?

Things were made even worse by the fact that, as he went on with his career, he got into the habit of not writing scripts at all. He’d write a few pages, just the idea, and that was it. So, of course this made it almost impossible for him to find producers who would give him money without knowing how much the final cost would be. It got harder and harder for him, and he finally had to rely on producers who had lots of money and just wanted the prestige of saying they’d produced a film by Fellini.

Was there much tension or competition for space at the studio between him and Dino de Laurentiis, who was also making huge productions there at the time?

Not at all. Dino de Laurentiis just kept sending Fellini scripts, for every single film he made in those years. They’d all be American blockbusters so Fellini would just laugh and that would be that. But Dino wanted Fellini for everything. He sent him one script, which Fellini gave to me to read, saying, ‘Tell me what you think.’ I told him it was really the most ridiculous story I’d ever read, about some girl who works in a steel factory and dances, it was really crazy. It turned out to be Flashdance, which he never would have directed, but turned out to be this huge success. Fellini always used to make fun of me and my commercial intuition afterwards.

You received a casting credit on both Ginger and Fred and Voice of the Moon. Fellini is famous for the faces in his films, so how did that process work?

All we had to do was spread the word that Fellini was casting at Cinecittà and people would just start flocking in. People knew that he often worked with non-professional actors, so they’d just come and say things like, ‘People tell me I have a Fellini face, so here I am.’ He’d try to get as many of those people into the films as he could. I’d try to screen people first, but he just wanted to see everyone. He enjoyed the interaction immensely and had this special gift where he would say, ‘I have chosen you as the person who owns the restaurant,’ and this person would suddenly say, ‘That’s incredible because my father used to own a restaurant and I grew up working in one.’ He always used to be able to guess something about these people that had something to do with their real lives.

There’s a sequence in Intervista where Fellini – playing himself – is casting the role of Brunhilde in the fake production of Kafka’s Amerika. He certainly had a type when it came to casting women…

He was just fascinated by women. He was endlessly curious about all the different types of women – the different personalities and thought processes. When a woman turned up he’d perhaps stay and speak with her for longer. He had this gift where when he was speaking to you he made you feel that you were one of the most important people in the world. They all came out feeling so flattered and excited by all the attention he’d given them.

You had the chance to work with Mastroianni on Ginger and Fred.

They were just so close. They’d not be in touch for maybe a couple of years and then they’d meet again and it’d be like they’d never been apart. Mastroianni had complete trust in Fellini, he’d do whatever he told him and didn’t care about reading a script before. For Ginger and Fred, where he played the alter-ego of Fellini, he had to deal with Fellini’s problem of losing his hair. Fellini asked him to pluck out his hair so that he’d appear more bald, and Mastroianni just did it – an actor, at his age, plucking his hair out with the risk of it not growing back – it’s amazing, I think. He was such a good man, so easy about everything.

The other face in Ginger and Fred is perhaps just as emblematic of the Italian cinema, that of Fellini’s wife Giulietta Masina. It had been more than 20 years since they’d worked together by that point.

There really wasn’t a role for her in the films in between, and he used to be very impatient with her on the set. He’d excuse himself by saying, ‘Giulietta was so much a part of me, like my arm or my hand, that I shouldn’t need to explain anything. She should know what to do without me having to tell her.’

Was she around during the other productions during those later years?

She’d come and visit for the day sometimes, but that’s about it.

What do you think it was about the later films you worked on with Fellini that meant they didn’t really connect with audiences and critics at the time?

Fellini was very upset about growing old. He thought he was ageing even when he wasn’t that old, and it certainly changed his character and his mood. He kept his incredible sense of humour up until the end, but he was definitely a bit more pessimistic in his later years, which must have affected his creativity in some ways.

One of the greatest moments in all of the later films is the wonderful reunion between Fellini, Mastroianni and Anita Ekberg in Intervista, where the two stars dance in silhouette behind a projection of them dancing three decades earlier in La Dolce Vita. Do you remember the day that was shot?

It was very emotional. We were there in Anita’s house, and everyone had the feeling that we were doing something really special. She was so happy to have this opportunity, and it was just incredible to be a part of that moment.

La Dolce Vita is in cinemas nationwide now. A two month retrospective of Federico Fellini’s films plays through January and February at BFI Southbank.

Published 18 Jan 2020

Dawn plays an important role in the Italian director’s 1960 film La Dolce Vita.

Read an exclusive extract of a long-lost conversation between these innovative French filmmakers.

By Matt Thrift

The screen icon speaks candidly about her remarkable career, and her complicated relationship with the late Swedish master.