This year’s EIFF showcased a diverse crop of homegrown films, from a monochrome Cornish curio to a love letter to Dundee.

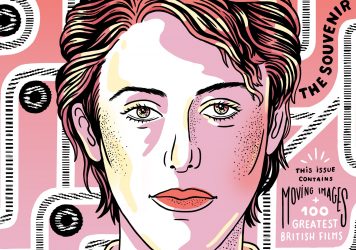

British cinema has a long-standing tradition of reflecting the country’s social, political and economic state, and 2019 is no different. Ray & Liz, the debut feature from photographer-turned-filmmaker Richard Billingham, artfully portrays the everyday struggles of a family on the breadline. On the other end of the class spectrum, Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir filters a young woman’s burgeoning first love through the prism of wealth and privilege in Knightsbridge.

This year’s Edinburgh International Film Festival featured a promising selection of homegrown films from established and emerging directors. There was a sense of a collective reckoning with the current state of affairs. How do we continue forward when it so often feels that as a nation we are moving backwards? The films selected as part of the festival’s ‘Best of British’ strand branched off into different directions, whether that be to borrow from the past for prescience, or to avoid the present completely through escapist narratives.

The cream of the crop was Mark Jenkin’s Bait, a strange time capsule piece which several critics have already dubbed the first true Brexit movie. The film follows Cornish fisherman Martin (Edward Rowe), who is scraping by selling sea bass to the local pub as his village’s industry succumbs to seasonal tourism. As if it has been plucked from the ocean, muck and grime scrubbed off for presentation, the film feels like a relic from a bygone era thanks to its anachronistic visual aesthetic.

Shot in black-and-white on a hand-cranked 16mm Bolex camera, Bait doesn’t hide its imperfections but rather celebrates them. Those imperfections – spots and scratches resulting from the film stock being process by hand – are part of the package. Harsh close-ups accentuate the physical performances of the mostly non-professional cast of actors. Violent cuts are used to draw a contrast between the wealthy tourists and the hardened locals. The film is so singularly immersive that the moment a character takes out an iPhone induces whiplash. It’s pure anger and frustration condensed into raw celluloid.

More explicitly political, the autobiographical Farming from first-time director Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje is almost excruciating to watch. The title refers to the practice that was common during the 1950s and ’60s in which parents of West African or Caribbean origin would pay British families to foster their children. Enitan (Damson Idris) is one such child, sent away by his Nigerian family to a foster home in Tilbury, Essex for his aggressive temperament in the classroom.

Berated by racism throughout his childhood, Eni is taught to hate the colour of his skin. In one of many devastating scenes, he coats himself in talcum powder. At 16, Eni is lured into a skinhead gang, clinging onto the false promise that if he joins his bullies, he can’t be beaten by them.

Farming is a painful exorcism of demons. Memories are recalled with harrowing clarity, as if recently closed wounds have been split open once more. Internalised racism is a very real and serious issue among black people, but the film’s message is clouded by a clunky screenplay that is more focused on putting Eni through severe emotional and physical turmoil than conveying insight into the systemic racism that allows such abuse to occur in the first place.

Elsewhere at the festival, a pair of brooding period dramas explored the dangerous grip of patriarchy on young women. William McGregor’s Gwen sees a teenage girl’s peaceful life in the Welsh mountains come crashing down as her family is threatened by a coal mine looking to expand. Another coming-of-age story, Emily Harris’ Carmilla is a study of repressed desire through the perspective of a young woman who becomes enchanted by the unexpected arrival of a mysterious girl.

Both films are similarly grim and dour, but they use elements of horror to varying effect. Dread permeates Gwen, with tension building in minute increments: its single jump scare is impactful for how sparingly it leans on the gimmick. Meanwhile, Carmilla pairs body horror with the gruesome cycle of nature. The film’s potent sound design accentuates the sounds of the surrounding forest to an almost deafening level: worms squirming in wet soil; ants scuttling across a decaying tree.

Sadly, Carmilla is a derivative period drama, although both films are bolstered by impressive performances from their young leads. In particular, Gwen’s Eleanor Worthington-Cox is terrific as an innocent adolescent who is forcibly thrust into maturity. She flits between desperation and despair effortlessly even as she goes toe-to-toe with Maxine Peake as her surly mother.

Not everything in the ‘Best of British’ strand was inherently political though. David McLean’s Schemers, which recalls the director’s own coming-of-age, sees Davie (Conor Berry) and his mates band together to become music promoters, booking groups for local venues. Of course, it starts as a ploy to impress a girl, a trainee nurse Dave meets in the hospital while high on morphine.

In this sense, Schemers plays like Dundee’s answer to Sing Street. But where the Irish musical dips into fantasy, Schemers is more attuned to the peaks and troughs of reality: the teens have a run-in with some organised criminals. At the film’s spirited climax, the boys scrounge together everything they can to meet their contractual obligations with the “up-and-coming” metal band they’ve booked: Iron Maiden. In the end, they’re just kids with no idea what they’ve gotten themselves into.

Remarkably, Schemers is the first full-length feature to be made in Dundee, and it is a wonderfully evocative love letter to the Scottish city. From nights out at the student union to the diversity of the city’s music venues, the film celebrates the small things that make the city what it is. In the film’s most touching scene, Davie tears up at the sight of Dundee’s “twa” (two) bridges. “Same as Edinburgh,” he says, his voice quivering with pride.

The films at this year’s EIF prove that British cinema isn’t short on diverse and fresh perspectives from filmmakers of all walks of life. Exciting new stories continue to invigorate and prolong this island’s rich film history. Even if Britain’s political future is becoming increasingly uncertain, its cinematic future is looking bright.

For more on this year’s Edinburgh International Film Festival visit edfilmfest.org.uk

Published 29 Jun 2019

Shelagh Delaney’s voice stood out from the angry young men who dominated British cinema in the mid 20th century.

This special, expanded edition of the magazine celebrates British cinema and contains moving illustrations.

By Tom Beasley

Coastal towns have long been a source of nostalgia on screen, but this setting has come to signify something else in recent years.