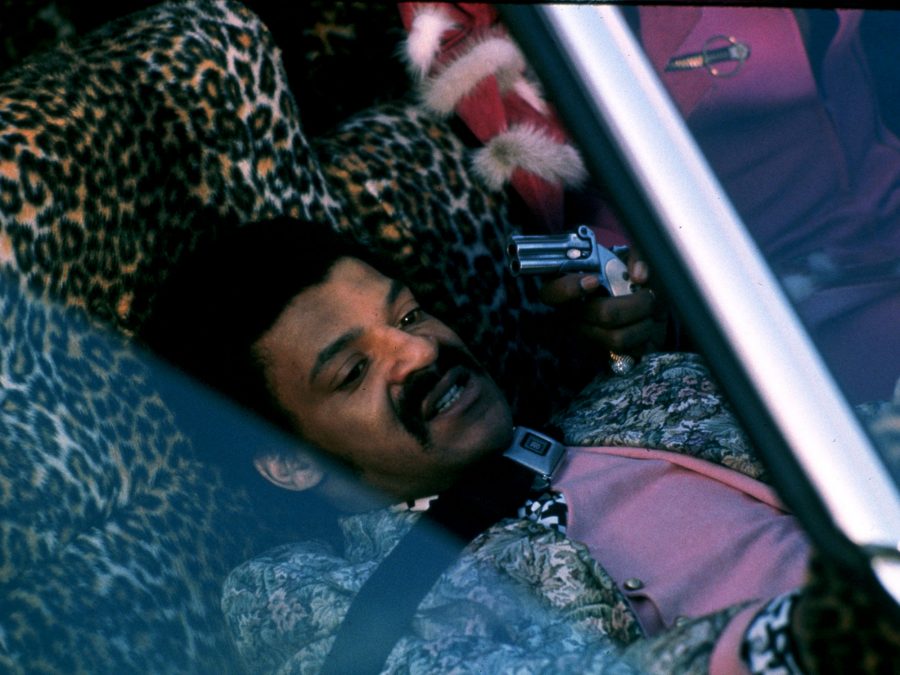

In the opening scenes of Gilbert Moses’ 1974 debut feature Willie Dynamite, the eponymous protagonist (Roscoe Orman) displays all the polished veneer of success within American patriarchy. He drives a flashily modified, purple-painted car (his name emblazoned across its customised plates) through the streets of New York City to the forecourt of a swanky hotel. If his ride is pimped to the max, that’s because Willie is an actual pimp – “seven women in the palm of his hand” go the lyrics to his Blaxploitation theme song, as he struts about in his expensive, colourful threads and furs.

More importantly, those lyrics also declare, “It’s no different from any other industry… He’s got to try to be Number One.” For all his particularities that are steeped in African-American subcultural stereotypes, Willie is also, more broadly, embodying the business end of the American dream. In case the point is missed, our first view of his operation – as his stable of prostitutes aggressively hook businessmen at a hotel convention – is unsubtly intercut with a monitor showing a speaker giving motivational advice to visiting entrepreneurs.

As the man on the TV screen discusses what has “made America’s little business grow into America’s big business”, we see Willie insisting to his youngest worker, Pashen (Joyce Walker), that his own ‘business’ is “a production line… just like GM, Ford and Chrysler, Willie’s coming through,” or telling a consortium of fellow pimps looking to organise and unionise, “I thought we was all capitalists – free enterprise, you dig. This kind of conversation could chase that off.” Willie’s rise and eventual fall trace a story of a particularly male strand of exploitative and insatiable money-making in America – often off the backs of women’s labour. Despite the flamboyance of his clothing and the swagger of his gait, Willie does not cut a particularly pretty picture.

Assured and arrogant, Willie regards both himself and his business model as untouchable. But then, as his fetishistic car keeps getting ticketed or towed, as his girls get arrested or worse, as a rival pimp (Roger Robinson) muscles in on his turf, and as ex-junkie, ex-hooking social worker Cora (Diana Sands), her assistant DA boyfriend (Thalmus Rasulala), a pair of cops (Albert Hall, George Murdock) and the IRS all circle to bring him down, Willie’s empire proves to be built on sand, and a careful deconstruction of his own – and capitalist America’s – identity begins.

Willie Dynamite’s very name encodes explosive phallic prowess, even if the literal gun that we see him packing in his pants is decidedly on the small side. When he’s eventually hauled before a court charged with, among other things, carrying a concealed weapon, and brought face to face with both a judge and his own horrified, heartbroken mother, the cracks finally show in Willie’s macho facade. It’s not be long before he is reduced to a broken, weeping wreck, tormented with guilt for the consequences of his treatment of women. All along we know that ‘Dynamite’ is merely a street moniker, but it is in the courtroom that Willie is truly cut down to size, as we hear for the first time his real and symbolic surname: Short. Meanwhile, his once celebratory theme song now addresses Willie as “King Midas… everything you touch turns to dust.”

So while Willie Dynamite might at first appear a paean to the pimp lifestyle, by the end it has become a moral fable of remorse and reform, with Cora its true hero, and with Willie having to reject the bling and braggadocio behind which he has been hiding in order to become a better member of his community. This is not only a film about conflicts and contradictions in black identity, but also a sly critique of capital’s ruthless upward trajectory.

Willie Dynamite is released by Arrow in dual format DVD/Blu-ray edition on 6 February.

Published 6 Feb 2017

By Anton Bitel

Don Sharp’s Psychomania is now available on DVD and Blu-ray.

These beautiful, revealing posters highlight African-American culture’s contribution to cinema.

By Matthew Eng

James Baldwin reclaims the spotlight in Raoul Peck’s magnificent film essay.