Between 10-12 March, 1972, Mayor Richard Hatcher hosted the National Black Political Convention in, not a convention centre in “progressive” cities like New York or Los Angeles, but a high school gymnasium in the “smokestack city” of Gary, Indiana. At the time, he and Carl Stokes were the only Black Mayors of cities with population exceeding 100,000.

Thousands of Black activists, artists, entertainers, elected officials and delegates from across the country journeyed into Hatcher’s hometown to partake in the making of an independent national Black political agenda. Rev Jesse Jackson set the scene in his first speech: “Brother Hatcher came up north and got a house in Gary and said to all of the scattered children in the various Black tribes across the nation, ‘Come home. I know my home is too small, brothers and sisters, but it’s home. Come home.’”

IndieCollect’s new 4K restoration of William Greaves’ Nationtime, wrought from the original print that was thought lost, begins with former news reporter Wali Siddiq sending home a roomful of journalists because the gymnasium was at capacity. But Imamu Amiri Baraka, the poet activist moderating, invited Greaves to document the convention himself; hence this 80-minute glimpse through Greaves’ naturally idiosyncratic point of view: unbroken handheld takes, extreme angles, whip pans and zooms.

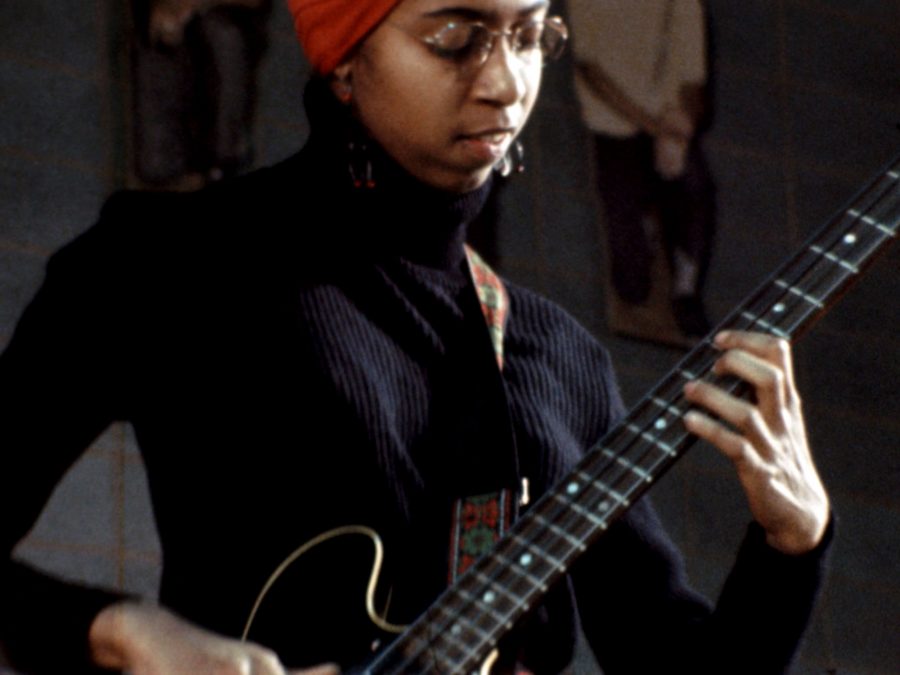

Not obscuring his intentions here, as he did in his meta Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One or lacing his intentions with irony, as when he directed propaganda docs like Wealth of a Nation for the UN and USIA, Nationtime sees Greaves operating in rare unironic form. Harry Belafonte recites poetry by Baraka and Langston Hughes over the film, which is interposed with Sidney Poitier’s voice of god narration, and an original score by Phil Cohran that riffs between the convention’s concerts.

The committee that originally drafted the independent Black National agenda was disillusioned with the concessions conceded by the US Government after the civil rights movement. Speakers demanded reparations, a reduction in the military and police budgets, untrammeled voting rights and the formation of an independent Black political party. Elected officials in attendance were not as radical, and despite the committee’s aims to upend the two-party system, Black democrats, republicans, socialists and nationalists alike were welcomed. The point was unity, not uniformity, a consensus between all of Black America at any cost and despite any differences.

The Black National Convention of 2020 organised by the Movement for Black Lives and the Electoral Justice Project drew inspiration from the ’72 convention, even as it was forced to take virtual form due to COVID. Greaves’ Nationtime is the most tangible point of reference to the past convention, and footage from the restoration is weaved throughout.

Of course, the 2020 convention also tackled similar issues like defunding the police, climate change, voting rights, intracommunal violence and indigenous land protection. It also featured Black musicians and expanded on its predecessor’s variety with a cooking tutorial by the Bronx Collective Ghetto Gastro, a look at a Black Puerto Rican owned jewellery shop, Afro Lunatika, and much more.

Today, it is clear that Black liberation should and ought to have been structured around the voices of Black trans women and men, and the 2020 convention is built around their leadership. The idea of an independent Black party, central to the ’72 convention, is now outmoded. “We’ve evolved into a rainbow coalition… An independent party would be limiting.” Jackson reflected 48 years later.

Experiencing the National Black Political Convention of ’72 through Nationtime, with Black cinematography, narration and music over all Black speakers and icons, and watching the Black National Convention of 2020 inspired by and expanding on the former, is a great relief from the white spectre that haunts so much of Black culture. In restoring Nationtime, a record of Black resilience has been preserved and the National Black Political Convention’s influence further affirmed.

Nationtime is released digitally via KinoLorber on 23 October.

Published 19 Oct 2020

By Leila Latif

A new documentary gives a voice to the silenced natives in Joseph Conrad’s colonialist novel.

Stanley Nelson offers a broad survey of the militant political party.

The multi-hyphenate has created a hypnotic, incisive score for Charles Officer’s socially-conscious crime-noir.