The multi-hyphenate has created a hypnotic, incisive score for Charles Officer’s socially-conscious crime-noir.

Saul Williams is a master of many mediums – poetry, hip-hop, acting, activism – and throughout his career he’s exhibited a keen instinct for knowing which will best serve his message of love and liberation. As a musician, he’s recorded with Nine Inch Nails and Allen Ginsberg; as a speaker, he’s visited 30-plus countries; as an actor, he’s reached Broadway (in 2013’s Tupac musical Holler If Ya Hear Me) and starred in a Sundance prize-winner (1998’s Slam).

In Akilla’s Escape, which premiered at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival, Williams plays the lead role of a marijuana dealer who is robbed on the eve of his retirement and endeavours to help one of the young thieves (Thamela Mpumlwana) escape the same cycles of gang violence he never could.

The crime-noir is heightened by Williams’ hypnotic score (co-composed with Massive Attack’s Robert “3D” Del Naja), capturing those cycles as nightmare loops, weaving between its protagonist’s traumatic youth and his tortured present, with Mpumlwana also playing young Akilla. For Williams and director Charles Officer, a thriller exploring masculinity and mythologies of gang violence allowed both to advance previous conversations they’d had.

“As Black men in the Americas, we’re thinking about these things off-camera more than we’re given the opportunity to think about them on-camera,” explains Williams. “How do we put an end to generational trauma? How do we successfully question patriarchal ideas and ideals that have been programmed into us? How do we thwart systemic suppression and oppression when we birth children who are once again born into it?”

Early on, Officer asked Williams whether he would contribute music to Akilla’s Escape, but it was only after filming that Williams was able to disassociate from the scenes he’d acted in, putting himself in the right space to provide the soundtrack.

An opening montage of archival footage and newspaper clippings, set to Bob Marley and the Wailers’ ‘Punky Reggae Party’, depicts Jamaican history as a gale of political unrest, inseparable from colonial intrusions and the rise of drug trafficking. Headlines charting the CIA’s 1976 efforts to destabilise the Manley government flash as a hand reaches for an Uzi submachine gun. Intercut with these images, Williams dances in a warehouse to the same bouncing needle drop.

“It was easier to choose that song than it was to clear it,” Williams reveals. No other soundtrack choice made the production jump through as many hoops – in fairness, no other soundtrack choice was Marley. The soundtrack broadly explores Jamaican musical history while charting its diasporic extensions: included are ’60s balladeer Jackie Edwards; ’70s roots reggae group The Gladiators; and modern EDM duo Zeds Dead (specifically, their bass-heavy ‘Rudeboy’, from the Jamaican slang term).

“From the moment the script came, I used it as this wonderful excuse to dive into Jamaican archives of sound,” says Williams. Marley, the global flag-bearer for Rastafari sound and ethos, was kept in heavy rotation, as were two other ’70s island icons: dub pioneer Lee “Scratch” Perry, and Burning Spear, whose roots chants exhibited a bracing political anger. Williams adds that he was equally inspired by Miles Davis’ spaced-out soundscapes, as well as minimalist composer Terry Riley, noted for innovative uses of repetition and delay.

He’s also a noted trip-hop fan. When Williams was approached by Officer, he was already deep into trading unrelated sonic experiments with Del Naja. Getting the go-ahead, he tested out their compositions in the mix – haunting synthscapes driven by skeletal beats and an air of distorted menace that seemed to fit perfectly. “It made sense in deepening the narrative and bringing out qualities Charles wanted in the genre of a crime-noir,” says Williams. “There was a depth necessary in the sound to complement that. It came about not easily but clearly, how those two worlds might connect.”

Ironically, the placement Williams agonised over most is the only instance in Akilla’s Escape where we hear his musical voice. An early scene of young Akilla being interrogated in a New York police station segues into neon-lit present-day Toronto, where the older Akilla is introduced. Bridging the timelines is ‘Skin of a Drum’ from Williams’ 2007 record ‘The Inevitable Rise and Liberation of Niggy Tardust!’. Over clanging crate drums and anxious violins from Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor, Williams contemplates his relationship to his father (“His completions won’t complete me / I’ve divided me by one”).

“That’s probably the one thing I fought Charles on,” says Williams, who was more focused on creating new beats than repurposing old ones. “It’s probably what led him to thinking I should work on the sound of this film, but it was too on-the-nose for me to see.” Between the song’s inclusion and Williams’ performance, Akilla’s Escape doubles as a meta-meditation on his career interest in breaking patriarchal cycles through art. He welcomes this reading.

“To play with these questions in a creative sense is liberating. You feel the possibility that, by facing this challenge publicly, it may touch something in someone else who’s also been in that uncharted territory of self-questioning. Maybe that will lead to something closer to an answer.”

Published 17 Sep 2020

The third feature from Chloé Zhao is an achingly tender look at one woman's life on the road.

By Thomas Hobbs

The singer-songwriter and rising film composer reveals how she was seduced by Krzysztof Kieślowski’s doppelgänger drama.

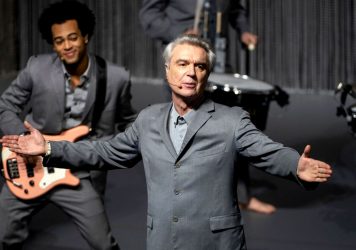

Spike Lee’s film of David Byrne’s acclaimed Broadway performance is a transcendent cinematic experience.