In a new series, we’re celebrating the films we loved that aren’t likely to dominate the awards race. Over the new few weeks, our writers make passionate arguments for the performances and craft that stood out to them, from blockbusters to arthouse and everything in between.

Todd Field’s screenplay for TÁR opens with a warning: “Based on this script’s page count, it would be reasonable to assume that the total running time for TÁR will be well under two hours. However, this will not be a reasonable film…” He continues to explain that the film will be guided by sound, filled with music. In practical terms, it’s generally understood that each page in a screenplay reflects (more or less) a minute on screen. Field’s screenplay is 94 pages, and TÁR is 158 minutes long.

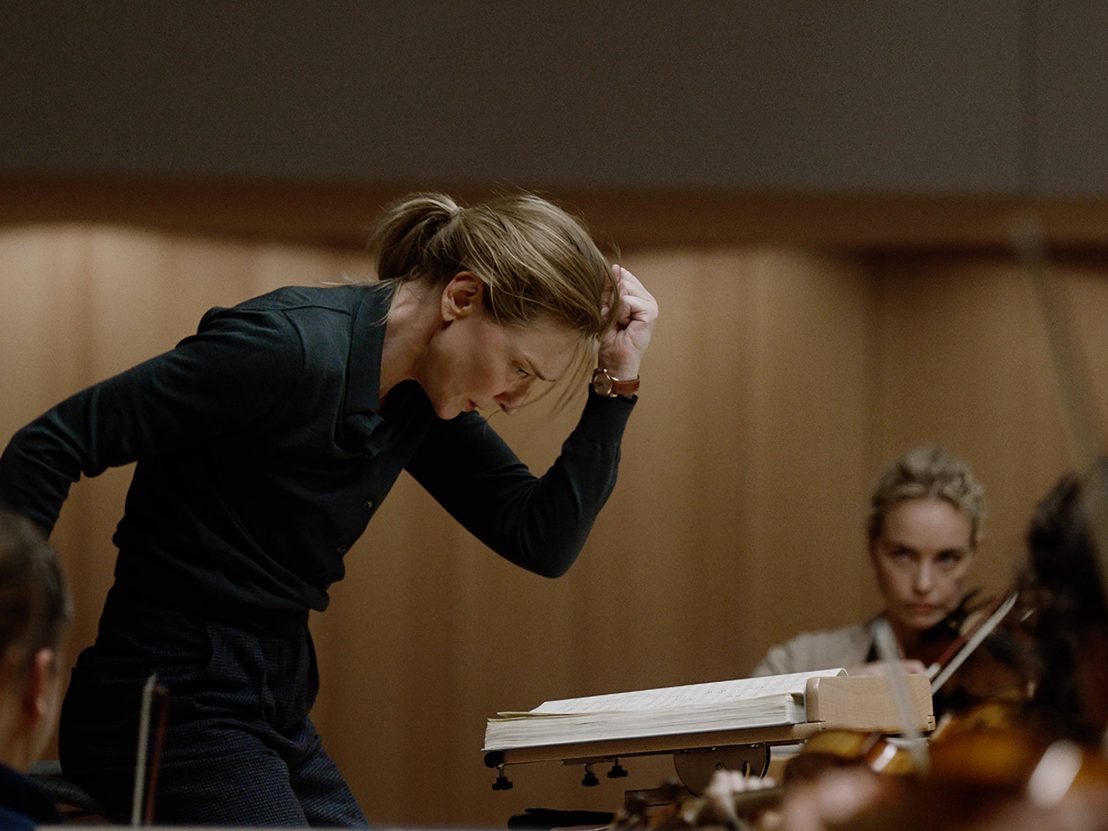

Watching TÁR, it’s clear that Field makes good on his warning. The film overflows with double meanings, varying tones, and enormous egos. Lydia Tár, a world-famous Maestra, may be precise, persuasive and proud, but she is not reasonable either. As played by Cate Blanchett, she’s highly charismatic but not reasonable – on the page, she’s borderline inscrutable. Yet, for all the majesty of direction, sound and performance that enliven the experience on the big screen, Field’s original screenplay stands as a majestic, ambiguous work. For all that goes unsaid (and unheard) in the reading, the truth of Lydia’s nature spills out in Field’s words.

A brief throwaway scene reveals a kernel of Lydia’s motivation. After rehearsal, she goes to the recording booth to speak with the Chief Lighting/Video Technician and Chief Sound Mixer. They complain about not shooting the rehearsal to disc, then ask her if she wants the files in WAV. She brushes them off, asking for .mp3s instead. “Just what people will actually be streaming,” she insists. She also wants the video “Stage A Left camera.”

On-screen, it unfolds as written. It’s short, it’s sweet, and it’s mostly delivered without emotional inflection. It suggests a lot about Lydia’s priorities, though; music falls behind her image, her need to be seen. For someone who presents as strict with herself and others, a guardian of great music and an arbitrator of taste, she either has little understanding of compression rates for musical recording or merely doesn’t care.

Though seemingly insignificant, this scene, when pushed against the much-discussed Juilliard sequence, for example, becomes illuminating. As she scolds a student for being “so easily offended,” as she defends Bach, one can’t help but wonder what she stands for as a conductor. Is she a genius, or is she just playing one for the crowd? As the offended student storms out, Lydia raises her voice, “If you want to dance the mask, you must service the composer. Sublimate yourself, your ego, and yes, your identity! You must in fact stand in front of the public and God and obliterate yourself.”

It’s unreasonable to assume that people always do as they say, but it’s clear that Lydia has done anything but sublimate herself, her ego and her identity. Even in this scene, unaware that she’s being filled by an errant cellphone, she’s performing for a crowd, performing the ins and outs of her ego-driven desire to be perceived as exceptional. There’s no indication that Lydia wants to impart real, practical wisdom to the room of students. She wants them to be made small in the enormity of her presence. When Lydia talks about God, she might as well be talking about herself.

If you’ve ever read a book about writing screenplays, most recommend avoiding the words “we see.” Yet, if you read many great screenplays, many writers address an imagined viewer. On the page, words first appear on Page 36 while Lydia leads a rehearsal. The words act as bolded text in a script like Field’s, already so sparse and allusive.

Tár leading a rehearsal. The sonic power of one of the world’s greatest orchestras with players from across the globe. Tár addresses them mostly in English. This is where we see the why and how of who she is. The art of the particular. The discipline. The only real reason that people put up with her.

This particular example leads the audience to see Lydia in a specific way that aligns with her self-image. The ambiguity of the full cinematic experience, rife with uncertainty and paradox, similarly unfolds on the page. While one would expect the words “we see” to reveal something tangible on-screen, an image, a colour, a fact (later in the screenplay, he uses the words to describe the first time we see Lydia’s bruised face), here, it is more of a suggestion than a fact. What, precisely, do we see?

Is it possible that Lydia Tár happens to be an image-obsessed egoist who also happens to be great at what she does? If she doesn’t care for the details of lossless files, can she still care about the performance? Does her egoism negate her hard work and talent? What about her abuse, her violence? As Field’s screenplay suggests that at this moment, “we see the why and how of who she is,” Lydia remains elusive.

Not all great screenplays become great films, yet so much of what makes TÁR such a compelling work of art began on the page. Though the movie unfolds almost twice the length of what was written, that’s built into the particular voice and tone of what was laid out on the page. It suggests strange rhythms and uncomfortable moments as scenes drop off suddenly and pick up elsewhere. As compelling as TÁR is, more viewings and readings complicate rather than streamline an interpretation. Much like its titular character, it’s entirely unreasonable and unknowable; that’s why it’s so good.

Published 13 Feb 2023

By Ege Apaydın

Cate Blanchett is on top form as a conductor who experiences a swift fall from grace in Todd Fields' piercing psychodrama.

BlacKkKlansman is the latest ‘Spike Lee Joint’ to feature a powerful, thought-provoking epilogue.

Starring as a concentration camp survivor attempting to rebuild her life in spite of considerable challenges, Hoss delivers a captivating and entirely convincing performance.