Spike Lee films often end so many times they invite a Rashomon effect. Ask five people how Do the Right Thing ends, and five different answers may come back. Does it end when Mookie hurls the trashcan through the pizzeria window? Or is it when Smiley pins the photo of Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X onto the flame-eaten wall? No, wait. Doesn’t Mister Señor Love Daddy forecast another day of unbearable heat over the radio? Are you imagining things, or do Mookie and Sal actually discuss insurance money the morning after the film’s climactic riot?

It wouldn’t be a Spike Lee Joint if the story was resolved straightforwardly, or if it didn’t feature a thought-provoking epilogue of some form or another. Sometimes Lee’s films stretch on for five, 10 or even 15 additional minutes, leaping through space and time, with or without the main protagonists. In addition to his signature dolly shots and direct-to-camera interludes, this artistic verbosity right before the end credits explains why Lee’s films are often accused of being indulgent. Indeed, entire books have been written about reading the filmmaker’s work through a lens of “excess”.

Yet these postscripts are more than an artistic tic or a product of lax self-censorship. When they work, they educe and evince the central themes of Lee’s work in a powerful and confrontational manner.

Lee continues this pattern in his new film, BlacKkKlansman. After all but wrapping up the stranger-than-fiction tale of Colorado Springs police detective Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) infiltrating the Ku Klux Klan in 1979, Lee goes out of his way to forge historical connections we might have missed. Up to this point, the film plays as a comedic yet harrowing snapshot of American racial tension: about breaking colour lines, about what it means to pass, about the political dilemmas faced by an African-American policeman, about the poison seed of racism that has infected the United States since the beginning and festers still. But as always with Lee, wait, there’s more.

BlacKkKlansman concludes with a furious montage. Donald Trump is shown remarking on the “very fine people on both sides” of 2017’s white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, which left a counter-protester dead and 19 others injured. Then, former Klan Grand Wizard David Duke (played in the film by Topher Grace) is shown at that same rally signalling Trump’s presidency as a watershed opportunity “to take our country back.” Most disturbingly, Lee ends this newsreel barrage with footage of the actual vehicular homicide that killed Heather Heyer a year ago this month.

It’s a bone-chilling emotional assault, but certainly not without artistic merit. The 61-year-old filmmaker, now in his fourth decade of challenging viewers, is doing so with form as well as content. In unambiguously connecting the past to present, Lee calls out the potential fictions of his own film and shatters whatever escapism came with them. BlacKkKlansman portrays ’70s white supremacists by turns as buffoonish basement beer swillers and as a new generation of bigots who would much sooner inject their bile into the political system than burn a cross. The epilogue reminds us they’re all brutalisers when empowered.

What’s more, the film’s final stanzas make it impossible to exit the theatre savouring the comedy, romance or action. Stallworth impersonating a white supremacist over the phone is entertaining, but the political forces circling this story are revealing as to how we arrived where we are today – an era when a reality TV star can attempt despotism and dog-whistle the prejudiced and intolerant into committing violent acts that amount to domestic terrorism. Suddenly, 1979 looks a lot like 2018, and people of colour are fighting the same fight, even as the oppressors shapeshift.

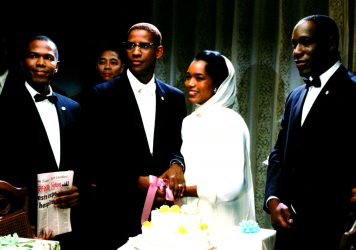

In Lee’s filmography, the long coda also makes for clear punctuation. Malcolm X concludes with a stirring eulogy for the slain civil rights leader and insists Malcolm’s spirit lives on in black children around the world. And in a rare optimistic example, Mo’ Better Blues, an otherwise Herculean tragedy of virtuoso trumpeter Bleek Gilliam (Denzel Washington), ends with a suggestion that there is untold nobility in a hero being robbed of his one great gift. Perhaps he can find joy in moderation and hope in balance. Meanwhile, Lee’s 2001 adaptation of David Benioff’s novel ‘The 25th Hour’ is a gorgeous and mysterious amalgam of fantasy and reality, simultaneously idealising and interrogating whether Edward Norton’s jailbound protagonist, who has squandered all his privilege, really deserves a second chance.

As in BlacKkKlansman, another subset of Lee’s epilogues challenges the conventions of the story preceding them. The director’s most overt and successful Hollywood film, Inside Man, tees up a flawless heist twist only to soldier past the big reveal and complicate the cat and mouse game between Clive Owen and Denzel Washington’s cop and robber characters. What if they’re all just cats and mice for hire, the film asks, and a finely-tuned thriller evolves into a character study with late-blooming heft.

Do the Right Thing has its own 25th hour. Formally confined to the hottest day of the year on a few Brooklyn blocks, the film lets its famous crescendo of pressure release in a denouement that feels at once hopeful and despairing. The cycles of black poverty, police brutality, and of history’s long and torturous arc, haven’t been remotely solved in their mere depiction. They’ll stretch on like the summer heat wave into the next day, year, generation.

It should be noted that there is a cost to this approach. Even an avid Lee appreciator knows how taxing on both patience and psyche his films can can be. As for BlacKkKlansman, it is not unreasonable to question whether we actually need to see footage of a real human being killed at the end of what is ostensibly a period buddy comedy. One could make a compelling case either way, or suggest that some kind of trigger warning is in order. There’s always the critical argument, too, that Lee occasionally stifles fascinating stories and performances in layers of meaning.

If not clarity, then, these epilogues create considerable depth. What may seem on first viewing like narrative imperfection is likely rendered more enriching over time. Film after film, Lee leaves audiences with a sense of unfinished business – enough so, perhaps, to jolt viewers into action, be it on behalf of a cause, or against their own comforts or biases, or maybe right back to the film for more.

Published 21 Aug 2018

Find out by joining the author of ‘Facing Blackness’ for a special screening of the director’s 2000 film.

A black cop infiltrates the Ku Klux Klan in Spike Lee’s fiery, fiercely funny takedown of institutional racism.

By Nadia Latif

Spike Lee’s epic biopic of the black civil rights leader offers only glimpses of the great woman behind the man.