Sam Raimi’s franchise midpoint is a perfect superhero sequel – a film with a sincere belief in humanity.

Ten years ago the disastrous third and final entry in Sam Raimi’s mega-budget Spider-Man trilogy crystallised the franchise’s reputation as silly, non-serious cinema. In hindsight, this brand of superhero entertainment stands in direct opposition to the current homogenous crop of po-faced comic book adaptations. But even that film, in which the hero faces his ‘dark side’ in the figure of Venom, hinted at the strained seriousness that has come to dominate the superhero movie landscape in the post-Nolan era.

The current status quo in the genre makes the absurdist, irreverent tone of 2004’s Spider-Man 2 seem all the more astonishing today. Most humour in the film draws on Peter Parker’s permanent status as a nerd – an awkward, nebbish presence outside of the famous costume. A naive man-child, Parker reacts to the series of brutal challenges he faces with a melancholic pout and a half-smile. His response to being repeatedly jostled in the street is an amused, embarrassed chuckle. The total lack of realism in Tobey Maguire’s career-defining performance places Raimi’s trilogy firmly in the realm of fantasy. There is no Actor’s Studio work being done here. Contrasted with more recent comic book fare, the thrill of a big action sequence is now perpetually dampened by an insistent awareness of disastrous consequences as embodied by the brooding of an Oscar winner, a shake of their head and an existential monologue.

Parker is presented here as hilariously and irritatingly passive, so much so that, in early scenes, the mature and assertive Mary-Jane (Kirsten Dunst) seems almost harsh for coming on strong and demanding respect from her soon-to-be beau. Yet nothing is arbitrary in Spider-Man 2, and as Parker’s passivity catches up with him, it reveals itself to be more than a mere comedic character trait, linked as it is into the overall arc of a film which sees Parker overwhelmed by his alter ego.

Raimi’s original Spider-Man from 2002 saw our hero learn that “with great power comes great responsibility.” The series of humiliations and disappointments that opens the second film – from a botched pizza delivery to a dispute with a tyrannical landlord – serves as a reminder that with human power comes human responsibility. If Parker wants to have a ‘normal’ life, he must follow the rules of interpersonal relationships and not disappoint everyone.

After meeting inspiring scientist Doctor Octavius (Alfred Molina, unforgettable in a nuanced performance), Peter gains the confidence to believe his academic intelligence is as much of a precious gift as his super powers. With great intelligence comes the even greater responsibility to use it, and Parker hangs up his Spider suit to focus on his studies, a change which gives him more time to concentrate on his home life and turn things around. It seems to be the perfect solution to his problems, were it not for his responsibility as a superhero.

Parker is soon recalled to his duties when Octavius becomes obsessed with a potentially world-ending invention after he morphs into the awesomely tentacled Doctor Octopus (an early triumph for photo-realistic CG and practical effects). Obeying only a selfish desire to bring his machine to completion and explore the full potential of his intelligence, Doc Ock puts people in harm’s way, including Mary-Jane.

It’s a powerful wake up call for Peter who realises that he has put his intelligence before his heroic powers for entirely selfish reasions. For a time he has been able to experience the praise and fulfilment that come with the skills he holds as himself, something he crucially has never been able to enjoy while saving lives as a masked hero. But such glory is simply not possible for Parker. He must face the sad truth that, in his case, pursuing a normal life would be a selfish act.

As such, the film offered up the promise of a franchise that would not select its villains at random, but rather thematically link them to the main character’s growth as both a hero and as a person. Yet, it was a promise swiftly dashed by the multiple villains and thematic incoherence of the 2007 threequel. Spider-Man 2 is a perfect superhero film sequel: able to stand on its own as a self-contained story while also extensively and intelligently drawing from and developing the characters and themes established in the previous episode.

Nowadays, Superhero sequels are, for the most part, aimed at hardcore fans who have the pre-awareness and commitment to follow confused storylines across past, present and future. Fan theories crudely engulf the screen as characters form alliances and separate out as they would in a soap opera. And this is not down to narrative necessity, but to create new thrills that are often as ephemeral as they are nonsensical.

In that sense, Spider-Man 2 belongs to a bygone era of franchise blockbusters. But this also comes down to ideology. Perpetually jolly, the film refuses to adopt the de rigueur misanthropy and pessimistic view on humanity articulated by the Ayn Rand-infused opera stylings of Batman V Superman. While Parker and Octopus are portrayed as similar but on different sides of the law, the latter is by no means the ‘dark side’ of the former. There is no sense of true, straightforward evil in the world of Spider-Man 2. Rather, we are presented with misguided, heartbroken and desperate people who have lost all sense of scale and responsibility.

The moment when Doc Ock finally comes to his senses is all the more moving precisely because of how badly he has acted previously. That Parker/Spider-Man would give him a chance to act like the kind human being he once knew makes for a heartbreakingly beautiful moment. It exposes the film’s sincere belief in humanity, the spirit of community and forgiveness. It is not because people are weak that Spider-Man must fight crime (see: The Dark Knight), but because he is the single individual given the (super) power to stop those who have strayed too far to be saved by a simple act of kindness. He is here when the empathy of people such as the doomed Uncle Ben of the first film, and the second’s moral arbiter, the lovely Aunt May, fail to bring desperate people to their senses.

Spider-Man is not all powerful. He is not a ‘God amongst Men’. He is a last resort against unregulated human violence. The film pushes the idea that men should not act as gods: Doc Ock creates an actual sun – a universe – before his Icarus-like fall from grace. It is because Parker is only human – and not a figure to be admired solely on the basis that he has supernatural powers – that the film is not afraid of ridiculing him. Contemporary superhero films rarely deviate from the idea of the hero as a perfect individual (as opposed to the weakness and fallibility of mortals). Their actions are questionable, but always justified as serving some greater purpose, and when they are purely selfish and violent, their existence is validated by the fact that they are simply cool and badass (see: Deadpool).

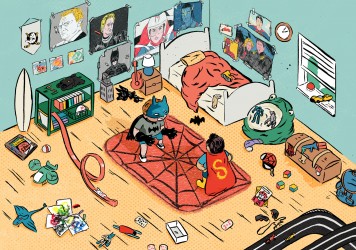

The contrast between Deadpool’s self-reflexive remarks about the ridiculousness of superhero tights and spandex, and the charming sequence in Spider-Man 2 where the hero and a random civilian talk about the discomfort of his tight costume, is a perfect illustration of a considerable register shift in superhero films. Spider-Man 2 could live with its character being essentially ridiculous, an invention for children. Deadpool cannot. Of course, like so many post-Iron Man Marvel films before it, Deadpool caters to a predominantly adult audience. Perhaps the kids are now grown-ups afraid to be taken for geeks? Constant self-reflexivity certainly speaks of an anxiety about enjoying silly, childish entertainment. Yet it’s in all the superheroic selfishness and disregard for consequences that we see something more insidious, a gross expression of some uncompromised masculinity now lost.

In a cruel twist of fate, the recent Captain America: Civil War serves as a reminder that, no matter how ridiculous or naive he might be, Peter Parker/Spider-Man is still one of the best superheroes. His powers are based on acrobatics, thus his action sequences in which he features are more thrilling and ingenious than any weaponised battle. That our hero would be disarmingly optimistic and oblivious to peril makes sense. His ingenuity and carelessness – his essential humanity – are what allows him to do the impossible and get himself out of the trickiest situations.

What do you think is the greatest blockbuster of the 21st century? Have your say @LWLies

Published 13 Jul 2016

By Ivan Radford

The first Avenger is a patriotic symbol of Us vs Them politics in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Twelve writers pin their colours to the tentpole in our survey of the best summer movies of the modern era.

Steven Spielberg’s beloved 1993 movie is about so much more than dinosaurs.