Cannes and controversy are cinematic soul mates. Since its inaugural edition in 1946, the festival has championed both emerging and established film talent while simultaneously generating headline-grabbing scandals – from the pigeon-related publicity stunt of 2001 to 2015’s “Heelgate”.

Yet its the Palme d’Or, Cannes’ highest honour, which consistently raises the controversy stakes. Heckling is par for the course (just ask Vincent Cassel’s brother, who bellowed his disdain when Gaspar Noé’s Irréversible screened in 2002) while counter-applause has become a popular tactic for dispelling positivity ever since The Tree of Life scooped the coveted prize in 2011.

In the long history of notorious Palme d’Or moments, however, one film stands out. Currently celebrating its 40th anniversary, Taxi Driver stunned festival spectators in 1976 with its visceral visuals and astute social observations. The audience jeered at the film’s premiere and became even more irate when the film’s director, Martin Scorsese, snubbed the closing ceremony by failing to collect his prize.

Taxi Driver is in many ways the ultimate product of New Hollywood. The script, by Paul Schrader, was drafted during a period of great social and political unrest. The Watergate Scandal and the conclusion of the Vietnam War had left the American people bitter and disenfranchised. With Taxi Driver, Schrader, who had recently overcome a derailing nervous breakdown, captured the mood of the nation. He painted a violent picture of modern urban life, something which evidently caused great offence among some audiences.

When you consider the film within the wider context of the era, it’s easy to see why it ruffled so many feathers. Scorsese was widely accused of glamourising violence at a time when the horrors of a hopeless war were still fresh in people’s minds. His protagonist, Travis Bickle, was viewed as deeply cynical, racist and radical in his anti-establishment attitudes. With Bickle, Scorsese ripped away America’s security blanket, strongly implying instability and replanting the seeds of doubt and fear. The 1976 Cannes Jury President, playwright Tennessee Williams, criticised the film for its visual “abuse”, which he likened to a Roman gladiatorial spectacle.

At the same time Second-wave feminism led audiences to question the misogynistic nature of Taxi Driver. The film’s two female characters, Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) and Iris (Jodie Foster), are depicted as incomplete, acting as purely physical objects of desire for men. Foster was 12 years old at the time, and her age raised questions about both female exploitation and the sexualisation of minors, highlighting just how far feminism had to go.

Yet of all the controversies surrounding the film, the graphic ending was by far the greatest cause of panic. Despite Scorsese and cinematographer Michael Chapman digitally muting the bloodshed in order to secure a lower rating for its theatrical release, the extreme violence and lack of closure was a major concerned for viewers used to sanitised Hollywood productions where the story is neatly wrapped up – the villain always punished for their sins. In this sense, Taxi Driver’s impact and influence cannot be overstated. It remains a defining moment in American cinema, its legacy sealed on Europe’s biggest stage.

Published 10 May 2016

Wes Anderson’s brilliant debut, which turns 20 this month, channels the youthful spirit of Mean Streets.

By Matt Thrift

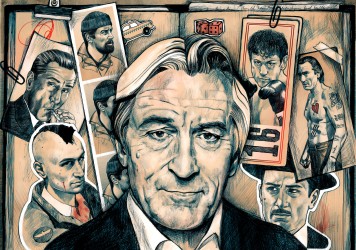

Dirty Grandpa may be an indefensible dud, but the actor’s recent output is nowhere near as bad as everyone seems to think.

By Paul Risker

With Martin Scorsese’s seminal crime drama finally out on Blu-ray, we gauge the film’s enduring influence.