Martin Scorsese is a filmmaker who requires no introduction, his staggering contribution to American cinema having been the subject of countless studies and retrospectives over the years. He is, to put it in plain English, one of the all-time greats. To celebrate the extraordinary career of this master director, we’ve undertaken the mammoth task of revisiting and ranking his entire filmography, from the early, lesser-seen works right through to his most revered cinematic milestones and everything in between. Check out the full list below, then share your personal Scorsese Top 10 with us @LWLies.

Scorsese teams up with Robert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt for an extended commercial for a Macau casino. The flimsy plot centres on Bobby and Leo’s competition for the lead in Marty’s next picture; the actors playing vain, bickering versions of themselves. With Terence Winter’s script made up entirely of terminally unfunny banter, only Scorsese walks away with his dignity intact – in front of the camera, that is (the direction amounts to a pile-up of CG-augmented cliche). The price of said dignity? $13m apiece for a week’s work. Fair enough. Matt Thrift

This 20-minute puff piece on fashion designer Giorgio Armani is notable for marking the first collaboration between Scorsese and Jay Cocks, who would go on to write the screenplays for The Age of Innocence, Gangs of New York and Silence. Available on a compendium DVD comprising Scorsese’s short films, it’s worth seeking out, but only if you have a penchant for uncharismatic, immaculately-tailored Milanese elites. Adam Woodward

A 24-minute episode made for Steven Spielberg’s hugely hyped series, Amazing Stories: Mirror, Mirror all but collapses under the weight of its competing impulses. Working from a cute concept by Spielberg, After Hours scribe Joseph Minion brings little to the table in psychological terms (the brevity of the format an apparent millstone), while a bland Sam Waterston – as the writer haunted by a looming killer every time he looks in the mirror – offers few clues as to the point of a bitesize morality play in the Tales From the Crypt mode. MT

Scorsese returned to the mean streets of New York for the pilot of Vinyl, a ’70s-set HBO series centred on music mogul Richie Finestra (Bobby Cannavale). Sadly, the script’s lack of direction means not even the impeccable soundtrack or trademark bursts of extreme violence manage to make the feature-length episode more than mildly entertaining – largely due to the sense that Robert De Niro and Harvey Keitel’s Mean Streets characters could well be up to no good just off camera. The show was recently cancelled after just one season. Jacob Stolworthy

Though barely distributed, Scorsese’s urgent, searing debut feature Who’s That Knocking at My Door did wonders for the reputation of its then 25-year-old director – not to mention its breakout star, Harvey Keitel. By contrast his follow-up, Boxcar Bertha, arriving five years later, did little to suggest that Scorsese was the real deal. A rough-hewn Bonnie and Clyde knock off, the scuzzy fingerprints of pop producer extraordinaire Roger Corman are all over this down and dirty picture. Less so Scorsese’s, who was very much a gun-for-hire here. One for Marty completists only. AW

With Michael Jackson’s schnoz making global headlines in the mid-’80s, it’s fitting that the title video from the superstar’s 1987 album would prove to be so on-the-nose. Written by Richard “Clockers” Price, the full 18-minute cut of Scorsese’s film may be the singer’s most forthright attempt at confronting questions of racial identity before he took a sledgehammer to subtlety in the early ’90s with ‘Black or White’, but there’s little escaping the camp credentials of a leather-clad riff on West Side Story. The biggest pop culture icon on the planet gets out-charisma’d by an unknown Wesley Snipes in a role that was originally intended for Prince, whose comments on the matter sum things up rather nicely. MT

It speaks volumes that Scorsese’s first ever foray into filmmaking focused on perhaps his most innocent protagonist. This nine-minute comedy short was made while Scorsese studied at New York University’s Tisch School of Arts in 1963 and follows a writer who grows obsessed with a picture on his wall. Frantic from the get go, the film is an unashamed merging of Buñuel and Bergman while the mind-bending climax intriguingly suggests Scorsese’s career path almost veered in a totally different direction. Still, the film’s overarching mantra – “Life is fraught with peril” – could apply to nearly all of the director’s films to have followed. JS

While it certainly has more going for it than Scorsese’s more recent stab at TV piloting, the debut episode of Boardwalk Empire is beset by the same problems – namely, the need to get enough plates in the air so they can keep spinning for a further 50-odd episodes. Watching it, you get the sense that Scorsese is lending little more than the most superficial aspects of his brand to proceedings. Despite costing a reported $18m, the level of historical accuracy is below that of the director’s superior period pieces. Still, a lead role for Steve Buscemi can never be an entirely bad thing. MT

A six-minute short produced for the 9/11 fundraiser, A Concert for New York City, the film sees Scorsese take to the streets of Little Italy for a whistlestop tour of the area in which he grew up. The film serves as a brief celebration of the area’s shifting ethnic demographics over the years, as Scorsese offers both fond reminiscence and contemporary portrait of a neighbourhood in which a large Chinese community coexists with the remnants of its Italian predecessors. A trifle, perhaps, but an affectionate, microcosmic glimpse nonetheless of a social landscape forged by its immigrant population. MT

While showcasing many seeds Scorsese would go onto plant in his own films – there’s musical numbers (New York, New York), gangsters (Goodfellas) and loquacious narration (here’s looking at you, Jordan Belfort), this second short of Marty’s importantly highlights what so influenced the man to pick up a camera in the first place (this short’s ending in particular directly riffs off Fellini’s 8 ½). For that reason alone, it’s an essential work. JS

Shutter Island is all about trickery. An adaptation of Dennis Lehane’s novel, it tracks US Marshal Teddy Daniels (Leonardo DiCaprio) as he investigates the disappearance of a patient from a hospital for the criminally insane. Through evocative imagery and blatant homage (Shock Corridor is clearly his subject), Scorsese layers this mind-bending thriller with intentionally ambiguous overtones so as to throw us off the scent. But is Shutter Island an underrated entry into the director’s canon or is it emblematic of Scorsese resting on his laurels? Whichever way you lean, one thing that can be said is that no two views are the same. JS

Tight and impersonal, Andrew Lau’s Infernal Affairs got its business done in 100-minutes. For his remake, Scorsese adds the best part of an hour, largely failing to cohesively fuse narrative concerns with the Oedipally-ridden weight of his loftier thematic ideals. Mark Wahlberg took the lion’s share of plaudits – and an Oscar nomination – but the best performance here belongs to Matt Damon in the film’s least showy part; witness the caught-red-handed scene with Vera Farmiga (saddled with a thankless role). Sadly it seems that even Scorsese couldn’t tame Jack Nicholson, who – even when he’s not waving a dildo around – readily serves up slice after slice of grade-A ham. MT

Having placed the spotlight on Bob Dylan for documentary No Direction Home six years previous, Scorsese turned his sights to The Beatles – more specifically George Harrison – with this unparalleled glimpse into the life of who was often the unsung genius in the corner. Developed alongside Harrison’s widow Olivia, the tender contributions – ranging from surviving Beatles Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr to fellow musicians Eric Clapton, Jeff Lynne and Tom Petty – make this an essential, if a little languorous, delve into the life of arguably the greatest Beatle. JS

A man shaves in the bathroom mirror. Once finished, he lathers up and shaves again. Blood pours from his face. He slits his throat to the strains of a cadenza – ‘I Can’t Get Started’ – impotence and masochism. Unnecessary action resulting in unnecessary bloodshed, taken to self-flagellating extremity. 1968: brute force and blunt allegory. A credit reads, ‘Whiteness by Herman Melville’ – Vietnam another elusive white whale; a direct, final title card driving the point home. Or all just films school lols symptomatic of an overindulgent arthouse diet? MT

Whether or not you enjoy Public Speaking will likely depend on your capacity to withstand the rat-a-tat comic patter of Fran Lebowitz, the feisty subject of Scorsese’s 2010 docu-profile. The sardonic New Yorker is certainly on uncompromising form here, yet the film’s casual tone at least eases us into the conversation. As Lebowitz sets the world to rights, you can’t help but think of another strong-willed, anti-establishment Scorsese protagonist. Incidentally, she also happens to drive a chequered cab. AW

Or: Martin Scorsese’s A Series of Unfortunate Events. After Paramount cancelled The Last Temptation of Christ in 1983, the director realigned his attentions back to independent filmmaking for After Hours, a screwball tale following a night in the life of Griffin Dunne’s word processing protagonist. As he meanders innocently from one bizarre encounter to another, it becomes tough not to hand this vibrant Scorsese outing acknowledgement for the creation of most future Coen Brothers films; it’s hard to imagine the Dude abiding without it. JS

It may be his most straightforward star vehicle (Newman, not Cruise), but Scorsese’s sequel to 1961’s The Hustler remains as solid a studio throwback as any delivered by a treading-water auteur. Attempts to personalise the material begin with an opening voiceover from Scorsese, the film never better than in its early stages. If the recognisably energised style rarely transcends the decorative (that opening aside), there’s an enjoyably predictable – and predictably enjoyable – momentum to the age-old narrative and character dynamics. While the method students that populate so much of his work tend to walk away with the lion’s share of credit, one need only look at the performance Scorsese gets from Tom Cruise for evidence of one of the premier actor’s directors in the business at work. MT

Only Scorsese could make an advertisement for Catalan wine maker Freixenet into a beguiling love letter to the master of suspense. This faux documentary short suggests the director has discovered three and a half pages of a ‘lost’ Alfred Hitchcock film and is making it into a film. Cue Bernard Hermann’s frantic North by Northwest score playing out as lead actors (resembling Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint) reenact a suitably Hitchcockian – and wholly fabricated – plot. A reference-ladled love letter from one cineaste to another. JS

Those in thrall to Shine a Light would be well-served by plunging into this seven-part documentary series. The opener was helmed by Scorsese himself, with later episodes directed by the likes of Charles Burnett, Wim Wenders and Clint Eastwood. A rough-and-ready introduction to the sounds of the Mississippi Delta, Scorsese shoots on low-grade DV, allowing guitarist Corey Harris to take the lead in interviewing sidemen to the greats and unsung heroes in their own right. Less refined than his archive or concert docs but no less essential for those with even the vaguest interest in the evolution of a sound. MT

No Direction isn’t a biography of Bob Dylan. Well, it is that, but it’s also a film about America, telling as it does the story of the times via the prodigious folk prince’s distinct brand of musical poetry. Cinematically, No Direction Home – which takes its name from a lyric in Dylan’s 1965 song ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ – is indebted to a film widely regarded as the first ever rockumentary, DA Pennebaker’s Dont Look Back from 1967; some of Pennebaker’s original colour stock footage of Dylan on tour even made it into the final cut, culled from hours of unseen tape donated by longtime Dylan associate Jeff Rosen. If you ever want to show someone what it meant to be American during the early to mid-’60s, show them this. AW

Charting 50 years of The New York Review of Books, Scorsese’s most recent documentary is propelled by the rhythm of language andkundu ideas. As a chronologically hop-scotching journey through the paper’s history, Scorsese (and co-director David Tedeschi) wisely allow its contributors’ words speak for themselves, eschewing soundbites for a rich layering of theme through montage. One suspects it’s an editorial job of which its central subject, the NYRB’s estimable editor Robert Silvers would be proud. “The ideas were sensuous,” says Colm Toibin of the paper’s attraction, a notion not lost in the filmmakers’ account of a 50-year crusade to engender dialogue on the path to change. MT

More than mere warm-up for Mean Streets, Scorsese’s debut feature transcends the patchwork aesthetic qualities borne out of a protracted production. Ground zero for auteurist readings of the the filmmaker’s work, the film wears its cinephile heart on its sleeve, charmingly foregrounding its debts to Fellini, Cassavetes, Truffaut, Godard and – most literally – Ford and Hawks. Mastering the swiftly trademarked, contrapuntal use of pop music from the get-go, Who’s That Knocking at My Door maps the fault lines between sex and religion that Scorsese has examined throughout his career. The Girl (Zina Bethune) may not be afforded a name, but this remains as forthright a critique of masculinity and ego as any of the director’s films to come. MT

Preceding Silence in Scorsese’s unofficial ‘Faith’ trilogy is Kundun, his autobiographical account of the 14th Dalai Lama’s exile from Tibet (The Last Temptation of Christ came first). A beguiling departure for the director, Kundun – written by the late Melissa Mathison – is not without its pitfalls and controversies (the film’s depiction of China almost derailed Disney’s relationship with the country). Yet there remains plenty to admire, not least the marriage of Scorsese, cinematographer Roger Deakins and composer Philip Glass, whose expertise kicks into gear for a memorable final act that quickens the pulse thankfully warranting the often tedious meditative journey. JS

Around the time of The Aviator’s release, Scorsese stated that he had no desire to continue making big $100m movies. Which in hindsight seems a little disingenuous given that the five features he’s directed since 2004 were all made on roughly the same budget. The point here is that Scorsese has always been artistically-driven and self-aware enough not to let himself be sucked too far into the Hollywood machine. With very few exceptions, he’s always prized smaller, more personal projects over high-pressure studio fare; his boldness and willingness to take risks not unlike Leonardo DiCaprio’s eponymous protagonist, Howard Hughes. The Aviator isn’t Scorsese’s best film by any stretch, but watching it you get a clear sense of these two great American visionaries, both equally bold and ungrounded in their respective ambitions. AW

Sandwiched between Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore was Scorsese’s first Hollywood production. It is, however, almost defiantly independent in spirit and style – both in its immediate telling of a young woman’s search for identity and liberation, and through the director’s acknowledgement of the expectations and limitations placed on him by the studio. Ellen Burstyn is terrific as the title character, an aspiring singer whose unwillingness to bend to society’s wills sees her struggle to find her place in the world. Often read as a straightforward tale of feminist angst, Alice is actually completely untethered from ideological strictures. Simply put, it’s a film about going your own way. AW

Scorsese swapped the swing of New York, New York for San Francisco rockabilly with The Last Waltz, a concert film showcasing The Band’s 1976 farewell show in the venue they first performed at 16 years previous. Split between leg-slapping renditions of renowned tracks and interviews with the charmingly poised band members, Scorsese bears the good judgement to recline and let the musicians do the talking. The Last Waltz hits all the right notes, heralded by Scorsese’s opening instruction: ‘This film should be played loud!’ and backed up by the inclusion of pioneers Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell and Muddy Waters. A necessity for anyone who’s ever heard a bar of music. JS

Scorsese’s opening contribution to the portmanteau film, New York Stories ranks as one of his finest achievements, a stylistically aggressive and experimental work inspired by Dostoyevsky’s ‘The Gambler’ that comes in under 50 minutes. Where the decorative nature of his direction in the likes of After Hours and The Color of Money comes off as superficial, here he offers a stylistic tour de force wholly simpatico with the brutishly nervous, violent energies of his protagonist. Opening on abstracted details to the strains of Procol Harem – a recurring soundtrack motif – Scorsese examines the tensions between love, life and art from the subjective perspective of Nick Nolte’s egocentric painter; as quintessential a Scorsese protagonist as they come. MT

“My films would be unthinkable, really, without them.” That’s how Martin Scorsese once described the influence of the Rolling Stones on his work. Filmed at New York’s Beacon Theatre during the band’s 2006 ‘A Bigger Bang Tour’, Shine a Light is a concert film that achieves the rare feat of capturing the special, inexpressible connection the surviving band members have not just with their adoring fans, but with each other. Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Ronnie Wood and Charlie Watts are hardly in their prime here, but Scorsese masterfully reveals how the Stones’ enduring rock ‘n’ roll spirit has kept them in such good shape. Musically speaking, anyway. AW

“These days it seems like American cinema is all there is,” says Scorsese in the opening moments of his second, vast documentary on the movies. “All the other cinemas are secondary, including Italian cinema, and that really worries me. In fact, it’s the reason I’m making this documentary.” Much like his previous film on American movies, Scorsese begins on an autobiographical note, the sense of nostalgic reminiscence foregrounded with memories of family viewings of Roberto Rossellini’s Paisan, before affording the movies in question a greater depth of analysis, of personal resonance. While we naturally cherish every narrative feature Scorsese turns his hand to, there’d be no complaints here if the rest of his post-Silence career were spent producing such personal epics of cinematic academia. MT

If nothing else, Scorsese’s most recent doc makes a fierce argument for his fiction and non-fiction work to be considered inseparably. He’d already tackled the career of Bob Dylan in his wide-ranging 2005 film No Direction Home, but for this return to the elusive musician’s discography, the focus is on a specific period in the icon’s life on the road. Charting Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue, a series of low-key gigs in small venues that Dylan shuttled between across 1975-76, the film soars in its stage performances, largely taken from the singer’s self-directed Renaldo and Clara. On the surface, Rolling Thunder Revue appears to be a straightforward mix of concert footage, backstage shenanigans and talking heads interview, but Dylan proves a slippery custodian of his own history, mythology and essential unknowability – which Scorsese, like any good disciple, appears more than happy to indulge. MT

From the first shot, in which the filmmaker shares a bath with his subject – larger-than-life Taxi Driver gun-salesman, Steven Prince – Scorsese makes no bones about the directed nature of his documentary portrait. As Prince tells his tall tales, ranging from hilarious to horrific, Scorsese keeps up a dialogue with both subject and crew. From asides to an unseen editor and DoP Michael Chapman, to the referral to pre-production notes on anecdotes he wants to capture on film, said deconstruction reaches its peak as Scorsese reveals as much about the rehearsed nature of storytelling as he does his magnetic raconteur, and by extension the very notion of documentary truth. MT

A pulpy remake that’s better than the original, Cape Fear was the biggest commercial hit of Scorsese’s career until The Aviator blew it out of the water a little over a decade later. Much of the film’s success lies in De Niro’s all-consuming central turn as Bible-loving, cigar-chewing rapist Max Cady, whose lurid tattoos, Hawaiian shirts and lispy southern lilt instantly set him apart as the most cartoonish villain of De Niro’s career. The stormy finale aboard a hijacked riverboat was at the time the most ambitious action sequence Scorsese had ever attempted. It’s certainly apt that Cady/De Niro appears to be channelling the shark in Steven Spielberg’s Jaws: he’s cold-blooded and unrelenting to the last. AW

Early in the film, Scorsese talks about repeatedly borrowing a pictorial guide to cinema from the New York Public Library as a child. For him, many of the films existed only on the pages of said book. This wonderful documentary served a similar purpose for cinephiles of a certain age, many a list compiled off the back of the filmmaker’s affectionate recollections and judiciously illustrated analyses. Tracking down a copy of Delmer Daves’ The Red House, say, was nigh-on impossible back in 1995; it seemed to exist only in the tantalising glimpses found on a worn-out VHS of this, Scorsese’s personal canon. An intoxicating treasure map of the American cinema from one of its leading champions. MT

Few filmmakers possess the clout – or the inclination – to mount such a personal project on so grand a scale. A family movie as hymn to film preservation and an aching tale of loss both personal and cultural, Hugo sees Scorsese adopt the latest filmmaking tools to pay homage to the earliest. Fittingly this tribute to that pioneering cinematic magician, Georges Méliès, resulted in the most effective use of 3D post-Avatar; not least evidenced in a stunning update of the Lumiere brothers’ The Arrival of a Train, here seen careering across a dream-stage of CG-augmented cinematic artifice. The filmmaker’s manifesto – beyond illuminating the need to safeguard a medium’s heritage – is that of his protagonists; to conjure the impossible, Scorsese forging an up-to-the-minute digital realm as a means to bring the dreams shared with Méliès to life. MT

As Las Vegas fixer Sam “Ace” Rothstein, Robert De Niro is coolness personified, keeping things together even as his world crumbles around him to prove once and for all that living in a mobster’s paradise is no picnic. Yet it’s a career-best Sharon Stone who steals the show as Ace’s pill-popping, treacherous wife, Ginger – showing that Scorsese is just as adept at eliciting strong performances from women as he is men. Her sudden death, teed up by De Niro’s snappy, snarling narration, is one of the most consummately staged scenes in the director’s entire filmography. AW

While Who’s That Knocking at My Door made literal its quotation of Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo through a series of magazine-sourced stills, Mean Streets fuses its hanging-out-with-the-guys vibe to Vitelloni-banter, riffing more extensively on the earlier film’s superlative party scene. If its presentation of the city harks back to the unvarnished immediacy of Shadows or Little Fugitive – and forward to the nocturnal, claret-hued hellscape of Taxi Driver – the masochistic psychological and interpersonal conflicts en route to a Brooklyn Bridge Golgotha see the violence of cultural and religious imperatives cast in operatic terms. MT

There’s a scene late in The Wolf of Wall Street where stockbroking scamp Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) devolves into an anti-hero in front of our eyes: after being asked for a divorce, he smacks his wife Naomi (Margot Robbie) around the face. It’s a shocking, stray act of violence in a film largely devoid of them and hammers home the fact that, until that point, you’ve been watching an irreverent, dynamic old-fashioned feature up there with his most enjoyable. Only Scorsese could have adeptly weaved this sprawling film and its madcap characters into a coherent whole that improves on each view. And not just for beer-guzzling uni students. JS

One of the chief pleasures in revisiting a filmmaker’s entire back catalogue lies in the hope of a film’s ascendancy when viewed with fresh eyes. Gangs of New York is a prime example of this, not least given the coincidence of its current political potency. As one of the last great studio backlot productions, it’s a film whose tactility is foregrounded to the point of artificiality. Scorsese has never made a western, but that genre’s self-defining approach to historical revisionism and myth making finds an urban equivalency on the battleground of Gangs’ Five Points. Over-stuffed with detail it may be – the result of a troubled production – but this is a work whose formal attributes chaotically coalesce after-the-fact in much the same manner as the era on which it casts its eye. MT

A 49-minute oral history, not just of the Scorsese clan, but of the immigrant experience. Familiar faces from their cameo appearances in a number of his films, Catherine and Charles Scorsese take centre stage in their son’s affectionate portrait of a 40-year marriage. Shot in the couple’s apartment, the film’s charm lies in its casual lack of refinement; the gentle ribbing and bickering between the pair as unvarnished as Scorsese’s coaxing of personal and cultural histories. As Scorsese directs his mother in the opening scene – and she directs him back – this most personal of films lays bare the need to preserve such storytelling traditions, as well as the mechanics by which to do so. MT

It’s perhaps surprising that for the most moving and autobiographically probing of his documentaries, Scorsese shares a credit as writer and director (with film critic, Kent Jones). An hour-long tribute to one of his cinematic heroes, A Letter to Elia is no hagiographical love-in. Part confessional, part thematic analysis, part psychological investigation – into both Kazan and Scorsese – the film isn’t shy of confronting the late filmmaker’s personal and political controversies. Ending tentatively with a tribute to a late friendship, the film finally proves itself less a love-letter than a touchingly sincere note of thanks, from one filmmaker to the transformative, soul-piercing work of another. MT

Scorsese’s high society period romance is rarely mentioned in the same breath as his other New York films. Yet in Daniel Day-Lewis’ lusty wannabe aristocrat, Newland Archer, it boasts a sympathetic hero who is in his own foppish way an essential guide to the city of the director’s birth. Jay Cocks introduced Scorsese to Edith Wharton’s source novel in the late ’80s and his old friend was instantly smitten. The resulting script is as faithful as they come; an immaculate literary adaptation that would surely rank higher were it not for the simple fact that Scorsese has so many masterpieces under his belt. AW

Although Silence has been described as the third part of Scorsese’s ‘Faith’ trilogy, the film it feels most akin to is his neglected gem from 1999, Bringing Out the Dead. An Orphean odyssey teetering on the edge of a nocturnal abyss between life and death, night and dawn, the film was the director’s last collaboration with Paul Schrader. You might think a religiously-symbolic, last-ditch grasp towards grace would prove a solemn affair, but this is one of Scorsese’s most blackly comic works, thanks in no small part to Nicolas Cage delivering one of his best performances as God’s Exhausted Man. Directed with hyper-caffeinated, bravura flourishes, the manic energy is tempered by the sense of a waking-dream; that salvation could be on hand, “If I could just close my eyes…” MT

Frank Sinatra’s cover version of the theme song from Scorsese’s 1977 jazz musical – written by John Kander and Fred Ebb and performed by Liza Minnelli – may be more famous than the film itself, but then this is perhaps the most underrated of all the director’s narrative features. An ambitious, over-budget love letter to both the Big Apple and the classic Hollywood cinema of Scorsese’s childhood (its lavish sets were built on the old MGM soundstages), New York, New York is a heady tribute to the outmoded school of filmmaking that gave way to the New Hollywood class who came to dominate American cinema between the late ’60s and early ’80s. Behind the scenes, Scorsese was entering a period of great personal turmoil – brought on by his excessive cocaine use and extramarital affair with his leading lady – that eventually landed him in hospital. An ugly footnote to a romantic, melancholy masterwork that has aged better than many of the Golden Age musicals it riffs on. AW

“Morally offensive” and “theologically unsound” is how the critics (read: Catholic Church) first reacted to Scorsese’s controversial biblical epic. It certainly doesn’t shy away from the serious and – yes – blasphemous nature of Nikos Kazantzakis’ source novel. Shot on a paltry $7m budget for Universal Studios after the project was dropped by Paramount, the film inadvertently marked a watershed moment in America’s culture wars, drawing a line in the sand between the country’s traditionalist values and its increasingly secular entertainment industry. Described in a pre-opening credits disclaimer as a “fictional exploration of the eternal spiritual conflict”, it is first and foremost an allegory of the director’s own crises of faith, most intensely manifested in later scenes where Willem Dafoe’s deeply conflicted, imperfectly human Son of God experiences vivid hallucinations while suffering on the cross. A stirring companion piece to Scorsese’s most recent religious drama, Silence. AW

In reckoning with the profound sin of American genocide – one largely scrubbed from the cultural consciousness – Scorsese shrewdly switches the perspective of David Grann’s source novel to give the Osage Nation a more prominent voice in their own tragic story. Scorsese stalwarts DiCaprio and De Niro are on top form, but it’s Lily Gladstone who delivers the standout performance; a beacon of quiet dignity and hope in the face of persistent colonial tyranny. The film’s disarmingly playful ending, where the director pulls back from the novelistic scope of the central narrative to ask difficult questions both of himself and the audience – pointedly drawing attention to the hypocrisy and complicity that stems from turning such subject matter into popular entertainment – constitutes arguably the greatest masterstroke of his long and storied career. AW

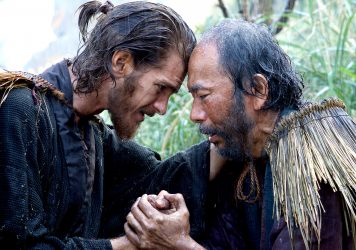

One might argue that it’s a little soon to stake a claim for Silence in the upper echelons of the Scorsese canon. At the very least it is a film that demands repeat viewings. Its long-gestation has been well-documented, and the subject matter should come as little surprise to anyone with even the vaguest knowledge the director’s work; the figures that populate his films live according to a code, and Silence serves as a sustained test of such, a spiritual and intellectual battleground violently physicalised. Whether on the streets of Little Italy, the mountains of Tibet or in late-19th century drawing rooms, Scorsese has proved himself a sensitive and detail-oriented cultural ethnographer. Silence is rooted in such concerns, even as its test of faith transcends questions of religious doctrine to stand for any core, imperilled belief system. MT

Sam Rothstein takes off his over-sized shades, folds his hands beneath his chin and contemplates having arrived right back where he started. Fade to black. Roll credits. Despite being lauded by audiences and critics alike, 1995’s Casino marked the start of an unofficial 14-year hiatus for one of Hollywood’s greatest ever actor-director pairings. It was De Niro who first pitched the idea that would eventually become The Irishman to Scorsese back in 2004, straight after reading ‘I Heard You Paint Houses’, Charles Brandt’s chronicle of the life and (alleged) crimes of Frank Sheeran. The project stalled and the pair went their separate ways before Steven Zaillian was brought in to thrash out a script in 2009. Several more years passed. Pacino joined the cast. Then Pesci. Then Netflix pushed a blank cheque under Scorsese’s nose. Finally, in 2019, with anticipation at fever pitch after more than a decade of speculation and false starts, the director unveiled his suitably epic mob elegy. Boy was it worth the wait. AW

And now, ladies and gentlemen, the man we’ve all been waiting for… Rupert Pupkin is a far cry from the gristly macho archetypes that had by the early 1980s become synonymous with the Scorsese-De Niro double act, but the character is no less compelling – or dangerous – than Travis Bickle and Jake La Motta before him. By turns a(nother) stark examination of masculinity and a scathing celebrity satire, The King of Comedy feels eerily prescient in the way it anticipates of our media obsessed culture – today’s TV landscape is filled with precisely the sort of talentless fame seekers that Jerry Lewis’ veteran talk-show host, Jerry Langford, rails against. Despite being made at the peak of the Scorsese’s powers, the film was a huge commercial flop upon its initial release and the experience took its toll on both its director and star; the pair parted ways only to reunite seven years later for Goodfellas. AW

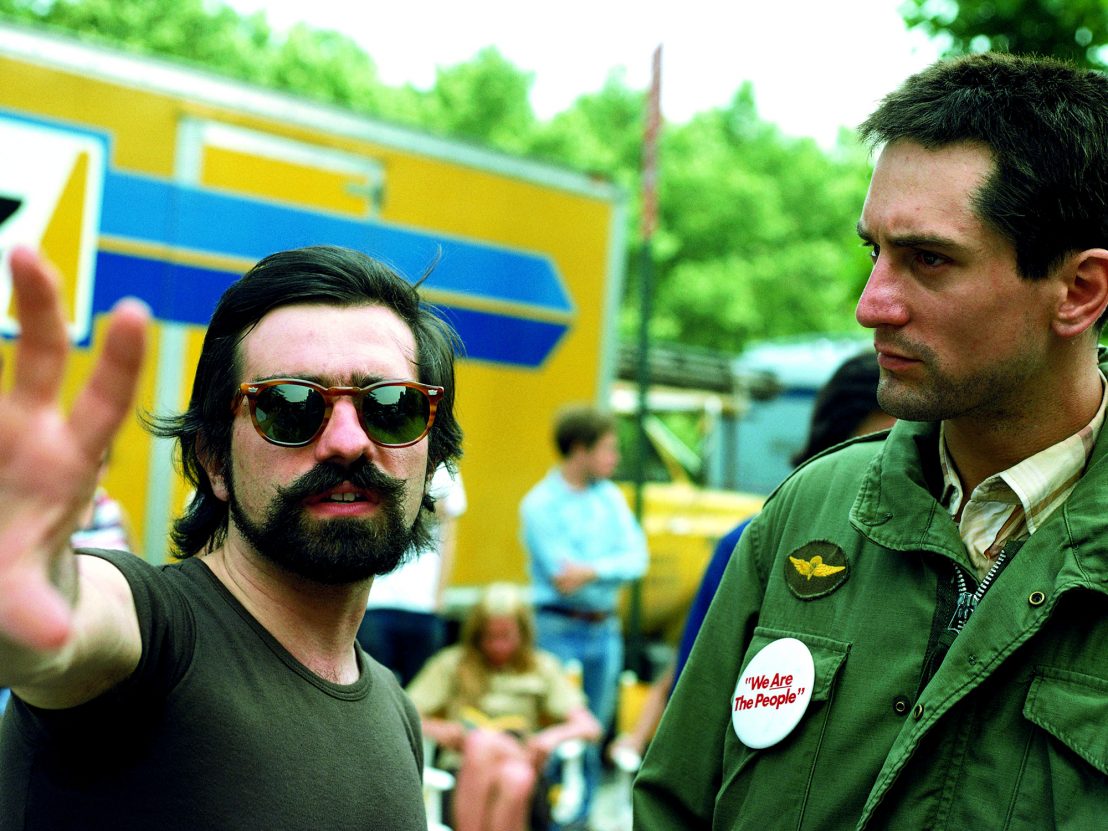

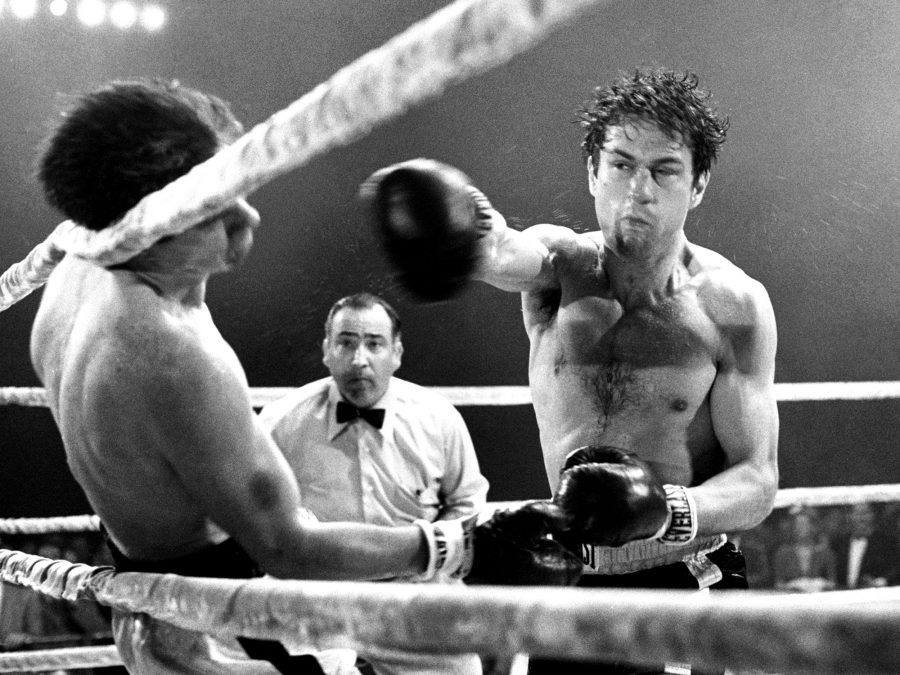

While Scorsese was laid up following a bout of depression that came to a head during the making of New York, New York, he was visited by Robert De Niro, who brought with him a proposition in the form a script about the life of a former middleweight boxing champ. The actor had been obsessed with the (cautionary) tale of Jake La Motta for a number of years, and in his longtime friend and collaborator he saw the only person capable of bringing it to life on the big screen.

It’s fitting that a film detailing the professional highs and personal lows of a brilliant but self-destructive star should put Scorsese – still bruising from the critical and commercial failure of New York, New York – back in the limelight. At the time the director believed that Raging Bull would be his last film, and consequently he put his full creative weight behind the project. It really shows. This is a staggering, virtuoso work whose redemptive qualities cannot be overstated. MT

For a filmmaker’s greatest work – or second greatest, seeing as we’ve set ourselves the impossible task of ranking these films – it might be expected that said film stand as a complete auteurist statement, one undeniably marked with the stamp of its author. That Taxi Driver is a quintessential Scorsese work isn’t in question, but it is a film – perhaps more than any of his others – that couldn’t exist without its collaborators. Not least Paul Schrader, whose particular brand of nihilism deserves equal credit to his director – whether you read John Ford’s The Searchers or Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket as the film’s foremost influence depends on which auteurist lens you favour.

Then, of course, there’s Michael Chapman’s cinematography, running an intoxicating gamut from neon smear to sickly pallor; and Bernard Herrmann’s magnificent (and last) score, which alternately lends melancholy romanticism and an impending sense of dread. Taxi Driver is ultimately a film entirely of its moment, a product of a specific time and place, cast and crew. It may be Scorsese’s masterpiece, but he couldn’t have made it alone. MT

There’s a moment roughly midway through Goodfellas where Henry (Ray Liotta), Jimmy (Robert De Niro) and Tommy (Joe Pesci) stop by the latter’s mother’s house en route to disposing of loud mouth Billy Batts (Frank Vincent). She hasn’t seen the boys in a while and convinces them to stay for a spot of late-night supper. During the meal, Jimmy picks up a bottle of Heinz Tomato Ketchup and rolls it smoothly between his palms in one quick motion, evenly releasing the tangy condiment onto his plate of pasta (as the only non Italian-American at the table, it’s telling that he alone opts to embellish mama’s homemade marinara).

Although this scene was mostly improvised by the cast (presumably to accommodate Scorsese’s elderly mother, Catherine, appearing in a brief but memorable cameo), it nonetheless begs the question: was this specific action described in the script, a subtle yet crucial behavioural trait intended to reveal something about the character’s methodical and clinical nature? Or is it simply how Bobby shakes his sauce? A documentary about the making of the film reveals that it was, in fact, inspired by Jimmy Conway’s real-life counterpart. Still, for all the reasons to love and admire Goodfellas – and there are far too many to list here – it’s small, seemingly arbitrary details like this that make it Scorsese’s most rewarding and rewatchable film. AW

What are your favourite Martin Scorsese films? Share you personal Top 10 with us @LWLies

Published 9 Jan 2017

By Paul Risker

With Martin Scorsese’s seminal crime drama finally out on Blu-ray, we gauge the film’s enduring influence.

Scorsese’s monolithic passion project finally arrives, and it’s a ripped straight from his spiritually devout heart.

By Paul Risker

Silence isn’t the first occasion when the director’s obsession with religion has been at the fore.