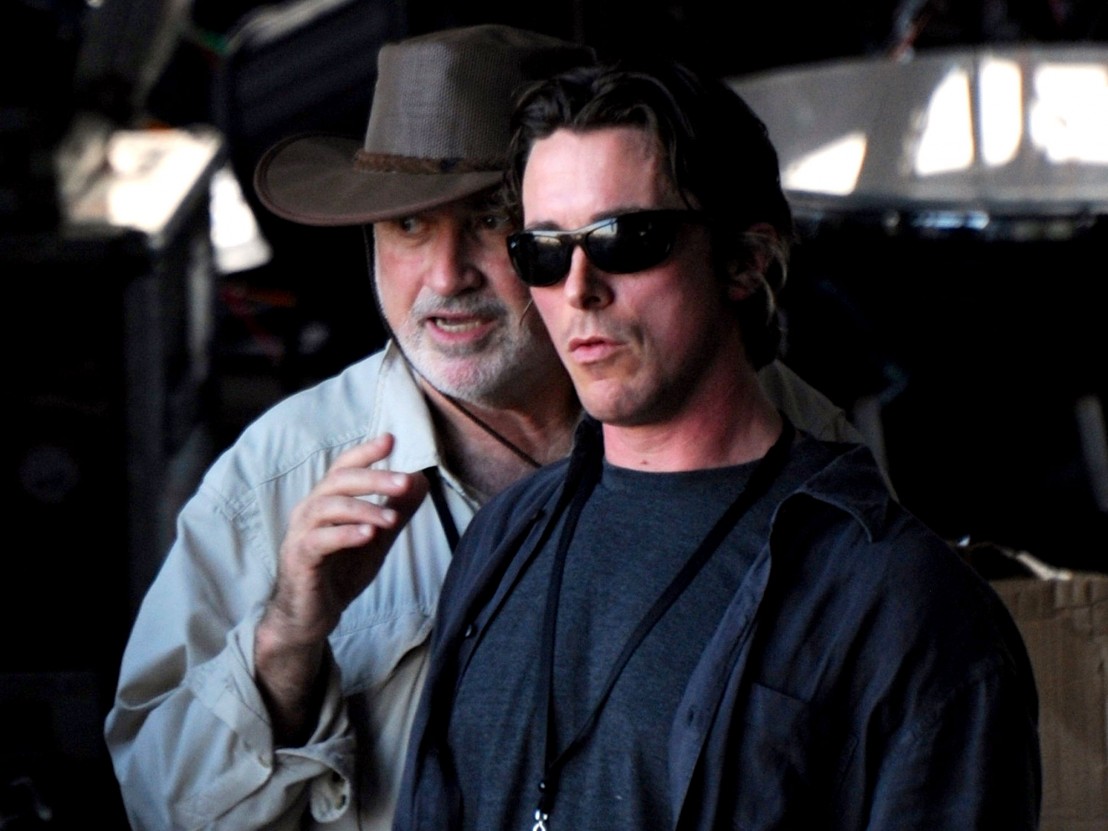

Terrence Malick looks different in person. Without the broad hat, sunglasses, and baggy attire with which he is usually arrayed in the handful of on-set photos which exist online, he cuts a trimmer figure than you would expect. Clean shaven and dressed in a comfortable beige suit, he could pass as Peter Boyle’s little brother. His voice, however, sounds exactly as you would expect it to: warm, slow, ever so slightly nervous. It has softened a bit since his brief cameo in Badlands, but retains a mild twang which betrays his childhood in Oklahoma and his current residence in Texas.

Once you get over the initial shock of seeing one of the cinema’s most elusive figures in the flesh, you are quickly struck by how humble and unassuming Malick is, how gentle and accommodating both his voice and his body language are. Malick is shy, yes, but he is no recluse as is often said, and one imagines that those lucky enough to be welcomed into his inner circle recognise a thoughtful, gregarious, and generous soul somewhat at odds with the image created by the press, who compare him to Bigfoot almost as often as they do other filmmakers.

One such person is Pacho Velez, a documentary filmmaker and Princeton Fellow who arranged for Malick to visit the campus as part of the Lewis Center for the Arts’ Cinema Today series. Velez, who earlier in the day had met and spoken with Malick over sorbet in the student centre, opened the discussion by quoting a passage from Nathaniel Dorsky’s ‘Devotional Cinema’ about the experience of seeing Journey to Italy in the theatre with an audience:

“After the film, the audience entered the elevator in order to descend to the street, and I noticed that everybody was unusually available to everybody else. People had tears in their eyes. Usually the time in an elevator is a ‘no’ time. We either stare up at the numbers or down at the floor, trying to deny the intimacy of the situation. We wait for this ‘no’ time to be over so that we can resume our lives. But in this case everyone was completely accessible and vulnerable to one another, looking at each other, all strangers within the intimate compartment of the elevator.”

Though Malick admitted that “much to our shame,” he and his wife had earlier watched Journey to Italy on a small portable Blu-ray player, he stressed that even just coming into the theatre for the last few minutes of the film reminded him of the affective discrepancy between seeing a film on a laptop or a television and experiencing it projected in a theatre. “They say you look up at cinema, you look down at the television,” Malick said, asserting that for him, going to the cinema involves not simply watching a film, but “looking up in shared awe.”

The director likened the experience of watching movies on a laptop or cellphone to that of seeing the great works of art in the Louvre or the Met reproduced on a postcard, which he referred to as simply “a memento of the experience” of seeing them. Speaking specifically of Journey to Italy, Malick elaborated that while “you would have seen it, you could repeat the dialogue, and it would be the same information,” the film “wouldn’t have its true power on a TV set, and certainly not on a cell phone.”

Despite Malick’s belief that digital means of distribution have been “working against cinema” and “undermining it,” a great deal of the evening was spent discussing how digital cameras have revolutionised filmmaking in general and Malick’s work in particular. Malick, who has shot his last several pictures on a mixture of 35mm, 65mm, and digital formats, said that “digital technology is a lure,” and suggested that the improvisational and impressionistic style which found its fullest flower in last year’s Knight of Cups would have been impossible to realise on film.

Drawing a line between Journey to Italy and Malick’s own work, Velez alluded to Martin Scorsese’s description of the film as having a neutral or absent style in which the audience is simply “following along beside Ingrid Bergman observing her process,” which Velez identified as an antecedent to what he called Malick’s own “documentary interest in the world” and in men and women wandering through it. Malick in turn spoke of the continuing struggle to make scenes feel less theatrical and more “life-like,” to introduce elements of the unknown to keep actors “off-balance” and to, in his words, “catch life on the wing.” Continuing the metaphor, Malick likened those moments to “a quail coming out of the grass;” the freedom afforded by digital cameras, which were neither as time- nor cost-prohibitive as film stock, better allowed Malick and his crew to experiment, eschewing scripts in favour of improvisation and using the camera “almost like a hunter would.”

The downside of this, Malick conceded, is that one tends to become indulgent, drastically overshooting and “losing track over the course of the day” of what’s been done and what’s left to do. When shooting without a script, Malick also admitted, “often you wouldn’t have any good ideas or the actors wouldn’t have any good ideas,” leading to wasted days on location. Worst of all for the director was how laborious the editing process had become. Unlike Badlands, from which Malick estimates he cut only one or two scenes, Malick’s recent films have been whittled down from hundreds of hours of footage, with “most scenes” getting cut completely. It’s become something of a running gag among his actors that they never know until the premiere whether or not they’ll make it into the final cut, but that bemused frustration extends to the filmmaker.

But Malick, having recently finished shooting his upcoming World War Two drama, Radegund, in Germany and Austria, stated that he has “repented and gone back to working with a much tighter script.” He further insisted that “it actually makes it easier to improvise when you have rails underneath you.” Yet despite what he describes as “a serious ambivalence” with regard to digital technologies and their current application in filmmaking and distribution, the overall tone was enthusiastic, with Velez and Malick encouraging members of the audience to share their own experiences shooting films digitally. The directors were particularly interested in hearing how audience members had utilized the GoPro, which Malick had used on Knight of Cups and which he believes will “open the door to a more democratic style of filmmaking.”

Bringing the discussion back to Journey to Italy, Malick likened the impact of digital technology on young filmmakers to that of the Italian neorealist movement upon French New Wave filmmakers like Jean Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut, and their influence, in turn, upon Malick and his peers. The Italian neorealists demonstrated that all you needed to make a picture was “two actors and a car,” and that would-be filmmakers no longer needed to “put in 10 years in the industry and work at the sufferance of a studio.” Now, the ubiquity of digital filmmaking technology has made filmmaking open to “virtually everyone, like writing,” which Malick sees as a good thing. “Aren’t you encouraged?” Malick asked the audience, much of which appeared to be students of the University. “Now the problem is distribution, not production,” a perennial issue, he noted, in all of the arts.

Responding to an audience member who spoke of attaching his GoPro to cars and skateboards as “a poor man’s dolly shot,” Malick elaborated upon the artistic as well as practical virtues of the GoPro, namely that it can go places where a 35mm camera cannot. He recalled an experiment he conducted many years ago with an unnamed cameraman in which the two attempted to find a new way to shoot the interior of a car: “we shot something like thirty angles and all of them were total cliches – you couldn’t find a new angle.” With the “marvelously designed” GoPro, however, Malick found he was able to film his actors from a number of unorthodox angles. The only reservation Malick voiced was the GoPro’s tendency to distort his actors’ faces when used in extreme closeup, owing to the camera’s very wide lens, but qualified it by saying he was encouraged by and impressed with the variety of aftermarket lenses currently being manufactured.

To the best of my knowledge, the only other time Malick participated in an event of this sort was at the Rome Film Festival in 2007, and it was apparent that he has a great affection for midcentury Italian cinema, particularly “from the black-and-white era.” He mentioned I Vitelloni and The White Sheik as his favorite Federico Fellini pictures, with the latter being “one of the funniest films I’ve ever seen.” He spoke nostalgically of seeing these films as a boy in Oklahoma and “coming out into the light and making vows to be a better son or brother, or work harder,” reminiscing how those films – and the experience of seeing them in a theatre – “strengthened you.”

Malick also spoke affectionately of the silent era and made special mention of Ménilmontant, the 1926 Dimitri Kirsanoff short which critic Pauline Kael named as her favourite film of all time. Apropos of his own films’ fixation upon the natural world and their vaguely pantheistic bent, Malick likened silent cinema to a tree that was cut down prematurely, and described Ménilmontant as an indication of how the medium may have evolved had talkies come around ten years later. In an amusing aside, he also expressed his admiration for Joe Carnahan’s Smokin’ Aces, which he described as “quite well directed,” and said he tips his hat to filmmakers who “know how to keep several stories going at once.”

Of course, having released four films in the past five years, with another due in March, one in postproduction and several others in preproduction, Malick seemingly knows something about keeping mutiple plates spinning. When asked what the ending of Journey to Italy meant to him in light of his recent outpouring of work, Malick was coy about his personal drive and philosophy, and about the suggestion that time, its passing, and death – all frequent tropes in his films – weighed heavily upon his thought. Instead, he focused on the bond between George Sanders and Ingrid Bergman’s characters, and the need to recognise and nurture such connections in our lives. “It’s not just death,” but rather the recognition of “how precious love is” and our obligation to overcome our “petty problems with each other” in service of that love. “Some people will find it improbable,” Malick admitted, “but it was quite convincing for me.”

Christopher Bruno is the editor of consideringfilm.com

Published 27 Oct 2016

How has the Illinois native maintained his monumental reputation over the course of his long and elusive career?

A glorious ode to the improbability of existence which asks us to cherish the simple processes of living and loving.

By Taylor Burns

Terrence Malick’s 1999 epic is a stunning meditation on the natural world and our relationship to it.