After years of speculation and hype, the follow-up to Ridley Scott’s chilly cyberpunk classic, Blade Runner, has finally arrived. Yet while original screenwriter Hampton Fancher is listed among the credits for Blade Runner 2049, his former writing partner, David Webb Peoples, is conspicuous through his absence. This doesn’t mean we’ll never see Peoples’ greater vision of the Blade Runner universe though. In fact, we already have in the form of an all-but forgotten 1998 film by British genre director Paul WS Anderson.

Soldier may bear little resemblance to Blade Runner and even less to ‘Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?’, the Philip K Dick novel that inspired Fancher and Peoples. It does not, at least in any obvious sense, represent a continuation of the story in the way that Denis Villeneuve’s new film does. There’s no Rick Deckard, no replicants, no rain-battered cinematography, and no Vangelis’ score. Rather, Soldier can be considered a “sidequel” in that its events take place alongside Blade Runner’s. The film’s only obvious ode to the original can be found in a heap of trash, where observant viewers might spot the metal carcass of a spinner, the vehicle piloted by police officers in Dick’s dystopian metropolis.

But what Soldier lacks in terms of a tangible narrative connection to Blade Runner it makes up for through its thematic kinship. Both films prod at issues of humanity and identity, AI in the case of Blade Runner, and, as you may have guessed from the title, soldiers in the case of Soldiers. Unlike Dick’s replicants, there is no question as to the material nature of Kurt Russell’s titular space marine, Todd 3465. He is made of flesh as his gun of metal. The film begins with his birth and recruitment into Project Adam, an aptly named military programme invested in the creation of a new breed of man, one who executes orders without challenge or hesitation.

Todd isn’t just instructed in marksmanship and athletics. He is taught to watch. Desensitisation to violence is the backbone of his brainwashing curriculum – when other young students avert their eyes from carnage, Todd’s gaze is fixed on the bloodshed. The face is one of the most iconic in American genre cinema, but the eyes are cold and distant, seemingly belonging to someone who has seen hell first hand.

We don’t hear Russell speaks until 12 minutes into the film, and his first word is “Sir!” Only 103 more words leave his mouth in the 87 minutes that follow. That’s a record low for an actor identified as much by his wisecracks as his action chops. Even when playing the stoic, ever-serious Snake Plissken in John Carpenter’s Escape From New York, Russell delivers a string of quippy one-liners. Not so in Soldier, in which most of Russell’s dialogue is strictly affirmative or negative, typically affixed with the appropriate honorific.

Todd may not be a literal machine like Blade Runer’s replicant, but his training reduces him to biological technology, an instrument of a fascist regime that’s like a more straight-faced version of the one in Starship Troopers. As is the case with any piece of technology, a newer, more advanced model (this one even more subservient to the strictures of the system) eventually replaces Todd, who is left for dead on a junkpile of a planet. Todd soon discovers that this world is inhabited by a society of stranded colonists, also abandoned by the authoritarians upstairs.

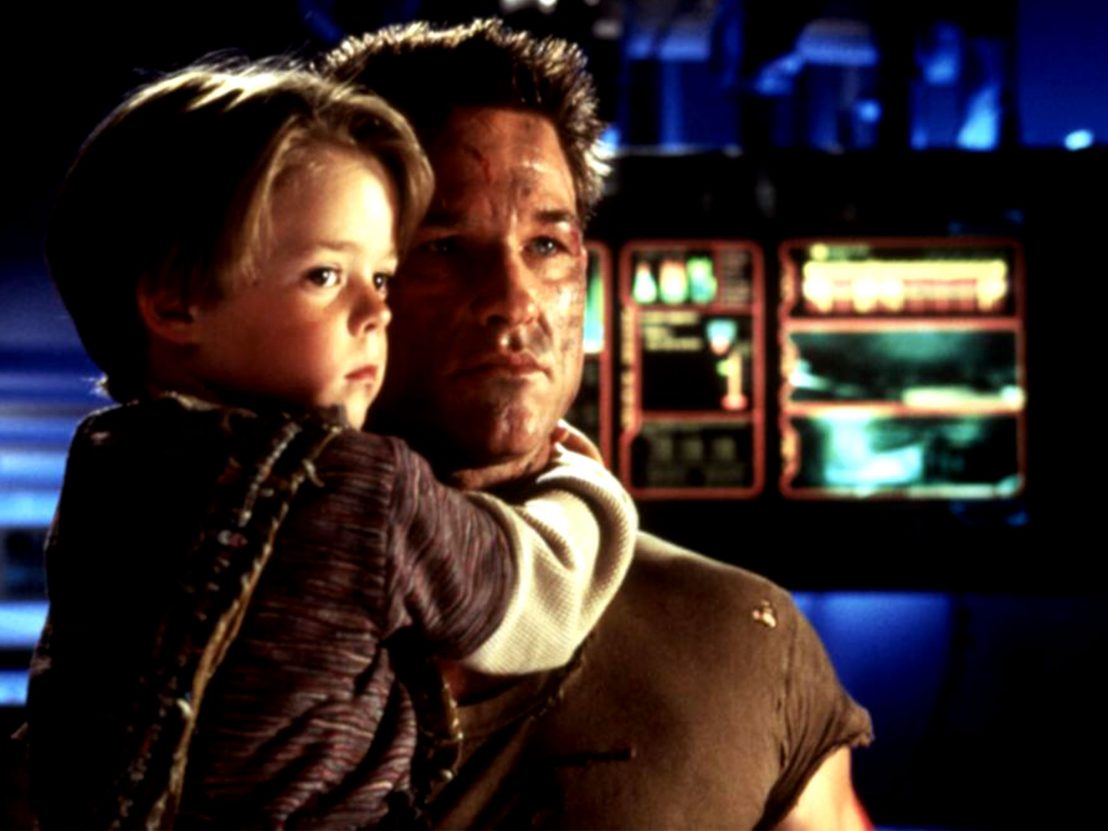

It is in these moments that Russell demonstrates a side of himself he has rarely shown. For the first time in his life, Todd see images of love, not violence, as he integrates into a family with a young boy that in many ways mirrors Todd. That family, and the society around them, represents everything Todd has never had: emotional connection, community and care from other human beings. Todd is a slave to the violent instincts that have been programmed into him, destined to repeat the images he has consumed, but a tenderness and gentleness come across, communicated almost entirely through close-ups of Russell’s face.

In ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, Walter Benjamin writes that fascism is “the aesthetic made political,” an idea that Paul WS Anderson reinforces with a style that prioritises unity and conformity. His tics and trademarks are easily identified: perfect symmetry, one-point perspectives, the God’s Eye view, and a general preoccupation with geometry that has earned comparisons to Fritz Lang and Stanley Kubrick. But as Todd begins to explore the world he’s been dumped on, Anderson’s style loosens. The unintentional settlers of this waste disposal planet live in an almost medieval world of stained glass and kaleidoscopic colours, a sharp contrast from cold blues and greys of enlisted life.

These rainbow-hued sheets of glass are a reflection of Russell’s eyes – two windows into a troubled individual. The military machine has stripped Todd down, beyond flesh and feeling, reducing him to pure movement, a piston in a larger political mechanism: a soldier first, a cylinder second, and a human last of all. By the end of the film, Todd rediscovers his humanity in the community that takes him in. Finally, he knows what it means to possess a soul. In Blade Runner, Scott asks what makes us human? But in Soldier the question is arguably even more relevant: what takes away our humanity, and how can we hold on to it? Only Kurt Russell’s eyes can tell us that.

Published 11 Oct 2017

Denis Villeneuve tangles with Replicants in this bombastic though naggingly shallow sci-fi sequel to Ridley Scott’s 1982 cult classic.

By Alex Hess

The release of Con Air and Face/Off 20 summers ago marked a high-point in mainstream cinema.

Before Blade Runner 2049 hits cinemas, video essayist Luís Azevedo explores a complex existential question.