In January 1977, a historic TV event captivated 85 per cent of the American population: the ABC-TV’s mini-series Roots. Based on Alex Haley’s novel ‘Roots: The Saga of an American Family’, the series starred LeVar Burton in the role of the legendary Kunta Kinte and, for the first time, the story of African-American slavery was told not from the perspective of the coloniser, but through the eyes of the victims of one of the darkest periods in human history.

Though the social climate in the US was slowly shifting at the time, TV networks were still reluctant to air movies and series starring black actors, insisting that white audiences would not tune in. Roots inspired a change in these antiquated attitudes and, most importantly, sparked a global conversation about the history of slavery and its resulting innate racism. Now, 40 years after the release of the original Roots, Kunta Kinte’s story has been remade to appeal to a new generation and, depressingly, its story feels just as urgent now as it did then.

Though the remake follows the same structure as the original series, certain discrepancies in the narrative arc have now been corrected. For example, Kunta’s place of birth, Jufureh, was portrayed as a remote village in the original series when, in actual fact, it was a commercial hub of Gambia, where the inhabitants were principally of Muslim faith.

This is another important aspect of history that has been highlighted in the remake, seeing as many a viewer may not have been aware of how far Islam in Africa actually dates back. A deeper understanding of the Mandinka culture allows the Roots remake to reach a level of accuracy its predecessor never did, not only due to, perhaps, more investigatory resources, but an unedited depiction of white supremacy TV networks wouldn’t risk at the time.

Kunta’s (Malachi Kirby) story begins in Jufureh circa the 1770s, where he is training to become a horse warrior, much like the rest of his family. The initiation Kunta must undergo is physical as much as it is spiritual and, in a sense, it is this spiritual connection to his ancestry, this unbreakable power of the mind and soul, that gives him the strength to survive his bleak future.

This is one of the few glimpses we get into Kunta’s world prior to it changing forever and, even then, the lurking danger of captivity can be sensed throughout, though the anticipated anxiety is somewhat dampened by the royal blue colours of the Mandinka tribe and the warm, African landscape. Kunta and his fellow warriors-in-training are ready to fight the wrongs that have taken over their village and recognise the importance in their mentor Silla’s (Derek Luke) statement: “There is a word for a Mandinka not prepared for battle; it is slave.”

The morbid veracity of the situation doesn’t become entirely real to Kunta until he comes face to face with a dead slave floating along the river in an abandoned canoe. Shocked, he hardly has the time to process what he’s seen before a canoe full of slave traders comes into view, forcing him to go under water and hold his breath until they have passed. Shortly following his initiation into adulthood Kunta tries to convince his parents to let him study in Timbuktu, but his father Omoro (Babs Olusanmokun) insists he stay and honour his responsibility to his family. Angered, Kunta takes off on his horse. This was to become his last day as a free man.

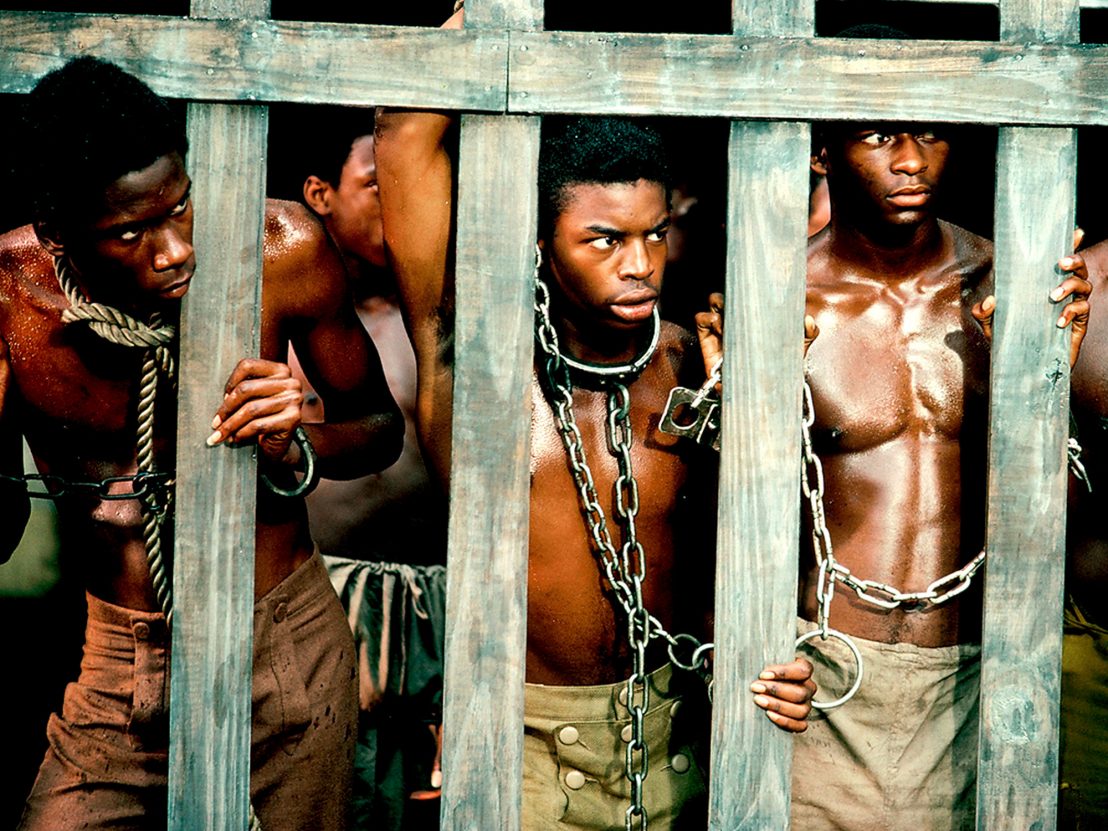

Kunta is captured and finds himself chained in the dark hold of a boat en route to America, where he is to begin his new life as a slave on a tobacco plantation in Virginia. The entire scene is beyond gruelling – it is one that can be felt to your very core and allows many aspects of this sorrowful environment to seep through the screen and into your very living room. It’s claustrophobic to the point in which the viewer can imagine himself to smell the pungent scent of vomit, faeces and sweat, feel the hellish sense of panic, loss and incomparable fear running through the bodies of hundreds of chained men.

Speaking to LWLies, Malachi Kirby describes the experience: “The only time we were on a set, was for the boat scene. It was an actual boat you could have taken out to sea, and they built it to the dimensions that it would have been at the time. They put 150 to 200 African people into this hold and we spent all day in there. I was wearing real chains. The smell you mentioned? That smell was there. It was horrible. There isn’t a lot of oxygen in there because there are so many bodies and there aren’t really windows. You know, a lot of people said they had no idea. They had heard of that form of slavery but they just didn’t know the intricacies of it. And I don’t think that [the new] Roots even shows the depths of it – I don’t know if it’s possible to really depict the depth of that in film genuinely, you know? But I hope that we at least made a good attempt at trying to show a slice of it.”

Episode one of the four-part series focuses entirely on Kunta’s story and his fight to honour his own identity, even as the plantation’s overseer Connelly (Tony Curran) tries to flog it out of him. Though Kunta verbally surrenders to his new given name, Toby, his soul forever honours his birth-name. With the support of the plantation’s fiddler Henry (beautifully portrayed by Forest Whitaker) and Belle (Emayatzy Corinealdi), who would eventually become his wife, Kunta succumbs to but never fully accepts his fate. Kunta passes this incredible willpower and ancestral pride onto his daughter Kizzy (Anika Noni Rose) by teaching her the way of the Mandinkas and it is this wisdom and strength of spirit that gets her through life, even after she is sold to another farm in North Carolina.

Following Kinte’s story all the way up to 1864, Roots introduces a host of characters portrayed by some of the finest young actors working today. Next to Kirby’s emotionally charged and striking central performance as Kunta, Regé-Jean Page’s Chicken George is an absolute delight, offering moments of light-heartedness (cock-fighting aside) amid an otherwise hostile environment.

But what truly sets the Roots remake apart from its ’70s counterpart is the fact that it never shies away from the everyday atrocities African-American people were forced to endure – the bare flesh clearly visible beneath the bloodied lashes in the first episode’s whipping scene being a perfect example. Nor does it aim to soften white guilt by presenting “compassionate” slave masters á la the original’s Captain Davis (Ed Asner). Indeed, it stays true to the historical facts and mentalities in a manner that was deemed too risky in late ’70s America.

The Roots update holds a mirror up to the United States of White America and reflects the past in its present – the world may have changed but the fight is far from over. Kunta and Kizzy are here to serve as a reminder for a new generation to honour identity and the spirit of solidarity amidst a nation still echoing the cries of the past.

Published 9 Feb 2017

By Ashley Clark

One of Britain’s greatest living filmmakers offers an outraged, intense and artful examination of American slavery.

These beautiful, revealing posters highlight African-American culture’s contribution to cinema.

Nate Parker’s much-hyped take on the life of revolutionary slave Nat Turner severely lacks for nuance.