In Orphée, Death rides in a Rolls Royce, served by leather clad bikers; she broadcasts on radio and publishes literary magazines. Jean Cocteau’s bizarre, dreamlike, extremely funny and daringly experimental work took the Venice Film Festival by storm in 1950, and was so popular with audiences upon release that one German cinema showed it every Saturday night for the next 15 years. It continues to influence filmmakers today, with the BFI prepares releasing a new remastered version into cinemas.

In 2004 the critic David Thompson wrote that The Matrix could not have been made without Orphée – and you could now add to that list Inception, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Pan’s Labyrinth and even Netflix’s recent series Stranger Things and Maniac. Filmmakers Chris Marker and Andrei Tarkovsky, in their own eras, both admired the film hugely for its bold retelling of the ancient Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, in which a poet sets off on a journey into the underworld in search of his dead wife.

Cocteau’s masterstroke was to find the contemporary cinematic language for this age-old myth – his underworld exists in the architectural nooks and crannies of the real, entered and exited through mirrors (filmed using pools of mercury). In this ‘zone’ gravity can be upended at a moment’s notice, and people either glide around with ease or struggle as though moving through treacle. “The laws of the other world,” declares one character, “are different to ours.”

Cocteau’s film – which liberally uses negative effects, rewinding, weird cuts and camera angles – is as much about the joyously breakable laws of cinema as it is about the mythical underworld. Tarkovsky’s Stalker, which breaks into colour from black-and-white as soon as its characters enter its mysterious ‘zone’, owes much to Cocteau’s sensibility.

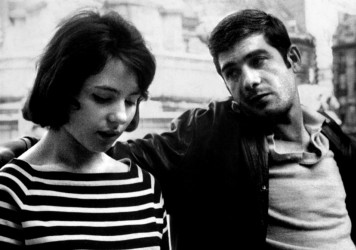

Like Tarkovsky’s zone, Cocteau’s spirit world also has a very modern psychological dimension: it is not just a land of the dead but “a place of men’s memories and the ruins of their habits”. In Maniac (as in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind) Emma Stone and Jonah Hill have to go on the run through the collapsing architecture of their own minds and memories. Likewise Cocteau’s Orphée (played by his lover and long-term partner, the ageing but still ruggedly handsome Jean Marais) is engaged in a battle not just with Death but with his own memories of an impossible love; he can only win through uneasy forgetfulness and oblivion.

Other details blur the lines further between psychology, technology and magic. Throughout the film radio sets suddenly start declaiming fragments of surrealist poetry that Orphée desperately scribbles down – whether they are coming from his own subconscious, or from the spirit world, is unclear.

The disembodied voices over the radio are another part of Cocteau’s influential vision. As with the Nokia phones and blinking green computer screens of The Matrix, Orphée’s supernatural fantasies take place via the normal technology of modern life, making it seem all the more eerily plausible. Just as many a childhood in the 2000s was spent waiting for computer screens to spell out the words ‘follow the white rabbit’, after watching Orphée mirrors begin to seem like ‘the doors through which Death passes’, potential gateways to another world.

The film has its uneven points – Cocteau is certainly more interested in his notions of symbolic and poetic wonder than he is in human relationships – and there are plenty of highly conventional moments of egregious and disturbing sexism. For its cinematic inventiveness and far-reaching influence, however, it is destined to continue finding new audiences.

Published 19 Oct 2018

By Adam Cook

The late French master’s first film, Paris Belongs to Us, is now available courtesy of the Criterion Collection.

The Russian director’s 1979 film is being reissued as part of a new retrospective.

Jean Cocteau’s ravishing and erotic masterwork is restored as part of BFI’s huge survey of Gothic cinema.