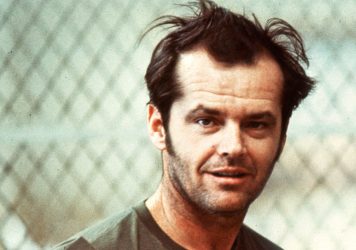

Jack Nicholson ended the 1980s with his reputation as one of the biggest stars in Hollywood in tact, stealing the show in both George Miller’s The Witches of Eastwick and Tim Burton’s Batman. Then the early ’90s brought back-to-back flops in the shape of Chinatown sequel The Two Jakes and messy romantic comedy Man Trouble. Despite this, Nicholson still had enough clout to secure a $10 million dollar payday and a Christmas release date for his next leading role – but he desperately needed to deliver another big awards-worthy performance.

It was with added interest, then, that he took on the part of Jimmy Hoffa in the 1992 biopic of the infamous labour union leader. Set on 30 July, 1975 – the date of his mysterious disappearance – and told via a series of flashbacks, Hoffa boasted a sizeable budget ($50 million), a screenplay by David Mamet, and was directed by one of the hottest talents around, Danny DeVito.

For those only familiar with DeVito’s more recent output, the idea of the Trashman directing Oscar-bait must seem ludicrous. But DeVito’s career behind the camera was on the rise at the turn of the 1990s thanks to the success of his first two features Throw Momma off The Train and The War of the Roses.

The New York Times declared him “the new Robert Redford”; Joe Roth, former head of 20th Century Fox’s film division, went as far as to put DeVito in the same league as Francis Ford Coppola, telling the LA Times, “directing movies is in his blood.” DeVito seemed to buy into his own hype, telling the same paper, “it’s like I’m in the middle of the square with this big slab of marble and the Medicis say, ‘Look, we could’ve given this to Michelangelo or Da Vinci. But we’re gonna let you take a whack at it instead.’’’

With Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman fast approaching, now seems as good a time as any to reflect on DeVito’s transition from comedic actor to major filmmaker and to reevaluate a film which was billed as a comeback vehicle for Nicholson but wound up meeting a similar grim fate as its subject.

While Hoffa was first portrayed on screen in 1983, when Robert Blake played him in the TV movie Blood Feud, plans of bringing the fiery public figure to cinemas were in place as early as 1961. According to a piece in The Independent in The Independent, 20th Century Fox producer Jerry Wald was keen to adapt Robert Kennedy’s 1961 novel ‘The Enemy Within’ (which we see Nicholson reading at the film’s climax), with On The Waterfront screenwriter Budd Schulberg hand-picked to provide the script.

But before production got underway, the studio pulled out, with Schulberg stating, “a Teamsters’ henchman walked into the studio chief’s office and announced that, if the film was produced, drivers would refuse to deliver prints to cinemas, and any audiences would be driven from their seats by stink-bomb attacks.” Interest from Columbia Pictures shortly after was quickly dwindled due to actions from Hoffa’s lawyers.

Almost three decades later, Joseph Isgro, a highly successful music promoter with ties to organised crime, was approached by Frank Ragano, a former lawyer for Hoffa, and Brett O’Brien, son of Hoffa’s adopted son, Charles “Chuckie” O’Brien (played in The Irishman by Jesse Plemons). They wanted Isgro to fund a movie based on Hoffa’s life, and he agreed. “I really identified with Hoffa’s plight,” Isgro told the LA Times in 1993. “He had a lot of run-ins with the law and I could relate to the kind of government pressure he was subjected to.” Isgro was charged and indicted on over 50 counts of racketeering, mail fraud and other payola-related crimes in 1989, all of which were dismissed.

Robert Moore, author of ‘The French Connection’, penned a screenplay based on Chuckie’s time with Hoffa and separate interviews with other Hoffa associates, but the deal unraveled because, according to Isgro, Ragano and O’Brien did not possess the rights to show Hoffa’s life on screen. So the promoter made a separate deal, causing both Ragano and O’Brien to sue Isgro (both cases were later settled).

Isgro sold his version of Hoffa to producer Andrew Pressman, who brokered a deal with 20th Century Fox. Pressman was unsatisfied with Moore’s draft and reached out to Mamet, fresh off directing his debut feature, House of Games. Pressman was unsure he would be able to get Mamet on board, but being the son of a labor lawyer he jumped at the chance to write a film about Hoffa.

Once Mamet’s script was complete, the studio approached a host of directors including John McTieran, Oliver Stone and Barry Levinson. According to Dennis McDougal’s book on Nicholson, ‘Five Easy Decades’, DeVito first heard about Hoffa during lunch with Roth before a trip to Europe. When Roth mentioned a script based on Hoffa’s life was in development, DeVito immediately expressed interest, only to return to Hollywood and learn that Fox had already offered the job to Levinson. “I start screaming and yelling,” he tells McDougal, “especially when I hear that Barry Levinson was at some [expletive] party and when he said he was interested in the script, they sent it to him!”

In the midst of his rage, DeVito received a call from none other than Levinson, who wanted to talk about Tin Men, the 1987 film which he directed and DeVito starred in (which happened to be playing on television). DeVito, nonchalantly, requested to take a look at Mamet’s script, but Levinson informed his friend that he was reading through it and expressed his admiration for Mamet, seemingly dooming DeVito’s chances. Luckily for DeVito, Levinson eventually stepped aside.

As for who would play Hoffa, Pressman had two actors in mind: Robert DeNiro, and the actor who would end up playing him 27 years later, Al Pacino. Both passed on the role. DeVito only saw one person playing his and Mamet’s version of Hoffa. “[Nicholson] knew I had the script in ’89, and I really bothered him about it,” DeVito recalls in McDougal’s book. Growing impatient at Nicholson’s reluctance to consider the part, DeVito decided to take matters into his own hands, sneaking into Nicholson’s estate at night, script in hand, and waiting outside his window. “He opened the curtains of his house in Los Angeles one morning; he looks down, does a double take, and I’m standing there asking and begging.”

Nicholson took the part, wearing a prosthetic nose, hairpiece and fake tooth to more closely resemble Hoffa, and, like Pacino, listening to recordings of Hoffa in order to fully immerse himself in the character. It’s said that Hoffa’s own son did a double take when he visited the set and saw Nicholson dressed like his father.

The film’s harshest critic was Ronald Goldfarb, Bobby Kennedy’s colleague in the US Justice Department, who called the film “total trash”, condemning it for portraying his former boss as a “wimpy, nerdy, spoilt brat.” Hoffa’s son also didn’t approve, stating in no uncertain terms, “I didn’t like [the film]; they didn’t depict who he was.”

Critical reviews of the film were mixed. Owen Gilberman of Entertainment Weekly called it “turgid” and described Nicholson’s performance as “all swagger and no depth.” Desson Howe of The Washington Post called Hoffa, “the emptiest prestige picture of the year.” The film had its defenders, mainly Roger Ebert, who wrote that the film, “shows DeVito as a genuine filmmaker.” Vincent Canby of The New York Times, praised it for delivering, “a bitterly skeptical edge that is rare in American movies.”

Hoffa did receive two Oscar nominations, for Stephen H Burum’s cinematography and Ve Neill’s makeup work, but it was a box office bomb, grossing a measly $6.6 million dollars on its opening weekend and ending up with a total of $35 million, a $15 million loss. DeVito went on to direct just a few more features, including the cult classics Matilda and Death to Smoochy, while the big awards-worthy performance Nicholson was looking for arrived in A Few Good Men the same year. In Patrick McGilligan’s biography of Nicholson, he writes of the actor’s disappointment with how Hoffa turned out: “Nicholson believed he had scored another touchdown [but] Hollywood had moved the goalposts past him.”

Both Nicholson and Pacino deliver chest thumping performances, exuding a take-no-prisoners attitude that was synonymous with Hoffa himself. However, the main reason why Pacino’s take on Hoffa will soon eclipse Nicholson’s in the public consciousness is that the Jimmy Hoffa we see in The Irishman is more than the guy “with the biggest balls in the room”, as DeVito once said. Pacino’s Hoffa loves ice cream as much as he hates the Kennedys, has zero tolerance for tardiness (regardless of traffic), and is shown to have an off switch.

Scorsese and Steve Zaillian show Hoffa away from the cameras, his followers, and his enemies. We see him as a father figure, a friend, as a regular person, rather than just an icon of American manliness that Mamet, DeVito and Nicholson presented in 1992. While Pacino’s performance will likely endure, Nicholson’s has already been resigned to the margins of film history.

Published 7 Nov 2019

By Sophie Yapp

There’s never been a better time to revisit Danny DeVito’s cult comedy.

By Sophie Wyatt

On the occasion of Jack Nicholson’s 80th, the BFI give this tragicomic classic another big screen run out.

By Anton Bitel

The actor delivers arguably his finest hour in Hal Ashby’s The Last Detail.