Though primarily known for his visceral horror films, Italian maestro Lucio Fulci worked across many genres. Beginning with a range of comedies in the 1960s, the director’s 50 or so films left few genres untested. Undoubtedly, his work in horror defined him, causing mayhem and controversy in a range of fantastic films, from splatters like Zombie Flesh Eaters and The House by the Cemetery to dark, psychological terrors such as A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin and Don’t Torture a Duckling. This, however, wasn’t all Fulci was capable of.

Though horror seemed to bring out the best and most lurid of his filmmaking capabilities, Fulci also showed prowess in the western (more specifically, the Spaghetti western). Fulci made just five films in the genre and, even then, two are them are very loose interpretations of what constitutes a western. Yet they showcase another side to the director’s talents and deserve greater recognition in his body of work.

Massacre Time, also known as The Brute and the Beast, was Fulci’s first western and shows the penchant for violence that would characterise his later work. Following the battle between a ranch and a prospector (played by Franco Nero in the same year he first played Django), Massacre Time is incredibly violent for a 1966 western and must have shocked, even in a post-A Fistful of Dollars world. As Fulci himself once famously suggested, “Violence is the Italian art!” and so Italian westerns had a national interest in pushing things further than their American counterparts.

Some of Massacre Time’s action has the sort of fantastical absurdity that would later be satirised in films like Enzo Barboni’s They Call Me Trinity. Characters front-flip through the air and shoot with alarming accuracy in the most enjoyably stylised fashion. Yet such style is coupled with Fulci’s determinedly gritty approach to violence more generally. Violence is far from clean-cut in Fulci’s cinema and his westerns are no different. In fact, Fulci saw the film as different to other Italian westerns of the age, telling Starburst Magazine in 1982 that it was a “fantastique” and had a duality of tone, “both soft-spoken and extremely violent.” The switch between these tones makes a first viewing especially effective, with its jolts between mood exhilarating.

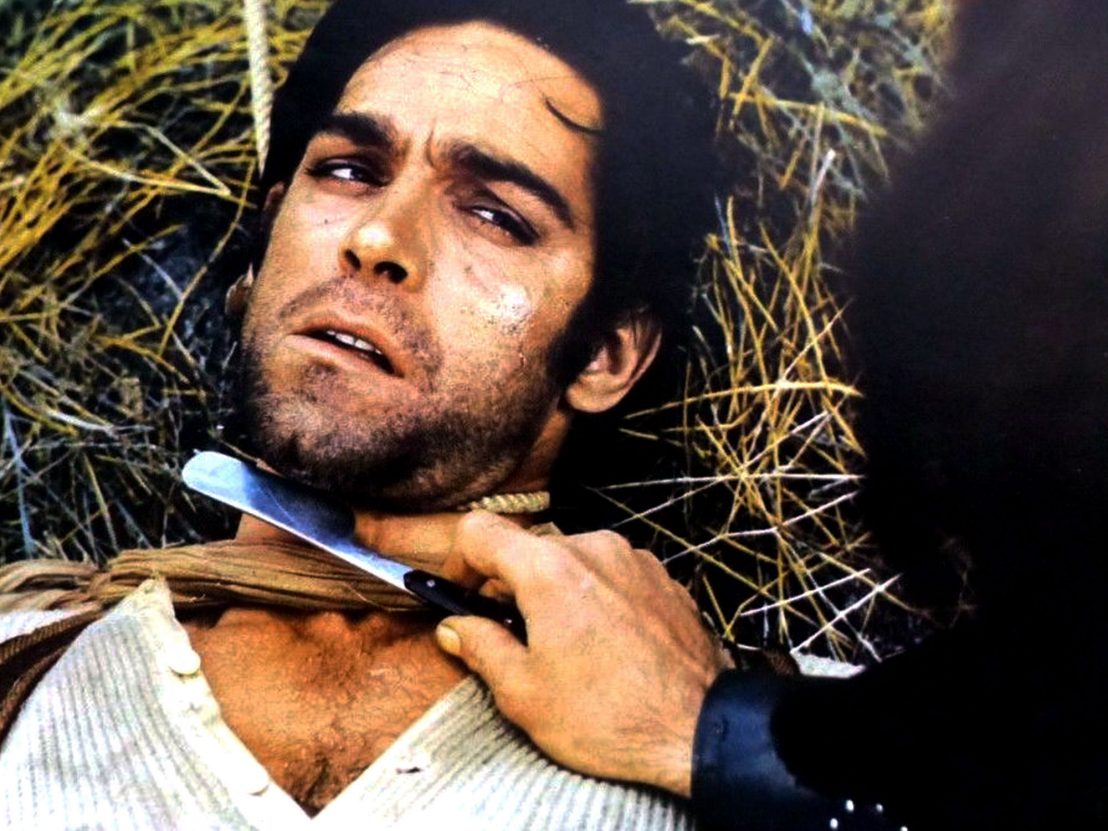

If Massacre Time’s narrative is simplistic, it is deliberate so to emphasise the characters’ determination in the face of increasing levels of plight. The film has two real centrepieces that are built towards: its final shootout (as per usual in this particular brand of western), and the violent fall of the main character at the two-thirds mark. The latter sequence is especially accomplished, with the prospector’s public lashing at the hands of Junior Scott (Nino Castelnuovo) highlighting the precise visual language wielded by Fulci. The sequence is extended and lingering, each whiplash utterly agonising. Nero’s character is even kicked into a fire, as if each particular instance of pain just isn’t quite enough. He must be totally broken before he can rise again.

Fulci returned to the genre in the ’70s with a run of westerns. In 1973, he began one of the strangest minor trends in Italian Cinema: the White Fang films. Based (increasingly loosely) on Jack London’s 1906 novel following the heroic dog of the title, as well as cashing in on the recent success of Ken Annakin’s adaptation of The Call of the Wild, Fulci directed the opening two films of the three: White Fang and The Return of White Fang. Though not strictly westerns, their settings, characters and style does conform to the genre’s tropes. Both starred Franco Nero again (as well as the excellent John Steiner as the villain), the ending of the first film is a dynamite-filled shootout at a dam, and the shenanigans of the sequel fulfil most of the requirements of the typical “fight for a goldmine” western narrative.

What makes these weaker films entertaining is the sheer fact that Fulci was trying to, on paper at least, make a series of family films. It’s unsurprising to find the director unsuited in the most amusingly inappropriate of ways. The violence in these films is still shocking. Bodies are buried in trees, wounds are severe and gaping, the eyes of the dog are gouged out by eagles and bears respectively, and the general narrative is one that consistently requires violence to continue its flow. It makes for two remarkably odd films whose inappropriateness for their intended audience is, in hindsight, part of their charm.

If Fulci’s take on the western had a highpoint, then it undoubtedly occurred the year after his last White Fang film, when he made the astonishing The Four of the Apocalypse…, loosely adapted from a Bret Harte short story. The film’s biblical atmosphere is heady and dizzying as we follow four down-and-out lowlifes led by Fabio Testi trying to outrun trouble, mostly in the form of a sadistic outlaw called Chaco (Tomas Milan). The film’s style is dramatically different to most Spaghetti westerns around it, feeling at times closer to films like Clint Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter or even Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo.

Fulci’s film may be one of the most brutal and sadistic westerns ever made, more like Cormac McCarthy in ‘Blood Meridian’ territory than anything else. Chaco’s character was based loosely on Charles Manson and there’s something of the collapsed hippy dream in his mixture of roguish charm and utter sadism. Never trust a man with crosses under his eyes. In a prolonged sequence of rape and torture, Chaco drugs the group of four with psychedelics, rapes Bunny (Lynne Frederick) and torments the group, having not been content with flaying a man strapped to a tree moments before. It’s in strange halfway realm between the psychedelic and the Old Testament, a nightmarish vision of a hopeless Utah that turns into a typically effective ’70s revenge film with a satisfying pay-off.

One interesting aspect that runs as a strain throughout all of Fulci’s westerns is how heavy violence feels. When bullets collide with chests and limbs, the wet slap of their impact feels more grittily realistic than the shootouts generally found in the era’s westerns. As in his later Horrors, injury for the most part is shown to hurt. The violence of The Four is especially visceral, and yet is filmed with precise composition that understands the placement of the body in the landscape; the dirt under the nails that Italian westerns generally had such dexterity in conveying.

In his last western before committing almost completely to horror, Fulci reminded viewers that the western could still be a vehicle for drama as well as violence and thrills. Silver Saddle was made in the dying days of the genre as horror truly took precedent and the ’70s turned to the ’80s. The film follows a bounty hunter (Guiliano Gemma) whose violent past hides secrets. By chance, he is forced to protect the son of the family whom he loathes; his own descent into violence initially caused by an early member gunning down his father before he committed his first act of killing in revenge when only a child.

Fulci made the most of things in his final western, in particular in the film’s action sequences which again add a bloody reality to the more flamboyant shootouts. If the film is a step down from The Four, it’s because of that film’s strengths rather than any inherent weakness of Silver Saddle (that is besides its structure which fires its load of action a little too early). It’s certainly hard not to love a film whose main characters are called Roy Blood and Snake (Geoffrey Lewis).

Some of the film’s visuals are especially magnificent, even painterly. One sequence, when Snake is searching the dead of an attacked stagecoach in the middle of a vast panorama, is as beautiful as anything in more respected films of the genre and era, and cinematographer Sergio Salvati produces some of his finest images before committing with Fulci to the filming of the rotten walking dead.

Fulci’s westerns showcase a director who could confidently move between a range of genres, whatever the circumstances. The interest in these films is two-fold; in how distinct they feel to other films in the genre and how they show the early rumblings of a director soon to find confidence in his pulpy, hyper-violent voice. On the one hand, they feel unique in their blending of typical Spaghetti western themes and visuals with a director’s growing sense of personal interests. On the other, they pre-empt the films that would follow, hinting at the even gorier pleasures the director would find himself creating in the years after the dust of the Spaghetti western had firmly settled.

Lucio Fulci’s Massacre Time is being released as part of a limited edition Blu-ray box set, ‘Vengeance Trail’, by Arrow Video on 26 July.

Little White Lies is committed to championing great movies and the talented people who make them. But to keep going, and growing, we need your support. Become a member today.

Published 25 Jul 2021

By Adam Scovell

Throughout the 1970s an exciting subgenre dominated Italian cinema, combined action and crime to dizzying effect.

The screen icon talks Tarantino, the delayed Django Lives!, and the time he got naked for John Huston.

By Anton Bitel

The visionary Italian director’s 1981 film The Beyond remains one of his most unnerving, transgressive works.