A procession of cars move slowly past a restaurant where gangster Tony Camonte (Paul Muni) is flirting with his love interest Poppy (Karen Morley). The passengers of those cars open fire with machine guns, wreaking havoc in the building with round after deafening round forcing Tony and his companions to take cover. Most people would stay rooted to that spot when faced with such an onslaught. But Tony is no ordinary gangster. “Hey look,” he exclaims, “They got machine guns you can carry!” before proceeding to stand up, fire back, and collect the loose weapon of a dead man like a child who has just opened a surprise birthday present.

It’s a scene that is both shockingly violent and unsettling for its brazen casualness – especially so for a film released way back in 1932. Even next to other gangster films from the ‘pre-code’ era, like Little Caesar and The Public Enemy, Howard Hawks’ Scarface, the story of a rogue (clearly based on Al Capone) instigating gang warfare, was scandalous. The censors demanded rewrites that more explicitly condemned Tony, including the addition of a title card that read ‘Shame of the Nation’ plus an opening message stating: ‘This picture is an indictment of gang rule in America.’

But the piousness of these additions couldn’t help but sound arch and sarcastic when juxtaposed with the rest of the film’s gleeful violence. The weapon of choice for most of the gangsters is the Thompson submachine gun (the lightweight firearm Tony is excited about being able to carry), and it is fired at an excessive cadence at an ear-shattering volume. It’s not just the violence that was taboo either – Hawks and producer Howard Hughes even managed to get away with barely concealed allusions to incest, as Tony becomes jealous of anyone who dares to romance his sister Cesca (Ann Dvorak).

The extremes of Scarface was pushed even further in Brian De Palma’s Al Pacino-starring remake in 1984, but it’s in the gangster films of Martin Scorsese that its legacy is most keenly felt. Scorsese has come to virtually define the gangster genre through films like Mean Streets, Goodfellas and The Departed, and all owe a debt to Scarface. They are similarly punctuated by extreme violence; for instance the much-lauded single take of Henry and Karen entering the Copacabana in Goodfellas has the same fluid quality of the technically bold three-minute opening shot of Scarface, which tracks in and out a building where Tony claims his first victim. More explicitly, The Departed see Scorsese employ the recurring ‘X’ shape that lurks surreptitiously in the frame whenever someone’s about to be killed – a striking visual motif that appears as everything from the shadow of a road-sign to the strapping of a woman’s dress.

Another parallel to Scorsese is the way Scarface boldly combines its violence with humour. Narrating the documentary ‘A Personal Journey Through American Movies’, Scorsese comments on how Hawks, “was as much a master of comedy as a master of action,” and that the film is “at times… very funny.” Indeed, what makes the drive-by shooting scene especially disarming is that the violence is used to further a gag about Tony’s useless secretary (Vince Barnett), who is unable to successfully take down a message for his boss throughout the film, unable in this instance to hear what is being said down the other end of the line over the cacophony of bullets. In another scene he has to be held back from shooting the phone when the caller frustrates him, an absurdly futile gesture that hilariously demonstrates how the only resolution to problems these gangsters know is violence.

This darkly comic tone doesn’t take the edge off the violence, so much as it fronts up about the fact that there can be an indecent thrill to watching onscreen violence, and provocatively indulges in that thrill. “That world was almost attractive because of its irresponsibility,” Scorsese has said, “And that was disturbing” – a description that just as accurately applies to his own gangster films.

But perhaps the main precedent Scarface set was the allure of its dangerous protagonist. Scorsese has revealed that his fondness for Tony lies in the fact he is a “fierce man” and yet “you really like the guy. He’s dangerous, but you actually love him.” He’s suave, well-dressed, vain (the first time we encounter him properly is him getting a massage), cool, wise-cracking, ambitious and has an impudence towards authority that can’t help but be beguiling. Put simply, he is just like the anti-heroes of Scorsese’s work. Indeed, the director even explained, “That’s the same thing I tried to do with the main characters in Goodfellas.” It’s safe to say he succeeded in that sense, so too that he may never have done so without the blueprint set by Hawks’ astonishing film.

Published 4 Jan 2017

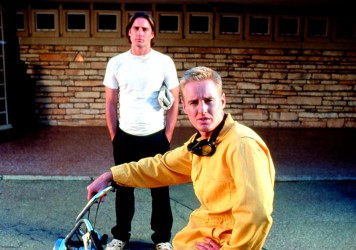

Wes Anderson’s brilliant debut, which turns 20 this month, channels the youthful spirit of Mean Streets.

By Jen Grimble

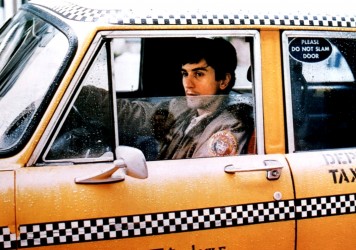

How a 33-year-old Martin Scorsese shook the film world when he brought his nihilistic neo-noir to Cannes.

By Paul Risker

Silence isn’t the first occasion when the director’s obsession with religion has been at the fore.