The practice of constructing languages harks back to the 12th century, but thanks to J.R.R. Tolkien’s fictional languages in the world of Middle-earth, many people took up the pastime in the 20th century. The release of The Lord of the Rings and the appendix that included Tolkien’s created language notes brought greater visibility to conlanging (the creation of constructed languages). David J. Peterson, the man who famously created the fictional languages Dothraki and Valyrian for Game of Thrones, spoke to LWLies about the art of language creation for film and television.

LWLies: Did you always see conlanging as a viable career path?

Peterson: It’s not something you could have decided to do professionally in the past because the job didn’t exist. Before 2009, there had been a few instances where people had been paid to create a language, but that was it.

I’d been creating languages on my own for ten years before getting into it professionally. When I spoke to other conlangers, it seemed unlikely that anyone would ever be paid to create languages because nobody had ever been hired to create a language because they were good at it. The only people who were hired to create languages at that point were randomly on set at the time, people with linguistics degrees, or in one case, a graduate student whose website featured a sentence in Klingon (a constructed language spoken by the Klingons in Star Trek).

You’ve created over 60 languages at this point. When you’re developing fictional languages, do you ever get concerned that they are going to sound similar?

I don’t worry about it too much. We have all these different sounds in the languages we speak on Earth and many, many more. No language on Earth uses all of them — or even a quarter of them. But they’re so different right?

The problem is that when you’re creating languages for TV and film, the producers often say they want the language to sound unique, but it also needs to be easy for the actors to pronounce because they’re often monolingual English speakers.

This means you’re stuck with sounds from English or Western European languages that they’d be familiar with, which is a small subset of the sounds. But you can make things sound quite different by changing the phonotactics, or in other words, the rules of how the sounds of a language are put together, including the intonation and stress patterns.

What does the process of creating a spoken language involve?

After figuring out what the language is going to be used for, I start with the sound system. Then, I move on to the grammar of the nouns, verbs and other parts of speech. I usually start with nouns because they are more stable. Verbs tend to be more difficult. As you move on to each different stage, it sometimes triggers the revision of a previous stage.

Once I have the parts of speech, I can move on to phrase structure and sentence structure, which involves different sentence types, like questions or sentences with relative clauses or subordinate clauses. Then you go to the dictionary and start creating words. The most important part is the grammar, but the longest part is creating words so that they look like they belong. Imagine translating into another language, knowing that the words you need to translate don’t exist in that language.

Do you tend to base your constructed languages on existing languages?

We have two different types of created languages that we distinguish between — a priori and a posteriori. With a priori languages, the grammar and lexicon are entirely novel. A posteriori languages are based on something existing. For example, when I was creating a language for The 100, an American sci-fi TV drama series about Earth after a massive nuclear catastrophe, I had to create a language for fictional people in the real world. For that reason, they spoke a descendant of a real-world language. It’s the American English of the future. Every word of the language and every part of the grammar came from modern English.

In the case of high Valyrian in Game of Thrones, this is a totally fantasy world that has no connection to our world. So why would any of it be based on any language that exists in our world when none of those languages are supposed to exist there?

How do you focus on developing the right parts of the language for the production you are working on?

If the grammar is pretty much settled, but you haven’t got the scripts yet, then you need to anticipate the kind of vocabulary you’ll need. In some cases, like Game of Thrones, I mostly knew what scenes were coming because I was able to refer to George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire books, which Game of Thrones is based upon.

For example, I knew the general direction of the story of Daenerys, one of the protagonists in the series, because of the things she does in the books. So, I could imagine what types of things the Dothraki might say and create the vocabulary I thought I’d need ahead of time.

What sorts of language creation briefs do you tend to receive before you start working on a production?

Game of Thrones was a little different because the producers contacted the Language Creation Society and there was a competition. Most of the time, though, there’s a short conversation with production to make sure we’re on the same page. It’s usually about sound because they don’t care about grammar. They listen to a sample of the language and tell us what they think. Sometimes, there’s some back and forth, but then it’s just on me — or me and my partner/fellow conlanger, Jessie Sams.

Do you do language classes with the actors or do they just get the script?

It has worked both of those ways, depending on the production. For Game of Thrones, I never worked with the actors, but the best performance I have ever seen by somebody working with a created language was on Game of Thrones. That performance was by Jacob Anderson, who played Grey Worm. What he had to do in episode 305 was very difficult because he had quite a long speech, and those were the first spoken lines that his character had at all. It was really rewarding to watch.

What’s the wackiest request you have received when creating a language for a production?

Dan Weiss, one of the co-creators of Game of Thrones, asked me to translate the “French Taunter” dialogue from Monty Python and the Holy Grail for Season 4. They were like, “Daenerys is going to be having a conversation with her people and on the other side, there’ll be this guy shouting at her.” Weiss wanted to have him saying this, with no subtitles.

And how did you go about creating the different variants of Valyrian in Game of Thrones, such as Astapori Valyrian?

Astapori Valyrian is an a posteriori language; it is an evolved form of High Valyrian that has a lot of influence from the former Ghiscari language, which was spoken in the Ghiscari Empire that existed before the Valyrian Empire destroyed it in Game of Thrones.

Basically, when you’re creating a language like this, you start by creating a daughter language. For example, if you look at the transition from Latin to Spanish, over time, the sounds, the meanings of words and the grammar changed.

I started with High Valyrian, with the knowledge that these elements were going to change. The extra consideration was that the High Valyrian language displaced an older fictional language — Ghiscari. The sound system in Ghiscari helped to influence what sort of sound changes were applied to High Valyrian to produce Astapori Valyrian. I made a profile for the Ghiscari language, based on the Ghiscari names in the books.≈

Did you expect Valyrian and Dothraki to get the reception they have got from audiences?

Valyrian has had a pretty big reception. The return of the drama series House of the Dragon really helped with that. I was able to create a Valyrian course for Duolingo, too. For Dothraki, it’s been a much slower build. At its height, I had about six people interested in learning Dothraki.

What are you working on at the moment?

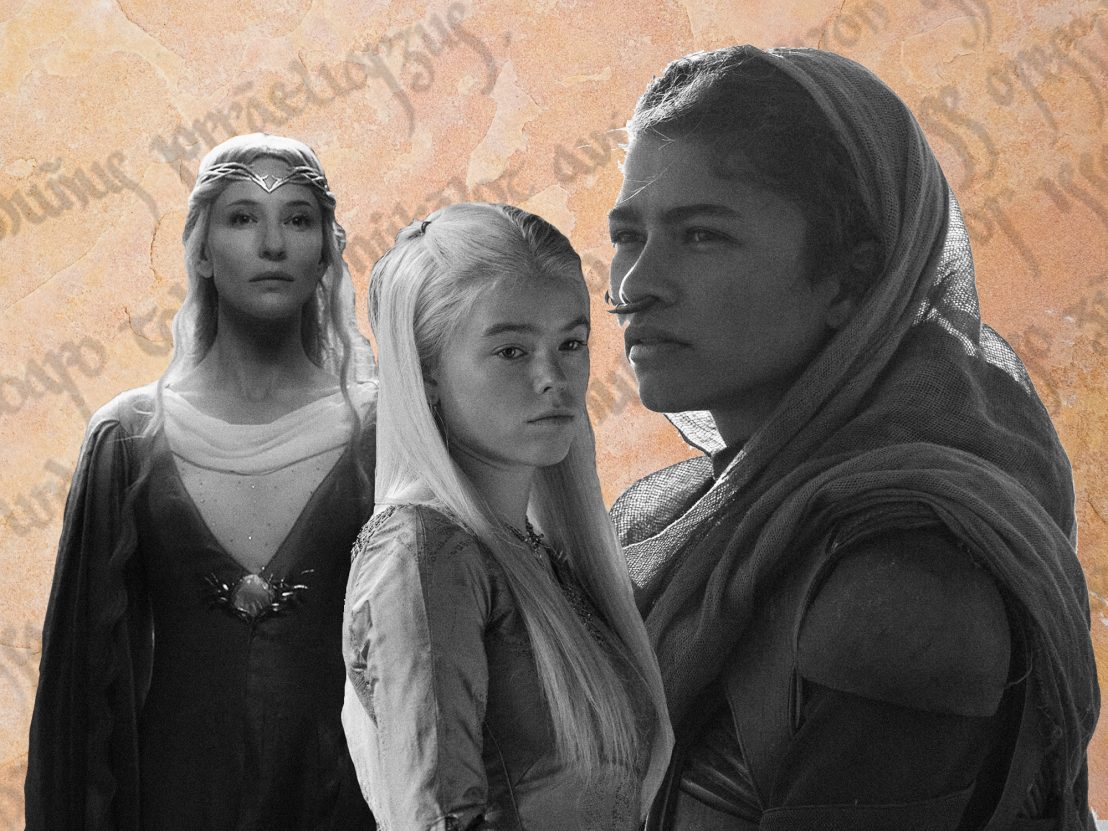

Jessie Sams and I recently went to the premiere of season two of Shadow and Bone, which we worked on together. We’re also working on season two of Halo, season two of House of the Dragon, the sequel to Dune, the next season of The Witcher and a brand-new film that I cannot tell you about yet, so you’ll have to wait until June to find out about that one!

Published 28 Mar 2023

Timothée Chalamet excels as space prince Paul Atreides in Denis Villeneuve’s spectacular widescreen epic.

Russian-language remake Khraniteli is right there on YouTube, for curious hobbits’ viewing.

Nicolas Philibert’s 1992 documentary is a sensitive and affecting portrayal of the deaf experience.