Movies have always reflected social attitudes and trends – and that could prove especially vital over the next four years.

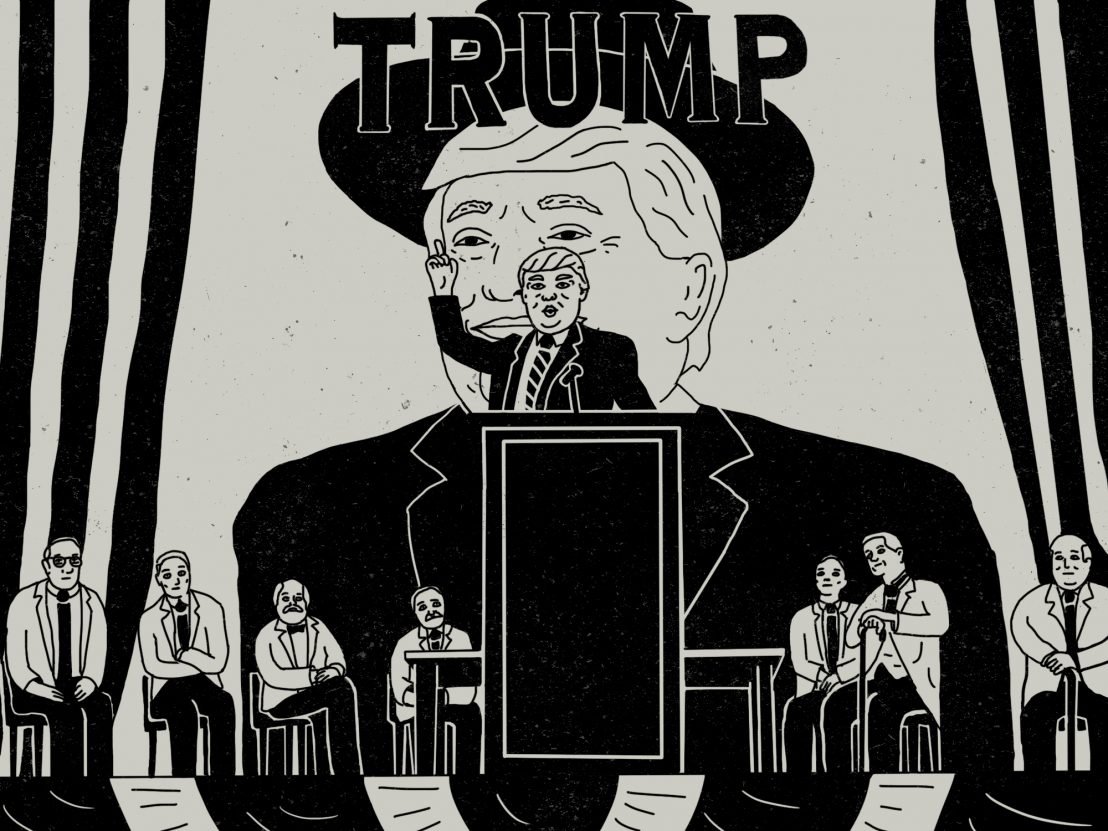

It’s fair to say that Donald Trump is a President unlike any other in the history of the American republic. He is the proverbial bull in a china shop, except that in this case, the china shop is the entire free world and the bull is a narcissist with the nuclear codes at his disposal. As the world comes to terms with Trump’s inauguration, there are plenty of potential consequences to ponder, many of them truly unprecedented.

Yet in one regard, President-elect Trump actually signals continuity with previous administrations: he won’t be the first commander-in-chief with connections to the entertainment industry. In fact, he won’t even be the one with the most extensive ties. That honour would have to go to Ronald Reagan, the Hollywood cowboy-turned-president. Fittingly, Reagan steered American foreign policy with the ‘good versus evil’ mentality of a gung-ho – if poorly written – movie character.

It’s been pretty typical of cultural commentators to expect that American movies will be flavoured by the attitudes and ideologies of the governing administration. The term ‘Reaganite Cinema’ was coined to describe a certain common thread in mainstream movies of the ’80s – namely a renewal of militarism, gun fetishism and a yen for physical strength and fitness. All of this was seen in response to or in light of Reagan’s own macho, traditionalist and aggressive political agenda.

With this in mind, it’s tempting to offer conjecture about what the next four years of a Trump presidency will yield. One can imagine Trump’s spirit in the vulgarity and xenophobia of Michael Bay’s Transformers series, where causal narrative logic is set aside for the sake of CGI smoke and mirrors. The New Yorker has reported that the mogul has an abiding love for Jean-Claude Van Damme action flicks, and often fast-forwards through the exposition to get the mayhem of the fight sequences.

It stands to reason that if the political powers-that-be are close to the financiers, producers and various executives who run Hollywood, the dynamic changes considerably. This may turn out to be the case with Trump, whose cabinet picks include several people who have worked directly inside the Hollywood system. Foremost of these is incoming Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin, a former Goldman Sachs banker and co-founder of Ratpac-Dune Entertainment. To those of us who’ve been looking, his name might be familiar – it appears in the credits of some massive recent blockbusters, including Avatar, Suicide Squad, American Sniper and Sully. The pulling power of several of these movies has been industry-shifting, suggesting that Mnuchin is in an distinguished position. Money talks.

Stephen K Bannon, the reviled Breitbart chief, is also a decades-long Hollywood player – even if his contributions to the filmmaking field have been largely to prop up various right-wing causes. His credits include fear-mongering documentaries like Occupy Unmasked. Perhaps even more germane to the topic of Trump’s insidious influence, there are a handful of business management firms and agencies with financial ties to Breitbart, including Freemark Financial Firm. The firm manages the business interests of many stars across television and film – including actors in Star Wars, Breaking Bad and the Fast & the Furious franchise. How – or indeed whether – these connections will influence mainstream cinema remains to be seen.

The major talking point after this year’s Golden Globes ceremony was a speech given by Meryl Streep, who was on stage to accept a Cecil B DeMille Lifetime Achievement award. It was an emotional plea for empathy and the defence of the free press, without once mentioning Donald Trump by name – and nonetheless leaving no doubts about to whom she was referring. It raised the ire of the PEOTUS himself, who responded – in trademark fashion – by tweeting that Streep is one of Hollywood’s most ‘over-rated’ actors.

With Trump’s reality TV background and the gilded tower he lives in, you’d be forgiven for assuming that he is media-friendly no matter the occasion. But his attitude of ‘all publicity is good publicity’ has markedly shifted since his political career took hold. Nowadays, you only have to look to Trump’s Twitter account to see exactly what he thinks about his detractors. He’s ready to publicly denounce and belittle anyone who dares to criticise him.

With clever insiders like Mnuchin and Bannon at his disposal – and a president that despises and targets even his mildest critics – who will want to stick their heads over the parapet? As much as Hollywood – exemplified by Streep – may appear activist-oriented at this time of crisis, translating an offscreen rallying cry into onscreen action is liable to prove difficult. Hollywood has a long history of, at least implicitly, upholding the status quo. If historical precedent is anything to go by, the century-old institutions of Hollywood are slow to progress, and very hesitant to alienate any of their audiences. For the most part, it’s anathema to mainstream Hollywood to put themselves at risk. From early ’40s anti-fascism to the protest years of the ’70s, political engagement always occurs a little bit late.

On a more optimistic note, Trump’s influence arrives at a time when the Golden Globes themselves are reflecting a beautifully disparate film landscape. The number of lead female parts and POC protagonists is steadily rising as evidence in Hidden Figures and Moonlight. Reformist tendencies are also popping up across film and television in the likes of 13th and Orange Is the New Black.

This progressive impetus was reflected in the inclusivity of Streep’s speech, as she celebrated the diversity and immigrant status that defines so much of the Hollywood community. It may be that the stereotypical cry of ‘liberal Hollywood’ is largely true, and that execs like Steve Mnuchin will be ostracised by the majority of the movie colony. Trying to predict the future, particularly these days, is a fool’s errand. For all we know, the major studios may soon start churning out anti-fascist agit-prop.

But it seems more likely that, as in the 1980s with Spike Lee, David Lynch and others, it will take independently-minded filmmakers to forge a path forward. In 2017, perhaps figures like Barry Jenkins and Ava DuVernay will continue to lead the way. That’s all we can reasonably ask of them. Of course, there isn’t necessarily any art-related silver lining to come. But now more than ever, subversive cinema – whatever that may ultimately look like – is more likely to come from outside the established perspective.

In order to meaningfully counteract the Trump administration, cinema must either provide inspiration or solace in one form or another. This doesn’t strictly mean explicitly political filmmaking – though that will undoubtedly play its part. More than anything else, what we really need is a variety of artists with the moral courage and fortitude to stick up for their principles.

Published 15 Jan 2017

Justine Smith examines how movies like The House of the Devil and Lords of Salem use nostalgia to expose a fractured national identity.

By Henry Bevan

Christopher Nolan’s film tells of a unqualified maniac who ruthlessly exploits a crumbling establishment.

In the first of a series of essays on Obama Era Cinema, Forrest Cardamenis counts the toll of US foreign policy during Barack Obama’s presidency.