Although the vast majority of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories are now in the public domain, a small handful written in the mid 1920s remain under copyright, creating legal dramas that continue to give filmmakers headaches.

In 2015, director Bill Condon was sued alongside distributors Miramax and Roadside Attractions for Mr Holmes, with the Doyle estate claiming that the film infringed on the few stories held under copyright. Five years after that case was settled, the estate filed a new case against Netflix for a near identical reason, stating that by portraying Sherlock as having emotions in their YA adaptation Enola Holmes, they infringed on the copyright of those same stories.

Given that Sherlock Holmes holds the Guinness World Record as the most depicted fictional character in film and television, cases like this are nothing new. But one largely forgotten Sherlock lawsuit from the early 1980s had far greater ramifications than anybody could have realised at the time, halting production on one series and freeing its director to create not only his first major film but also to co-found his own animation studio in the process.

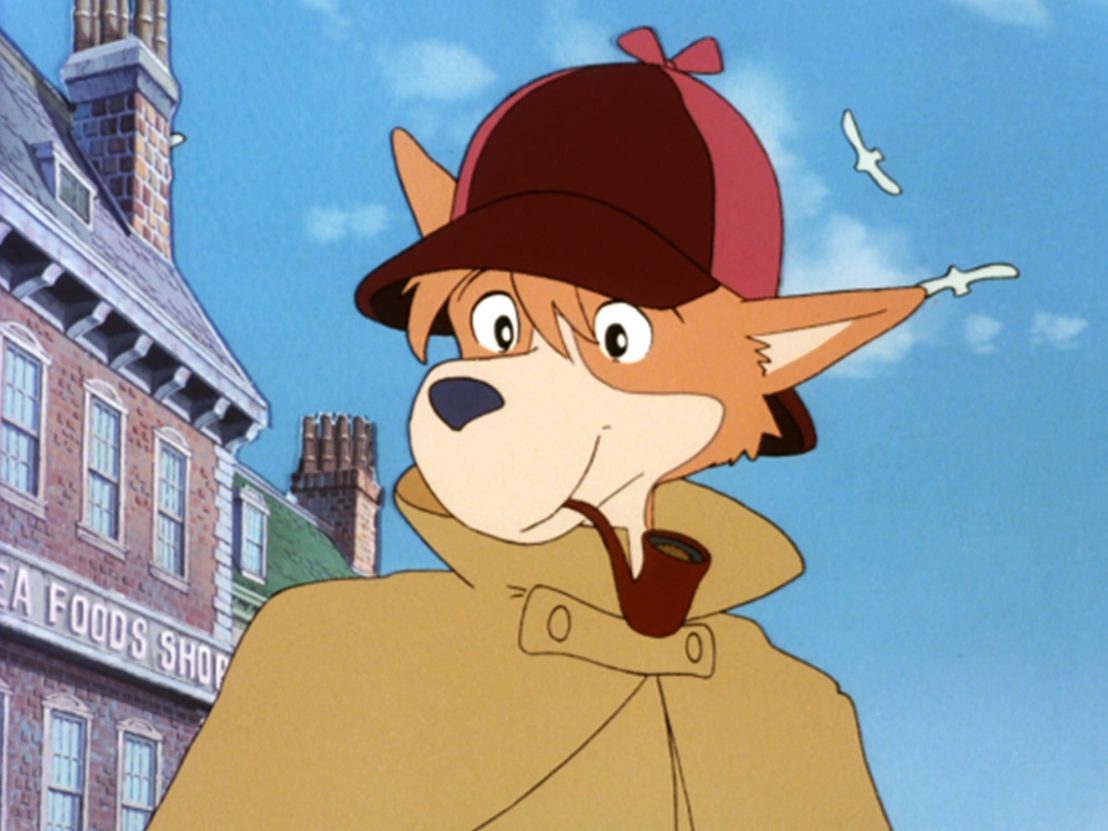

That director was Hayao Miyazaki, who, following the box office failure of The Castle of Cagliostro in 1979, moved back to the small screen to direct Sherlock Hound, a Steampunk reimagining of Doyle’s universe, with the famous characters all depicted as anthropomorphised dogs.

Midway through production, after completing six episodes bearing his directorial credit, the Doyle estate launched a copyright dispute that wouldn’t be resolved for a further three years. That same year, Miyazaki’s proposed second feature, a loose adaptation of Rowlf (adapted from the ‘Heavy Metal’ story of the same name by Richard Corben) fell through as studio Tokyo Movie Shinsha were unable to acquire the rights. Around the same time Miyazaki was approached by anime magazine Animage, who were impressed with his initial sketches for what would become Nausicaä, and asked him to start a new serialised manga for the publication.

In 1984, a little over two years after the first chapter was published, the film adaptation was released along with the first two episodes of Sherlock Hound, brought to cinemas to screen before the main feature. With the exception of Holmes and Watson, several character names had to be changed to soothe tensions with the Doyle estate (Moriarty became Moroach, for example), but the positive reaction led to the network resuming production. Kyosuke Mikuriya helmed the remaining 20 episodes, as Miyazaki was now fully devoted to his other projects, and all legal woes were resolved, allowing the original character names to be reinstated.

All of these factors have led to Sherlock Hound being reduced to a footnote in Miyazaki’s filmography, even though it stands as his final TV work after two decades working on the small screen. However, the episodes bearing his name offer a fascinating glimpse at many of the recurring visual and thematic obsessions we would go on to explore in his film work. Many of these are obvious stylistic quirks, such as the aforementioned Steampunk aesthetic, with Moriarty reimagined as a master inventor behind all manner of flying contraptions, informing the obsession with flying that would underpin the likes of Porco Rosso and The Wind Rises.

The show also recharacterises Mrs Hudson as a widow in her mid twenties. Although Miyazaki went on to make a film partially about a young woman finding liberation through old age, this youthful reinvention of Holmes and Watson’s landlady gives her the same agency as many of his other heroines. Here she becomes integral to several action sequences, showcasing her shooting and high-speed driving abilities; Miyazaki largely affords her agency without betraying her original characterisation. In one episode, ‘The Abduction of Mrs Hudson’, she even finds strength through performing domestic tasks, confusing Moriarty’s kidnapping plot by instating a sense of order into his deliberately disorganised living quarters.

The major difference between Sherlock Hound and Miyazaki’s later works is the insistence on making Moriarty a conventional villain, with a plot to get the better of the detective in nearly every episode. Still, even with this simplistic, broadly comedic characterisation there are still some similarities with the director’s typical ‘grey antagonists’; reimagining Moriarty as an inventor reinforces Miyazaki’s belief that villains often work harder than heroes, which is why he often ends up empathising more with characters he initially envisions as the antagonist.

Few people remember Sherlock Hound today and, due to rights issues, it remains largely inaccessible beyond a few episodes hidden away on YouTube. Viewed some 36 years on, it is clear that the show provided the foundation for much of Miyazaki’s work with Studio Ghibli, solidifying many of his recurring interests and signature aesthetic choices.

Published 23 Sep 2020

Isao Takahata’s unrealised passion project was intended as a follow-up to Grave of the Fireflies.

By Zoe Crombie

Tomomi Mochizuki’s teenage love triangle drama is fascinating outlier in the studio’s catalogue.

In the mid ’80s, the anime stable was struggling following back-to-back box office flops. All that changed with the arrival of a young witch.