On 17 April 1989, a year and a day after the release of his wartime masterpiece Grave of the Fireflies, Isao Takahata published an outline of his next project at Studio Ghibli. Whereas Fireflies depicted, in grim detail, how World War Two had ended for the Japanese, Border 1939 would show how it had begun: with Imperial Japan’s brutal invasion of continental Asia. By broaching a sensitive subject that animation had broadly avoided up to that point, the film would have broken new ground – had it been realised.

Takahata opens his outline with a synopsis. The setting is 1939, Japanese-occupied Seoul. Akio, a Japanese university student, learns that his friend Nobuhiko, who was said to have died in an accident while at a military academy in Manchuria, is still alive. Vowing to find him, Akio travels to Manchuria, which is also ruled by the Japanese. There, he discovers that Nobuhiko absconded to join the anti-Japanese resistance. To his great surprise, he learns that Nobuhiko, although raised by a Japanese family, is ethnically Mongol and identifies with the native peoples of the region.

Akio’s investigations are noticed by the Japanese police, who arrest and torture him. Resistance fighters free him and take him in, but they remain suspicious of him due to his Japanese blood. To prove his loyalty, Akio decides to help one of their members. The beautiful Akiko, another Mongol, is in peril, so Akio escorts her to her homeland. Cue a dramatic horseback flight across the Mongolian steppe. By day, the pair evade police and bandits by disguising themselves; by night, they sleep in yurts under starry skies. By the time they reach their destination, they have grown so close that it hurts to say goodbye.

With the sweep of a David Lean epic, Border 1939 immediately stands apart from Takahata’s other works, which rarely go big on action and plot. Akio’s courage and romantic streak mark him out as more classically heroic than the director’s usual protagonists. The canvas – Korea, China, Mongolia – is more vast than anything else the director attempted. But as his outline makes clear, he intended the film as more than just a slice of historical derring-do.

Takahata continues by describing three ambitions for the film. First: to reclaim the real world as an exciting setting for adventure stories in anime, as opposed to the imaginary realms of sci-fi. Second: to teach young Japanese viewers about their country’s inglorious history, lest militarism should ever appeal to them again. Third: to have them think about how they construct their sense of identity, both personal and national.

Presented in these terms, Border 1939 starts to look like vintage Takahata. Escapism, spectacle for its own sake, never really had a place in his work, and especially not by this point in his career. On the contrary, his greatest films strive to redirect our attention back to ourselves. In their messiness and nuance, the situations and relationships he depicts mirror those in our lives, our society. The mistakes and injustices committed by his characters are significant, because they point to what we can improve in our world.

Border 1939 took aim at one of the greatest injustices in Japan’s history. Its experiment with empire had left a legacy of bitter resentment across Asia (while also leading the country into a catastrophic war with the Allies). And yet, by the 1980s, Japanese society remained very conflicted in its ways of interpreting this dark chapter in its past. Many openly condemned their country’s crimes, but many more did not, and Takahata worried that the younger generations were growing up ignorant of their history.

Hence the need for this film. Its story was based on the novel ‘The Border’ by Shin Shikata, who had himself lived as a Japanese boy in occupied Korea. Shikata spent years in blissful ignorance of the colonial regime’s brutality, but as a teenager he became sensitised to it – and to the fierce resistance movements it stirred up. His realisation plunged him into painful self-reflection. What does it mean to feel allegiance to a nation? And what happens when that nation does wrong?

These are the questions Takahata wanted to ask. “People start developing a sense of self once they come into contact with others,” he writes. “If your country is invaded by another, which then tries to repress your culture, your sense of nationhood becomes stronger. But what if we take the invader’s perspective? I wonder whether, by tackling the complex identity issues on the continent and Korean peninsula at the time, we can get viewers to start thinking about the internationalist spirit that is now needed among the Japanese.”

Takahata had already attempted a critique of Japanese nationalism in Fireflies. Although the film is set during the American firebombing of Japan at the war’s end, it also alludes to the ugly jingoism that set Japan on the warpath in the first place. But it does this subtly – maybe too subtly – and most viewers remember only the characters’ suffering, leading some to accuse Takahata of commemorating Japanese victimhood while skating over Japanese atrocities. Perhaps he conceived Border 1939 as a response to this criticism.

We’ll probably never know. In June 1989, the Chinese government viciously suppressed political protests on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. Public opinion in Japan, as elsewhere, turned against China, and Ghibli’s distributor deemed that a film partly set there was too risky. Border 1939 was axed before entering production. Aside from Takahata’s outline (reprinted in his book ‘Eiga o tsukurinagara kangaeta koto’ [Thoughts while Making Movies]), no materials from the project have been released. I’ve seen no development artwork. Ghibli declined to comment for this article.

In the end, a film about Asian anger over Japanese violence was derailed by Japanese anger over Chinese violence. The irony won’t have been lost on Takahata, who continued to campaign for international peace and cooperation until his death in 2018. In these decades, his activism provided an outlet for this message. After the collapse of Border 1939, he went on to make four more exquisite features at Ghibli, starting with 1991’s Only Yesterday. But never again did his films confront the fraught matters of geopolitics.

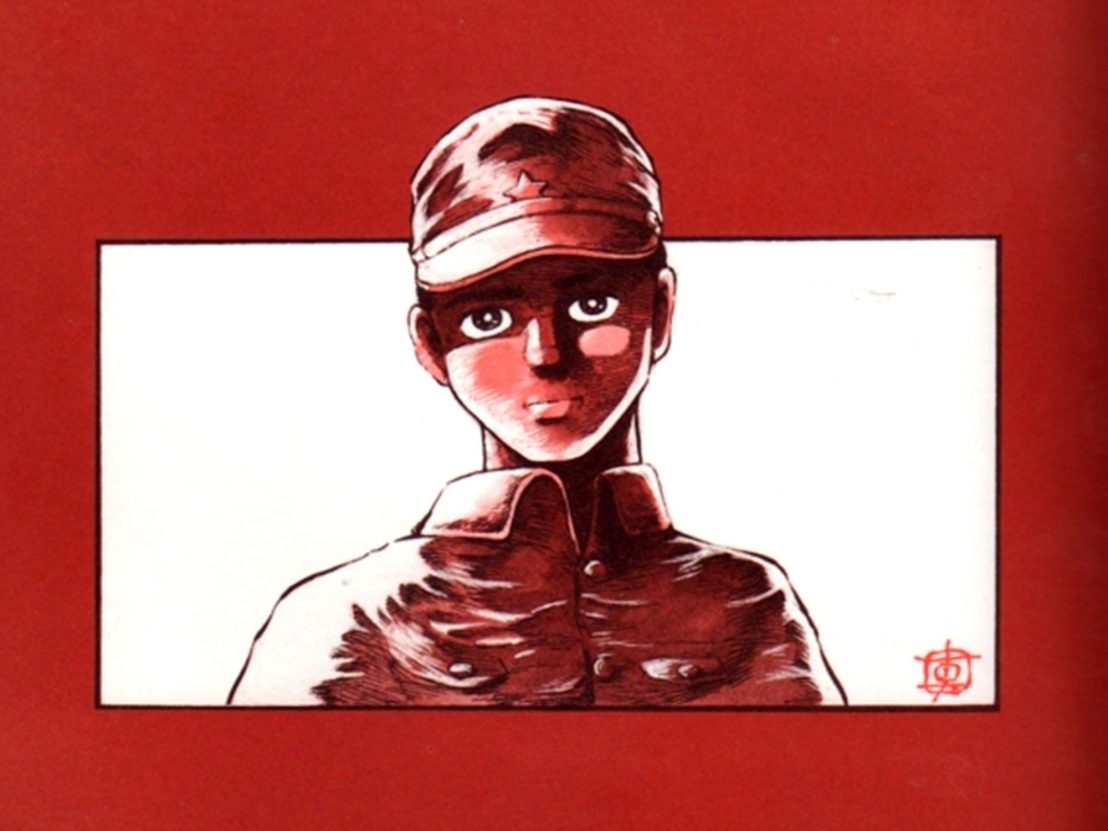

NB: The above image is a detail from the cover of the second volume of Shin Shikata’s ‘The Border’. It was not produced by Studio Ghibli.

Published 7 Jun 2020

With the release of Studio Ghibli’s back catalogue on Netflix, we look back at one of their unsung greats.

In the mid ’80s, the anime stable was struggling following back-to-back box office flops. All that changed with the arrival of a young witch.

By Zoe Crombie

Tomomi Mochizuki’s teenage love triangle drama is fascinating outlier in the studio’s catalogue.