Dirk Bogarde’s career was a contradiction. In the 1950s he regularly topped the movie charts as one of Britain’s most popular stars, but privately he admitted that beneath the glamour of it all he was deeply unsatisfied. At first, he wore his stardom with a cool nonchalance, as best summed up in one of his autobiographies ‘Snakes and Ladders’: “[John Davis] would make me into one of the biggest Stars, or biggest Box Office Attractions, Rank had ever had. How did I feel about that? I felt fine.”

Born in West Hampstead on 28 March, 1921, to former actress Margaret Niven and Ulric van den Bogaerde, Art Editor of The Times, Bogarde’s acting career seemed almost pre-destined. But, in stark contrast to his eventual movie stardom, he first served as a lieutenant in World War Two – the brutality of which changed him irrevocably.

After making around 30 commercial pictures with The Rank Organisation, Bogarde found greater freedom by selecting more personal fulfilling projects. In 1961 he played a gay lawyer in Basil Dearden’s Victim, expressing how at last he felt he was in a film which both “educated and illuminated”, and followed this by reuniting with director Joseph Losey, with whom he had made The Sleeping Tiger almost a decade earlier.

At that time, Losey had mentioned his interest in turning Robin Maugham’s novel ‘The Servant’ into a film with Bogarde as Tony, the affluent young Londoner seeking a manservant. But by now the actor was, in Losey’s words, “too old to play the boy.” Or, as Dirk later put it: “[I] had to play the servant because there was no money for a star like Ralph Richardson.”

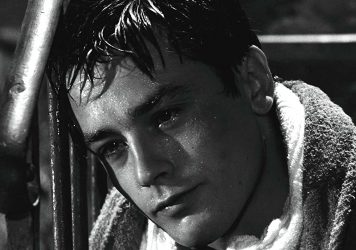

Bogarde’s performance as the sly Hugo Barrett is one of his greatest, and it earned him his first BAFTA win. He dominates the screen with searing charisma in a film that explores, to a disturbing degree, the servant-master relationship. Gone is the perfectly coiffed hair and shoulder padding of his earlier comedy crime noir roles. Instead, Bogarde looks suitably unglamorous with slicked greasy hair and heavy bags under his eyes.

The brilliance of Bogarde’s performance is that we never quite know what Barrett is thinking. We have only glimpses which are emphasised by Douglas Slocombe’s masterful camerawork. The opening tracking shot surveys the bare wintry trees and rooftops of Chelsea before focusing on Bogarde. From there the camera starts to pan as he keeps walking, remaining in sight but getting further and further away. With a suitably palpable air of mystery, Barrett is just out of reach. However, what we do see is a glimmer of his unflappable composure as he crosses the busy street, casually swinging a brolly back and forth while making no attempt to hurry.

His umbrella makes notable appearances throughout the film, not least in the scene where Tony (James Fox) is interviewing Barrett for the eponymous position. As Tony quizzes him on his cooking prowess, Barrett leans the umbrella handle precariously between his legs, barely masking it with a bowler hat. His eyebrows dance suggestively as he boasts of his soufflé making ability. Of course, the key to a good soufflé is a perfect rise. There’s a delight in his sly innuendos which only add to the film’s tension.

Whereas Victim was more explicit, the first English-language film to say the word ‘homosexual’, The Servant only alludes to it. One reason being that Bogarde’s agent who he was secretly in a relationship with, Anthony Forward, was concerned by the possibility of him acquiring a “homosexual image.” Gay rendezvous between men were not yet decriminalised, and in The Servant Bogarde expertly demonstrates a more embedded approach.

Bogarde’s main weapon were his eyes: boyishly wide yet just as intense and purposeful, as though they’re undressing you and mocking you simultaneously. Barrett seems aware of the penetrating power they possess, and like a sinister foxtrot – quick, slow, quick – he occasionally slows right down in between whisking around the house, zoning in on his subject with that steely gaze. “I’m afraid it’s not very encouraging, miss,” Barrett starts as he sees Tony’s girlfriend Susan (Wendy Craig) out. He lingers on her, a little too close for comfort, before continuing: “…the weather forecast.” She leaves bemused, later telling Tony that she doesn’t feel totally at ease around Barrett.

As the film goes on, Barrett’s erratic behaviour escalates from overstepping his bounds to betraying the couple completely: “I’m nobody’s servant, I run the whole bloody place!” he roars in stark contrast to his softly spoken ‘yes sirs’ at the start of the film. In the final scene he pushes Tony about like a rag doll, treating his zombified, intoxicated state as just another sinister game – not unlike the menacing version of hide-and-seek they play earlier. Barrett goes from physically dominating the space to emotionally dominating his master, and Bogarde’s electrifying turn makes the entire descent into chaos seem entirely plausible.

Published 28 Mar 2021

The French screen idol is at his most open and vulnerable in Luchino Visconti’s 1960 crime drama.

A welcome re-release of Basil Dearden’s chilling survey of life as a gay man in London of the early ’60s.

A new documentary reveals how Björn Andrésen was plagued by the title director Luchino Visconti bestowed on him.