Mike Leigh’s 1993 black comedy Naked remains one of the British filmmaker’s most popular and enduring works, capturing in its two-hour midnight odyssey through the grimy urban sprawl of London a raw and vital voice. The film’s real success, though, is largely predicated on the central performance of David Thewlis, whose turn as the paranoid, depraved, nocturnal deviant Johnny is one of the finest of the decade.

Leigh’s screenplay is a rapid-fire, profane miscellany of biblical allusion, old wives tales, and British slang that Thewlis spits and gutters through like a man possessed. Johnny’s diatribes against the ‘doomed’ global population often border on the manic, and his nihilistic worldview becomes the axis around which Leigh’s bleak and brutal ode to the British working-class spins indefinitely.

“I can’t believe you’re here?”

“I’m not here.”

Interactions like this, between Johnny and his old girlfriend, Louise, define Leigh’s protagonist as a contradiction, a strange and sinister figure who resents life and yet tolerates it through a diet of cigarettes and cheap booze. Yet for someone who puts so little stock in the value of life, Johnny is endlessly curious and inquisitorial. The majority of his lines in Leigh’s screenplay are questions – either to himself, to the apathetic city through which he wanders, or to the various strangers he meets along the way. Yet he seems ambivalent to finding any answers and instead derives a morbid pleasure from probing the flesh and marrow of human existence with his barbed, mordant wit.

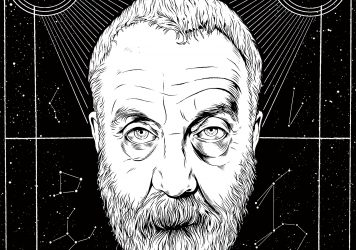

But it’s not just Thewlis’ mastery of Leigh’s script that marks his performance as revelatory. The physicality he brings to Johnny, from his arrogant and cartoonish gait to the way he often looks up, child-like, at others through his greasy fringe, is responsible for his lasting impression long after the credits roll. He casts a gaunt and haggard figure, an urban ghoul who haunts department store foyers or the fluorescent stairwells of tube stations after dark. His coarse, patchy facial hair and his dirty, soot-black ulster jacket mark the unmistakable look of the vagrant, but his gallows humour and erudite knowledge mark him out from the rest of the city’s destitute. He is, in a word, a nobody. As anonymous as a wisp of smoke over Battersea.

It’s the chameleon-like adaptability of Thewlis, though, that gives Johnny his animated brilliance. Undaunted by anyone or anything, he talks to night porters, drug addicts, and waitresses indiscriminately, sharing with them all his aphoristic outlook on a life he considers futile and, frankly, a waste of everyone’s time. Johnny has survived up to the point where we meet him, sexually assaulting a woman in a dark Manchester alleyway, because he finds a sick pleasure in elongating his own tormented existence. Thewlis’ moody and bitter portrayal of Johnny marks a character to whom life constitutes putting one arbitrary foot in front of the other, and seeing where you end up.

Above all else, though, what is most striking about Thewlis’ all-consuming performance is the paradox of empathy versus disgust we are left wrangling with at the film’s close. Here is a man who has raped women, who steals, who lies, who would kill his own kin to save himself. We watch him manipulate and assault his way into trouble, and then talk himself right back out of it. We should feel nothing but disgust for Johnny, nothing but contempt. And we do. But there is another feeling stirred up by Thewlis’ raw performance.

For all of Johnny’s faults, he is uncompromisingly human. And humans feel empathy for others, sometimes against our better judgement. As Johnny limps off through the harsh dawn of a London council estate in the film’s final moments, stolen money in his coat pocket, we are left wondering if such a man could ever be worthy of our sympathy. Could he ever be redeemed? It is testament to Thewlis that such questions are raised at all when Johnny could seem so black-and-white in the hands of a lesser actor.

It’s not just Johnny with whom we are left feeling deeply conflicted at the end of the film, but ourselves too. “We’re not fuckin’ important. We’re just a crap idea,” Johnny says to a security guard midway through the film. After bearing witness to Johnny’s foul excursion into London’s underbelly, it’s hard to argue with him.

Published 1 Jul 2018

LWLies sits for the British cinema icon who doesn’t mince his words to talk Mr Turner.

Timothy Spall grunts his way to glory in Mike Leigh’s elegantly composed portrait of JMW Turner.