It’s been over 10 years since I experienced being locked in a classroom as a shooting unfolded two floors below. The images of that day come in flashes: DW Griffith’s Broken Blossoms, the gunshots, people screaming in the hallway and a table was pushed against the door. The SWAT team eventually came to clear the school, they pointed guns at us. We were evacuated and a classmate turned to me once we reached safety, and asked, breathless, “Did you see all the blood?” I did not, but then again, I don’t remember the experience of that day. It was more like I was watching it from the outside and everything I saw or heard was filtered through another screen or someone else’s point of view.

Years later, reading Dave Cullen’s book ‘Columbine’, I was struck by the way he describes the immediate aftermath of the shooting, when parents and children were reunited. He observes that the parents were crying but, for the most part, the kids were not. He wrote about the students, “A vast number said they felt they were watching a movie.” That’s how I felt too.

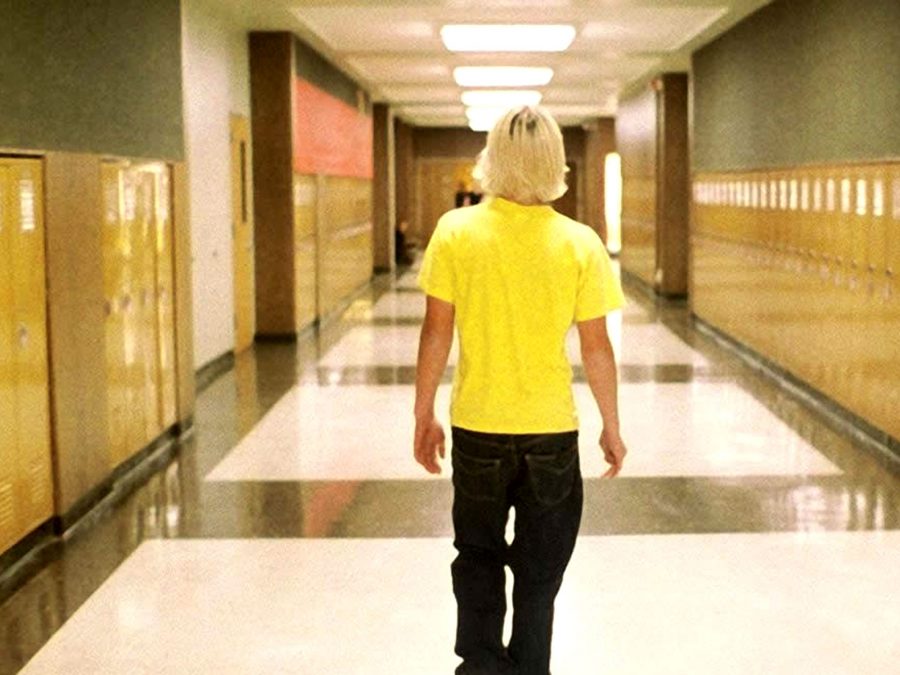

Elephant became a very important film for me. In film school, screenings were preceded by warnings and discussions as to how it might relate to our experiences. We discussed the film in the context of independent American cinema but also the theories of Robert Bresson and his use of non-actors. Van Sant’s particular use of a third person shot, where the camera is positioned behind a character’s head was common in video games but also served to create a point of view that was vacant and non-human, an empty witness to trauma.

Bresson was also fond of these kinds of shots, using point of view to create meaning in the viewer, while his mannequins remained vacant and empty. For me, the final massacre in Elephant also seems connected to the little girl in Mouchette, who in the film’s final scene, keeps rolling down towards the river until she falls in: They are different stories of self-annihilation in reaction to a cruel and violent world.

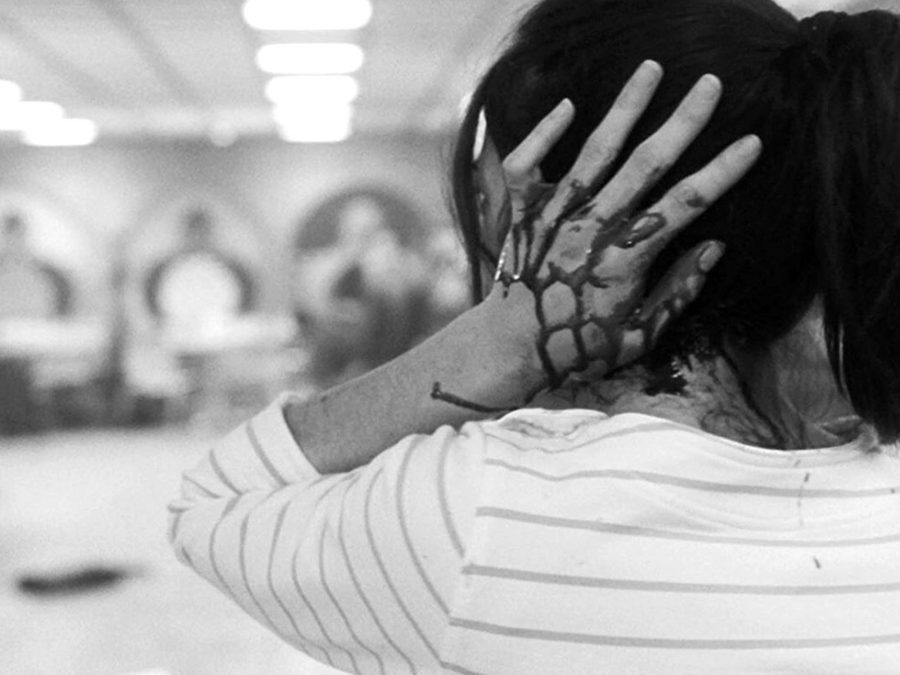

Just a couple of years after my experiences, Denis Villeneuve released Polytechnique in Quebec. The film represented a well-known massacre in the province that happened in 1989 when Marc Lépine entered the École Polytechnique and killed fourteen women. He wrote an extensive manifesto against feminists at the time, believing that his spot in the school had been given away to women. The script fictionalised the experiences of the young women and many aspects of the event, but in terms of actions and movements, remains very close to what happened on that day in December. The script relied very closely on the public coroner’s report which reconstructed Lépine’s trajectory through the school.

Shot in black-and-white, the film opens with a shocking incident by the photocopy machines, as two young women are shot. One, hit in the ear, loses a grip on her surroundings. We briefly experience the limits of her point of view, in particular, the ringing in her ears that dulls the sounds of screaming, shots and running. Controversially, Villeneuve’s is intimate and visceral, bringing to the screen the emotional experience of living through a shooting.

Everything about Villeneuve’s film felt uncomfortably familiar. This was not the distant world of America, it was Quebec, my home. Strangely, above all else, it was the Brutalist architecture of the school that spoke to me the most. The heavy concrete designs proliferate through Montreal, especially in public buildings and schools. Seen as a reaction to the open, optimistic style of architecture common during the 1930s and ’40s, Brutalist designs were fortress-like and functional.

In my experience as well, they tend to be structured like labyrinths and characterised by dark corners and long hallways. I’ve always felt it was a style of architecture reflective of Montreal’s apocalyptic energy, a city that seems built for a post-human world. Villeneuve focuses in on details within these spaces like the crudely carved lines in concrete, the thunderous buzz of phosphorous lights and a rattling radiator.

While most of the film is focused on the victims, the nameless shooter in the film has a voiceover and as we are given purview into his alienation and rage. He reads his manifesto, as he plans to take violent action against the faceless feminists he believes wronged him. His reasons are articulated, but rendered madly, as the rest of the script makes it clear how wrong-headed his assumptions are. His actions are unforgivable, born out of resentment and fear. As in the case of many events of this kind, it’s easy to describe what he does as senseless but is that really accurate? As a non-American, it was always easy to look at the mass shootings taking place across the border as a reflection of their problem, a rage that had not infected my environment, but it seems insincere to pretend these acts of violence spring out of nothing. In the film, he sits outside of his car writing one last note, saying, “Mother, I’m sorry but it was inevitable.”

There’s a scene in which one of the students is waiting to do some photocopies when his eye catches Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, printed on newspaper and put up on the wall. A slow-zoom draws us into black and white shapes of cubist suffering, as animals and man are ripped apart by an unseen explosion, a reference to the bombing of Guernica in Spain that happened in late April, 1937. More profoundly, this link to the past seems to bring in the events of Polytechnique into a large discussion of violence and suffering. Are the shooters really alienated from our society, or are they a mirror image of its darkest impulses?

Ten years later, I no longer have nightmares about what happened to me. Rewatching films that once sucker punched me, I still have an inclination to weep, but it’s cathartic rather than haunting.

Now I think of Polytechnique in conversation with another act of mass violence in Quebec. In 2017, Alexandre Bissonnette went into a mosque in Quebec City and killed six people. He has said he was motivated by the Canadian government’s lax immigration status, referencing tweets made by Donald Trump when he tried to enact his Muslim ban in January, 2017. With Bissonette, it’s hard not to see him as a reflection of the worst instincts of my culture.

There is a cruel irony that as Bissonette’s sentencing is underway, the biggest story in the province is a backlash against a young Muslim woman who wears a hijab and wants to become a police officer. The parallels between Bissonette’s word and actions as they connect to a wider cultural voice of conspiratorial paranoia are rarely drawn. Bissonette is not an anomaly, he’s merely putting into action some of the worst impulses present in a vocal majority within the province. Rather than be alienated from the culture, he is forged in it, which I’d venture to say is more common than not when it comes to these acts of public violence.

It’s easy to treat the shooters as alienated, a lone wolf perpetrating random acts of violence against the culture that created them. Yet it seems increasingly obvious that the society itself may be poisoned, that these acts of violence are products of our culture rather than in conflict with it. In my own search for peace and healing, I recognise that the burden extends to the society as well. These incidents which become more frequent and more deadly cannot be willed away and it seems hopeless to accept them as the new normal. Part of the process for change will be an acceptance that there is a social problem at work, that the violence does not spring out of an abyss, but perhaps is a natural reaction to a culture already forged on hatred and violence.

Published 20 Apr 2018

By Brian Brems

What does it mean to be an American who loves Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver but hates gun violence?

The film’s glamorisation of vigilante justice resonated with an increasingly paranoid audience in 1974.

This hard-hitting doc-fiction hybrid explores the growing epidemic of American gun crime.