When I was an undergraduate at Southern Illinois University, I sat on the planning committee for The Big Muddy Film Festival, which hosted screenings of films submitted from all over the world, in addition to presentations of well-known documentary and narrative features. It was tradition to host midnight screenings at the local University 8 cinema as a way of getting students interested in the festival’s larger film programme. One year, I lobbied for Taxi Driver, and when we couldn’t get the rights to show Brazil, I won. We’d be showing one of my favourite films on the big screen, on 35mm. I’d never seen it that way before. I was elated.

We screened the film on 26 February, 2005. Turnout was good. These were the days before digital projection, when most cinemas still ran everything in 35mm, but I remember being astounded by the crispness of the images. The deepness of the colours, the clarity of the focus – they stood in stark contrast to how I was accustomed to watching it, on my tiny TV/VCR combo in my room, on a special edition VHS. The print was miles away from the scratchy tape I’d rented from Blockbuster back in 1999, the first time I saw the film.

That same night in Chicago, just around the time our screening of Taxi Driver was emptying out, a young man and woman were left wounded by a shooter near the United Center (where the Chicago Bulls play).

This is life in America.

Four years later, as a graduate student at Northern Illinois University, I served as Vice President of the NIU Film Society. We screened Taxi Driver on 12 November, 2009. It was the best-attended screening we put on in four semesters of my tenure there; just one week after a gunman at Fort Hood, Texas killed 13 people, and 21 months after a mass shooting on the NIU campus left five students dead. I had watched that chaotic scene unfold from the window of a classroom just upstairs from the one where we screened Taxi Driver to a room full of students.

I showed Taxi Driver to a handful of students in the first film class I ever taught at a community college on 2 November, 2012. It was here one month later that I found out about the elementary school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut. I showed it again at another community college (where I am currently an Assistant Professor) on 22 July, 2014, as a part of a series on Martin Scorsese. That day, CNN ran a story about the 47 people who had been shot in Chicago the previous weekend. And then again on 25 February, 2016, the day that former Arizona representative Gabrielle Giffords, a survivor of a mass shooting, announced a collaboration with Minnesota activists for new gun regulations. On 16 October, 2016, I went with a group of friends to a 40th anniversary screening of the film at our local Cineplex. That night, two people died in an apparent murder-suicide in Florida.

It wasn’t difficult to match these screenings of Taxi Driver to contemporaneous examples of the three interlinked gun problems plaguing the United States: everyday, but often unremarked upon gun violence; an epidemic of gun suicides; and finally, mass shootings.

This is not to suggest that Taxi Driver – or any form of violent media, for that matter; too often easy scapegoats in this conversation – are responsible for this mayhem. I am living proof of the ability to hold two concurrent, conflicting thoughts. I believe that gun violence is a devastating scourge that must be combated by any and all means necessary. I also believe that Taxi Driver, a film built on a scaffold of gun violence and firearm fetishisation, is an essential piece of cinema from which I derive great personal and artistic meaning.

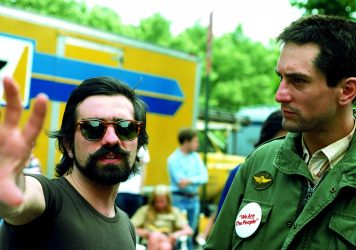

When it was released in 1976, Taxi Driver was regarded as extreme in its depiction of violence. As Martin Scorsese explains on a director’s commentary for the film, the climactic shootout sequence went through a complicated colour desaturation process in an effort to please the ratings board, giving the bloodbath an orange hue. Its origins were dark and violent, as well. Paul Schrader, the film’s screenwriter, has said, “At the time I wrote it I was very enamoured of guns, I was very suicidal, I was drinking heavily, I was obsessed with pornography in the way a lonely person is, and all those elements are upfront in the script.”

The film’s central character, the lonely New York City cabbie Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), is a smoking, hissing fuse. His isolation, his racism, the sense of betrayal and rejection he feels by Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), his feminine ideal – these are the toxic ingredients that make up the profile of so many of America’s troubled young men, each of whom, like Travis, picked up a gun and pulled the trigger in a desperate effort to be heard.

When I view Taxi Driver today, I think about the clash between its superior, even beautiful technical craft and the horror of its disturbing content. The early sequences of Travis behind the wheel of the cab, looking out the windshield at the naked city around him, are masterfully edited. Scorsese manages to create a fluid, lyrical montage of the quotidian as Travis settles into his new job. A series of green lights fly by. The cab’s meter goes up, then down. Bernard Herrmann’s jazzy score floats between pleasant and ominous. First, there is Travis’ excitement, which turns to boredom and, eventually, simmering rage.

Watching Taxi Driver is like sticking one’s fingers close to – but not actually in – a burning flame. Harvey Keitel’s Charlie in Scorsese’s Mean Streets holds his fingers in the fire as penance, to remind himself of the pain of hell that awaits him should he sin. But Travis holds his clenched fist over the burning stovetop as a way of toughening his body and mind. Shortly after this moment, Travis buys his first guns from Easy Andy (Stephen Prince), a travelling salesman. The camera adopts Travis’ fascinated gaze as it tracks across the guns, laid out on the bed in a line. In these weapons of death, Travis sees an identity, a purpose, and a way to reach out to those who have ignored him.

As an adult, I struggle to comprehend what he is feeling in this moment. I do not have access to the emotion which overcomes Travis. I cannot look at a gun and see any part of myself holding it, taking aim, and firing. But I do remember a time in my adolescence where I would twirl a plastic, trigger-clicking pistol that I had spray-painted black, while watching television. I can still hear the thrill of the high-pitched crack of a cap gun. I don’t have to think too hard to imagine myself carrying a wooden rifle, hustling through a forest with childhood friends. This is a typical American boyhood, I think. When I was small, the idea of a gun made me feel big. When I got older, I found other ways to chase the same feeling.

In America, though, there are those who never find a substitute. Mass shooters turn to guns to express what their voices cannot articulate: masculinity, racism, sexuality. Ten years before Travis Bickle, there was Charles Whitman. According to Rick Perlstein’s ‘Nixonland’, Whitman, “a 25-year-old former marine sharpshooter climbed to the top of the University of Texas’ ceremonial tower and started blowing away passersby at random… Initial reports were that Charles Whitman was just another ‘all-American boy’.” There had been mass shootings in the United States before, but this one became yet another ghastly current in a swirling maelstrom of horror that enveloped America in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Taxi Driver was not the first film of its era to portray a gun-toting killer with such frankness. In his book ‘Easy Riders, Raging Bulls’ Peter Biskind notes that Peter Bogdanovich’s 1968 film Targets was, “loosely based on the recent rash of mass murders,” including Whitman’s rampage. The film was not a box office success, which Bogdanovich argued was in part because of “Martin Luther King’s assassination, which made people leery of sniper films.” Gun violence would follow Scorsese’s film when, in 1981, “John Hinckley Jr, imitating Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle, attempted to assassinate President Reagan in the hope of impressing Jodie Foster.” The film’s power is undeniable.

I feel connected to Taxi Driver perhaps more than any other film. And yet, given my own personal feelings towards guns and the violence they enable, I should be repelled by it, just as I should be disgusted by its character’s racism, sickened by his misogyny. The scene of Travis meticulously crafting his ace-in-the-hole, the sleeve-deploying pistol, should madden me, but it amuses me. The way Scorsese carefully frames the process of sawing the drawer track in two, or the way he heightens the sound effect of the pistol snapping into place, announce themselves so dramatically, with such cinematic conviction, that I cannot help but take gratification from these images. At the same time, I know that preparations just like these may, at this very moment, be ongoing in a dimly lit, quiet basement somewhere in the country. And their consequences will be heartbreakingly, violently real.

I do not see myself, as I am now, in Travis Bickle. However, if I squint, I can see in him what I might have been. There is the potential for darkness within us all. I fit the basic profile – white, straight, male. Somehow, the switch in me never flipped, never could flip, never will flip. I watched violent movies. I played with toy guns. I still, to this day, own a Travis Bickle Halloween costume, complete with a ‘We Are The People’ button.

Much of Taxi Driver is about looking. Travis looks at Betsy from the cab. Travis looks at the screen in the darkened porno theatre. Travis looks at his fellow cabbies.

Travis looks in the mirror.

This is idea from Schrader’s screenplay that became the film’s most famous, iconic scene. De Niro improvised the “You talkin’ to me?” line while pulling his enormous .44 Magnum on his own reflection. The scene’s lasting impact lies in its relative sweetness. In this moment, Travis appears as a little boy, horsing around in his room with his toys. The scene’s inherent humour, which renders Travis almost harmless in his innocence, is brilliantly disarming. This same boy will seem very much a man later in the film, first in his attempted assassination of the candidate Charles Palantine (Leonard Harris) and then in his brutal slaughter of Sport (Keitel) and the other pimps.

In America, we ignore the boys in the mirror at our peril. In this way, Taxi Driver remains a valuable and vital work of cinematic art. For all of its ugliness, it forces us to confront those demons that lurk within our society, within our politics, even within ourselves. I will teach the film again. I will see it again on the big screen. I will continue to look in this particular mirror, in the hope that one day, I see a different America reflected back at me.

Published 4 Mar 2018

By Paul Risker

With Martin Scorsese’s seminal crime drama finally out on Blu-ray, we gauge the film’s enduring influence.

By Matt Thrift

The veteran Hollywood maverick talks Dog Eat Dog, Scorsese and the challenges of modern moviemaking.

A comprehensive guide to the directing credits of this great American auteur, from Mean Streets to The King of Comedy to Killers of the Flower Moon.