Following on from their recent Japanese film season the BFI are finally joining us in the muck and programming an Anime season. Lead by programmer Justin Johnson, this first part of the season in April (with more to follow in May) covers a fairly broad scope, from the industry’s foundational works to modern classics to more recent hits. Outside of the following highlights there’s more to discover: such as Eiichi Yamamoto’s vivid watercolour nightmare Belladonna of Sadness (introduced by Helen McCarthy – a crucial voice in anime academia), plus Yamamoto’s 60s series Kimba the White Lion. Then there’s the opportunity to overwhelm your brain with anime on the biggest screen in the UK – with Ghost in the Shell as well as Mamoru Hosoda’s Belle playing in the IMAX. Here’s some of the highlights from their programme, which kicks off on 28 March.

Inu-Oh

The latest film from Masaaki Yuasa – director of Devilman Crybaby, Night is Short, Walk on Girl and Elvis Costello’s favourite TV show of 2021, Keep Your Hands of Eizouken – Inu-Oh is another idiosyncratic feather in the animator’s cap, though it’s also his final one with Science Saru (for now). Based on the novel Tales of the Heike: INU-OH by Hideo Furukawa, a sort of fictionalized spin-off from The Tale of the Heike, Yuasa transforms this historical fiction into an anachronistic rock opera. Inu-Oh follows Tomona, a blind musician specialising in the biwa. He eventually meets and befriends the eponymous Inu-Oh, a noh theatre performer shunned for their atypical appearance – one that also lends him a special talent as a dancer. They strike up a creative partnership that sparks a wild change in the landscape, one that attracts oppressive response from local leaders.

Even for Yuasa the film shows astonishing visual flexibility, mixing realism and abstraction, traditional and modern art, the macabre and the comical; it’s anarchic in the same way its musical deuteragonists are. Like Ride Your Wave before it the film has a surprisingly tragic edge to it too, mournful for the fates of its characters and perhaps in a metatextual sense, the end of Yuasa’s journey with the studio he founded.

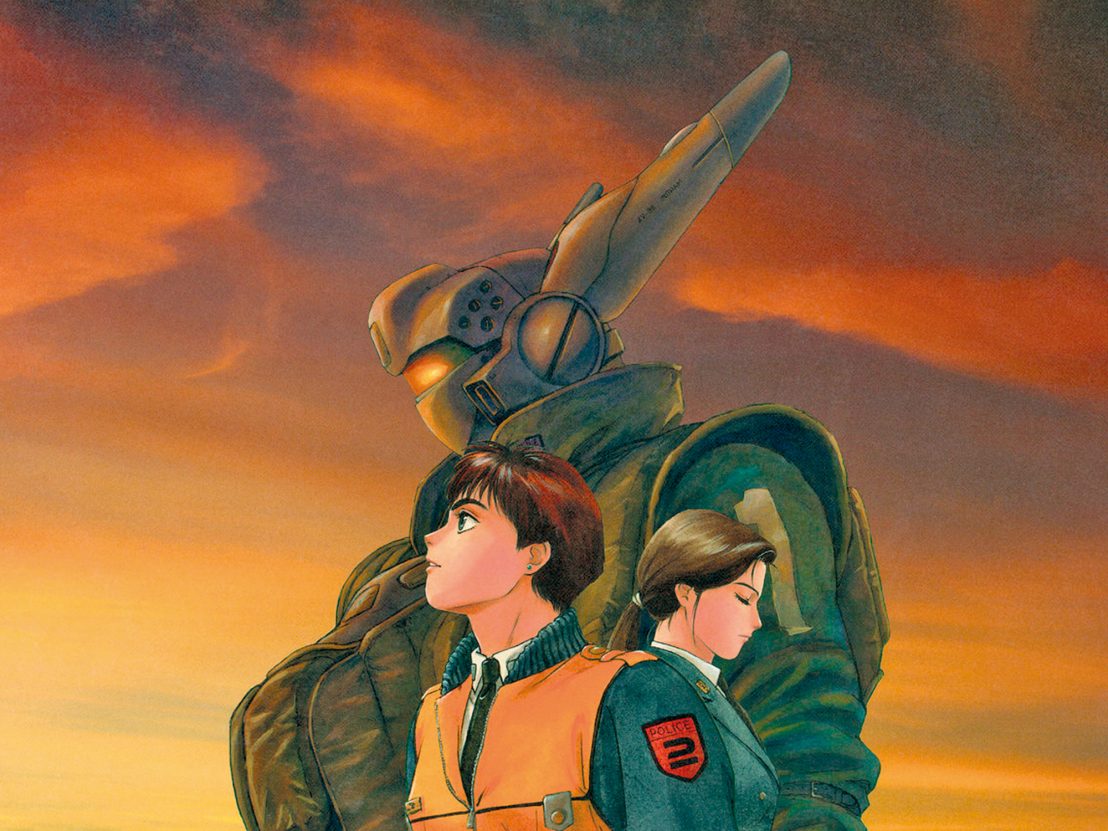

Patlabor: The Movie & Patlabor 2: The Movie

Mamoru Oshii has directed no shortage of masterful animated as well as live action films, and the Patlabor series stands proudest among them. Before Oshii made his vastly influential adaptation of Ghost in the Shell, he toyed with questions of technology and totalitarian government, post-human detective mystery and military action with the Patlabor series. Following on from the OVA – well worth seeking out and watching where you can find it – Patlabor: The Movie follows the characters of that short series into a surprisingly granular, procedural investigation involving the manufacturing of big robots and a potential software malfunction, and its far-reaching consequences.

The sequel, Patlabor 2, doubles down on the patient pacing and moody atmosphere of the first, but actually moves away from the first into a deeply involved political allegory for Oshii’s thoughts about post-occupation Japan and the actions of the Japanese Self-Defence Forces. The immense detail and surprising realism in its construction in its use of period-accurate technology alongside the fantasy of its mecha storyline and the complexity of its political themes make it one of Oshii’s most fascinating works. With little in the way of high-def home releases, the chance to see Patlabor in the cinema isn’t to be missed.

Liz and the Blue Bird

A critically-beloved work from Naoko Yamada, one of the best directors currently working in anime and anywhere else, Liz and the Blue Bird has remained somewhat elusive in UK home releases and cinemas until this point. A spin-off from the series Sound Euphonium, it focuses in on two of the show’s supporting characters Mizore and Nozomi, and a sort of unrequited love between them. As in her other works, Yamada’s film evocatively uses flower language in place of what the characters themselves cannot express, used alongside her close attention to body language and animated character acting.

Throughout, Yamada depicts Mizore and Nozomi’s recital of a musical piece from Liz and the Blue Bird, while visualising the fairytale itself that the music is based on through softer, watercolour textures. The coupling of the fairy tale to the real world is delicate and moving, but becomes completely overwhelming in the realisation of Mizore and Nozomi’s musical piece (composed by Sound Euphonium’s Akito Matsuda), their duet of oboe and clarinet representing these fictional characters as well as an expression of their evolving relationship.

Also showing is Yamada’s previous feature, the perhaps better-known A Silent Voice. Another heart-rending, visually ravishing endeavour worth seeing – with a number of the same creative talents on board.

Momotaro’s Divine Sea Warriors

It’s not just contemporary hits that should grab the attention in this season, but also some looks at the earliest examples of anime. The recently re-discovered and restored WWII propaganda film Momotaro’s Divine Sea Warriors – previously thought burned by the American occupation, as noted in Helen McCarthy and Jonathan Clements’ The Anime Encyclopaedia. Directed by Mitsuyo Seo, it was the first feature-length anime film, commissioned by Japan’s Naval Ministry after seeing Disney’s Fantasia. It’s influence was so that it inspired the career of Osamu Tezuka, the ‘Godfather of Manga’ and a major figure in shaping the anime industry into what it is today (for good and for plenty of bad).

Ironically, Seo was actually a leftist politically – the booklet for The Roots of Japanese Anime detailing his involvement with the Proletarian Film League of Japan – contradictions which makes Momotaro’s glorification of Japanese imperialism and colonialism morbidly fascinating (and reportedly, a lifelong shame of Seo’s). Similarly, a program of rarely-seen anime shorts details the way the form evolved in the early days of Japanese cinema, including Seo’s Ari-chan the Ant (1941), which shows how the filmmaker had already emulated Disney in his use of the multi-plane camera, these techniques helping lay foundations for the anime industry.

The BFI’s Anime season runs at BFI Southbank and BFI IMAX from 28 March – 31 May. Tickets for April are on sale now, tickets for May are on sale from 4 April.

Published 24 Mar 2022

By Giacomo Lee

Patlabor 2 and other classic-era sci-fi show the past, present and future of Japan’s capital.

By Anton Bitel

Metropolis, Rintaro’s 2001 manga spin-off, is coming to DVD.

This soulless documentary is an insult to subscribers who wanted to learn more about Japanese animation.