For Western audiences looking to engage more with Japanese animation, a documentary about the creators currently working in the anime industry may seem like a great addition to the Netflix catalogue. It’s a shame, then, that Enter the Anime – a documentary aimed at newcomers to the genre – has so little interest in the genre itself.

Netflix has made no secret of its plans to become a home for anime streaming, with a host of Netflix Original series – B: The Beginning, Aggretsuko, Devilman Crybaby, and more – looking to draw on an international audience that is increasingly well-versed in the genre. Not to mention its licensing of high-profile anime series like Little Witch Academia, Attack on Titan, or the seminal Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Even a decade or so ago, Japanese anime was very hard to get hold of in Western territories – as Cannon Busters creator LeSean Thomas puts it in Enter the Anime, anyone watching anime in the ’80s was probably doing so via bootleg VHS tapes. The fact that so much of it is now easily streamed through platforms such as Netflix, Crunchyroll, or Hulu is certainly something to be celebrated, but that doesn’t mean the platforms themselves are doing a good job of spreading the word.

Enter the Anime is one of the most half-hearted and disinterested documentaries ever to grace the service. It opens with its director, Alexa Burunova, admitting they knew little to nothing on the topic before Netflix commissioned them to research it, literally googling “what is anime?” in the documentary’s first few minutes.

But despite the search engines at Burunova’s disposal, his project never attempts to define its subject matter, or even begin to question the tokenistic way it breezes through the streets of Tokyo, exclaiming at a culture it lacks any basic awareness of – showing shot after shot of posing cosplayers while brushing off Japanese fan culture as “crazy”. The first quarter of the documentary is also over before a Japanese creator even appears onscreen.

There’s no mention of anime series that viewers might have already know, which could serve as an entry point to the discussion – say, Dragon Ball, or Attack on Titan, or Fullmetal Alchemist. It’s only at the end credits the reasoning becomes clear: “All anime titles covered in the documentary are available and now streaming on Netflix”. But Enter the Anime is actually even more selective than that, not bothering to mention a single TV series that isn’t produced by Netflix itself. (There’s a 10-minute tangent on a concert performer who sings the Neon Genesis Evangelion theme song, but the show itself is somehow never named.)

That’s not to put down the output of these Netflix-associated creators – including Cannon Busters’ LeSean Thomas, Castlevania’s Adi Shankar, and B: The Beginning producer Rui Kuroki (who worked on the iconic anime sequence in Kill Bill: Volume One). But even those interviewed are routinely asked irrelevant questions about their pets or favourite foods, rather than how their shows get made. There’s little interest in what makes anime anime, how larger Western audiences are influencing the kind of content being created, or the place that US creatives have in the industry.

At worst, Enter the Anime is two-fingered salute to Netflix subscribers who wanted to learn more about Japanese animation. At best, it’s an insufferable holiday blog. Both audiences and anime creators deserve better than this – and if Netflix wants to be a home for anime going forward, it needs to pay the genre a lot more attention.

Published 21 Aug 2019

By Giacomo Lee

Patlabor 2 and other classic-era sci-fi show the past, present and future of Japan’s capital.

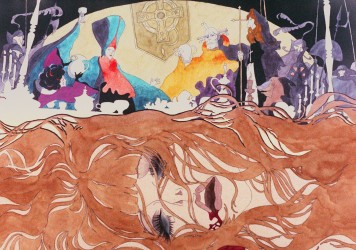

Look out for Eiichi Yamamoto’s transgressive epic from 1973, Belladonna of Sadness.

By Tom Dunn

With superhero movies reaching saturation point, it’s time more embraced the visual tone and texture of the physical medium.