The destruction of Tokyo looms large in anime cinema of the speculative variety. The Japanese capital is remade into Neo-Tokyo following the nuclear explosion that kicks off 1988 cyberpunk classic Akira, while cult animations of the same era such as Cyber City Oedo 808 play out in capital cities of their own making. A popular example is Ghost in the Shell’s New Port City, a fictional metropolis which comes without either the destructive backstory of its predecessors, nor the feel of Tokyo itself, designed as it was to be more of a stand-in for the state of Hong Kong.

For those looking for an actual sci-fi depiction of Tokyo, then, it’s best to look back at an earlier anime work, one related to the world of Ghost in the Shell, but of the entirely different Patlabor franchise. Released a few years before Ghost in the Shell, and coming from the same creative partnership of director Mamoru Oshii and writer Kazunori Itō, Patlabor 2: The Movie was both a follow-up to the 1989 original also put together by the duo, and a continuation of the equally child-friendly TV show of the same name. Despite there being no changing of the guards between films, the gulf in difference between Patlabor 2 and its previous incarnations could hardly be any bigger, with the 1993 movie eschewing the pattern of procedural-style plots for something of a more cerebral bent.

The Patlabor franchise centres around the crime-busting efforts of a group of human police officers and their fleet of so-called Patrol Labors, walking ‘mecha’ suits designed to keep the streets of Tokyo safe. The genius of Patlabor 2 is the delicate political narrative it manages to spin around these clunky robot constructions. While this in part is due to their very sparse use throughout the story, the absence of Labors soon comes to define the film, as tension rises in a version of Tokyo placed under military coup. Bridges are destroyed, citizens are trapped, whilst the police strive to work out who is really pulling the strings behind the siege. As the situation becomes more dire, the higher the need to deploy the last-resort of the mecha, whose military might is demonstrated through the violent flashback to a failed peacekeeping mission; just as high is the threat in them being rolled out by the enemy faction. Once again, we find the destruction of Tokyo looming on the horizon, with only the unwieldy power of technology to blame.

Speaking on the violence and violation upon Tokyo in the film, noted city and culture commentator Colin Marshall argues that Patlabor 2 “depicts realistic attacks on a realistic Tokyo for the same reason it has to minimise the screen time taken up by mecha fisticuffs – because of its aspirations to real-world relevance.” Such relevance is also helped by a vision of Tokyo in 2002 that’s very much like the Tokyo of 1993. For Marshall, the film while “set in the future – now, of course, long past – manages to keep the exaggerations of the then-existing built environment to an absolute minimum. No element of its depiction of Tokyo stands out quite as immediately as its realism.

This realistic city setting sits in well with Oshii’s aim to define what Japan stood for in the post-war and Cold War period. Patlabor 2 asks if the country’s future would or even should see it play more of a role on the military world stage, taking part in the sort of peacekeeping mission that haunts the bitter antagonist, a former soldier who has chosen to betray both city and country. Tokyo is used as a stand-in for Japan, a place literally and figuratively frozen between one era and the next, at a stand-still due to the siege, and soon covered in the first snows of winter. The film has the same stylistic flourish seen in GitS, conjuring a dreamy ambience from snowy city scenes and lingering shots of Tokyo’s industrial underbelly. The camera seems to act like one of the many birds that haunt the film, a hovering visitor surveying the city as it grinds to a halt.

From where present Tokyo ends in Patlabor 2, Roujin Z begins, a 1991 anime written by Katsuhiro Otomo, the auteur behind Akira, and directed by his assistant on that project, Hiroyuki Kitakubo. It’s also a film where the spectre of the mecha reappears, this time in the form of Z-001, an ultra-advanced hospital bed which houses the geriatric guinea pig Kijuro. The prototype houses, medicates and entertains the frail fellow like some kind of farm animal, in a demonstration on how to solve the problem of a city packed with elderly residents. This vision of early 21st century Tokyo is teetering on the edge of chaos, with young ‘stand-by’ carers summoned from around the city to any emergency at the push of a button; when old hands tap too much, the narrow streets become quickly clogged with city ambulances answering the call.

This urban chaos is heightened when, like in Patlabor 2, Tokyo’s industrial character is ultimately used against itself, with the rogue mecha and airplanes of the Oshii movie replaced by the everyday buildings and vehicles that populate Roujin Z’s Tokyo. In a style reminiscent of Akira’s climactic transmogrification scene, an out of control Z-100 begins to assimilate artificial features of the city, growing in size into a rampaging giant of patchwork scrappage. Otomo’s message couldn’t be clearer – Tokyo has grown phenomenally, but at the expense of all its residents, with young and old pitted against each other in a war for space and resources. As in Patlabor 2, the conflict is an internal one.

Similarly heightened in the movie is a tension between old and new, as highlighted in a flashback scene when Kijuro dreams of his deceased wife. This sequence is set in a more idyllic time, with a pastoral vision of Japan that restores all the humanity missing from Kijuro’s present day home. “Roujin Z’s depiction of the city is one of the old meeting the new,” agrees Isaac L Wheeler, cyberpunk author and Editor-in-Chief of influential cyberpunk site Neon Dystopia. “There are no massive sky scrapers, but there is a modern sense of sprawl,” he continues. “The urban landscape of shopping centres and cramped apartments juxtaposes against the countryside with its sense of calm – at least until the robots show up.”

In both animations, the spirit of the past can’t be escaped from. At play are different levels of Tokyo in simultaneous existence, giving what Wheeler finds in Patlabor 2 to be “a real feeling of history, of many hidden places that have come into existence.” This layering of past, present and future is what marks out these films as unique in the anime sci-fi canon. Destruction may lurk in familiar yet fantastic forms, but the construction remains – a gritty, breathing Tokyo, alive with realism, and not going away anytime soon.

Published 15 Jan 2018

Katsuhiro Ôtomo’s iconic anime mirrors the atrocities witnessed by Hiroshima and Nagasaki 70 years ago.

Rare shorts from 1917 to 1941 are now streaming in celebration of 100 years of anime.

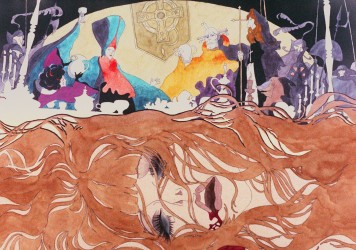

Look out for Eiichi Yamamoto’s transgressive epic from 1973, Belladonna of Sadness.