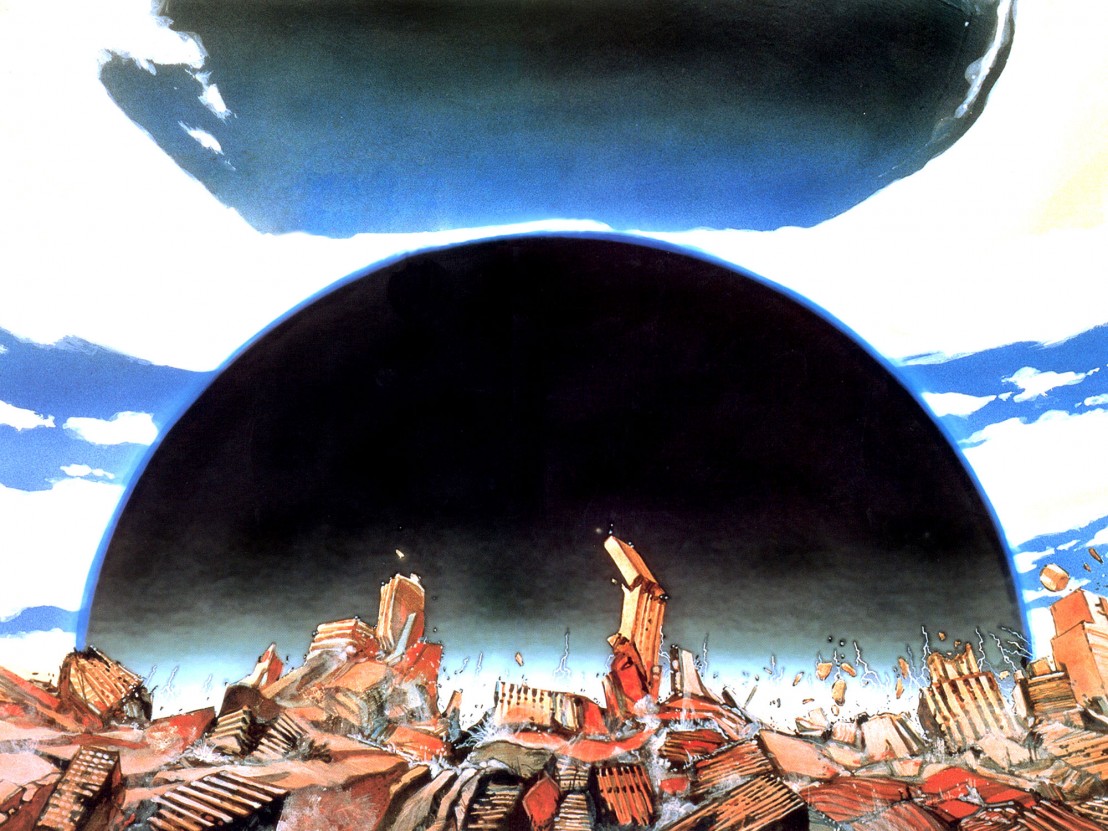

On 6 August, 1945, a nuclear bomb was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, instantly wiping out 40,000 human lives. Three days later, a second bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki, killing hundreds of thousands of people over the ensuing years.

In the American occupation that followed Japan’s surrender, all negative discussion of the bombings was prohibited. Instead criticism of the attacks found other cultural outlets, notably in Japanese art, literature and cinema, in particular the Godzilla (or Gojira) films. These iconic monster movies are steeped in skepticism towards science, criticism of the military and distrust of the government – the exact same motifs found in Katsuhiro Ôtomo’s classic anime, Akira.

In the years leading up to World War Two, the totalitarian Shōwa regime sought to crush opposition with executions and political assassinations across the Japan. Control was seized from political parties and distributed among admirals and military leaders, introducing a period of hyper nationalism. This political climate ultimately paved the way for Japan’s involvement in the War.

Military failures and government corruption are rife in Akira. Before the rise of Tetsuo, Neo Tokyo is a fascist state – protesters are violently suppressed by the militaristic police force in the opening scenes. This ineptitude of Colonel Shikishima’s military aggravates the tumultuous situation during Tetsuo’s rise to power, with a military coup ultimately handing control of the capital to Tetsuo’s gang of religious zealots.

In the aftermath of the bombings, hundreds of Japanese orphans were relocated to China – essentially abandoned by the incompetent Japanese government. The concept of a ‘lost’ generation is apparent in the hidden world of Takashi, Masaru and Kiyoko – a childhood grotesquely destroyed by the experimentation of the government. The children of the ‘Akira’ program are prematurely aged in appearance – forced to grow up much faster than their peers due to the policies of a self-interested and reprehensible government.

The atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima was nicknamed ‘Little Boy’ – a stunning parallel to the Akira character; a mute little boy and eventual harbinger of the destruction of Neo Tokyo. Just as Dr Manhattan typifies the otherworldly science behind nuclear technology in Watchmen, so Akira appears to represent the absolute power of the atom.

Another interpretation is that the concept (rather than character) of ‘Akira’ represents the atom itself. Kei explains in a conversation with Kaneda that – like atoms – Akira is present in all things. In this scene Kei makes direct reference to nuclear war, arguing that while amoebas contain the power of Akira, “Amoebas don’t make motorcycles and atomic bombs!” Her explanation as to the origins of ‘Akira’ draw similarities to the science of the Manhattan project: “before there were these men that tried to harness such energy… they failed and the destruction of Tokyo was inevitable.”

Following his exposure to ‘Akira’, Tetsuo begins to embody many of the physical and mental traits that afflicted radiation sufferers. The tablets he chokes down in a vain attempt to control the rapidly evolving power inside him are reminiscent of the useless vitamin tablets administered to survivors in the wake of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. This treatment was powerless to prevent the fatal secondary diseases and radiation that killed hundreds of thousands of survivors in the following years.

As Tetsuo’s power grows, his body explodes with extreme, hideous mutations – an exaggerated version of the thick, incurable keloids that developed on many survivors of the nuclear blasts. These rubbery, tumour-like lesions grew uncontrollably across the skin, becoming instant signifiers of the hibakusha, a stigmatised group who were perceived to have been corrupted by radiation. Fear and suspicion of the hibakusha led the sufferers of these mutations to be ostracised from the rest of Japanese society. This link between isolation and mutation is mirrored in Tetsuo’s descent into madness; his physical disfigurements worsen as his relationship with Kaneda and Kei breaks down, and the uncontrollable power within him takes hold.

Tetsuo’s ignorance of the destructive power he wields could be viewed as an allegory of the Manhattan Project as a whole. When they signed up, many of the scientists of the project were unaware that they were working towards the creation of a nuclear weapon. When the true meaning of their work was revealed, most continued on the project under the dubious belief their work was for the greater good.

Jerome F Shapiro explores the idea that nuclear war in movies can be seen to bring about positive societal change in his 2001 work ‘Atomic Bomb Cinema: The Apocalyptic Imagination on Film’. “The Apocalypse does not bring around the end of the world, but a crisis-like period of intense suffering that cleanses the world of evil.” The cataclysmic destruction of Neo Tokyo in the final scenes adheres to this ideology. It strips away the totalitarian government, criminal underworld, anti-government terrorism and religious fanaticism, leaving behind a blank canvas in which to begin again. The film ends in disaster, admittedly, but also in hope.

In reality, the dropping of the two atomic bombs brought only more hardship and horror to the people of Japan. In 1982, when Katsuhiro Ôtomo released the first of the iconic manga comics which Akira is adapted from, he was writing in a climate gripped by the tendrils of the cold war. As the doomsday clock crept closer to oblivion each day, it’s hardly surprising that his epic depicts a dystopian landscape of fear. Fear of the military, fear of corrupt politicians and the ultimate fear of apocalyptic nuclear destruction. Ôtomo’s Neo Tokyo is haunted by the ghosts of one of the darkest chapters in scientific discovery, where the only imagined future is a repeat of the unmitigated horror witnessed by Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Published 4 Aug 2016

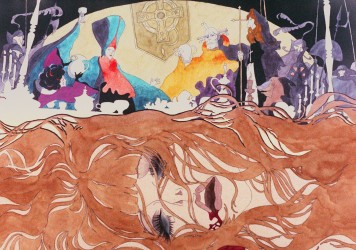

Look out for Eiichi Yamamoto’s transgressive epic from 1973, Belladonna of Sadness.

By Tom Graham

How Paul Schrader reinterpreted the fascinating story of the revered Japanese author.

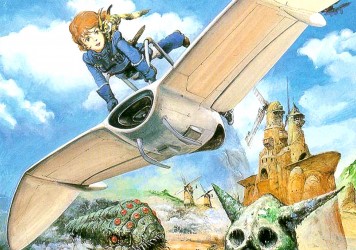

Gorgeous original artwork spanning three decades of the iconic animation studio.