The Inuit hamlet of Igloolik (population: 2,000) is situated on a remote island in northern Canada, which has a freezing polar climate typical of most of the Arctic Circle. Though small, the island is a cultural hub for a circus troupe, an arts festival, and one of the most exciting film scenes of the 21st century. The most renowned film to have emerged from this scene is Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, released 15 years ago to widespread acclaim and the recipient of the Camera d’Or at the 2001 Cannes film festival.

Atanarjuat is director Zacharias Kunuk’s adaptation of an epic Inuit legend about jealousy, evil spirits, revenge, brotherhood and redemption. Set roughly 2,000 years ago, the film is unlike anything else that world cinema has to offer, and in order to really appreciate its impact it’s important to take a closer look at the town that created it.

Firstly, there is a sensory richness that stems directly from the film’s stunning Arctic setting. The crunch of snow underfoot, the glint of low sunlight on ice, and the empty white horizon all provide a unique visual framework for the story. Kunuk’s filmmaking style is striking, too. His camera stays close to the actors, capturing every detail of their faces, and everyday rituals are shown in their entirety to demonstrate the Inuit people’s astounding methods of survival in this unforgiving landscape.

It’s also worth noting that the film was made by Isuma, a production company set up with the sole aim of fostering indigenous community cinema in Igloolik and beyond. All of the film’s costumes, props and sets were made locally. The story had been passed down orally for generations, so it was crucial to consult Inuit elders to fully understand it, as well as to flesh out the finer details of nomadic Inuit life. During production, Kunuk took his crew out onto the tundra to create an open community atmosphere. Even the catering department was a team of hunters, who would bring back animals caught on the ice.

All of this auto-ethnographic background work makes for a film steeped in authenticity and intrigue. The Arctic, a place stereotyped and feared by most non-Inuit people, is demystified so that its inhabitants can tell a meaningful story in their own words. Moreover, Isuma’s grassroots approach has a tendency to spread. Not only have they changed the economic landscape of isolated northern communities, but they also host an online portal for indigenous storytelling that boasts media from all over the world in more than 80 languages.

After its initial release, some confused reviewers referred to Atanarjuat as a documentary. This speaks to the general ignorance around Arctic Canada, but also to the film’s faithful attention to traditional Inuit practices. Indeed, the sense of ‘realness’ is what stands out most about the film, not least in a pivotal action sequence in which the title character runs for his life across sheets of ice completely naked. It’s a riveting set piece and an ingeniously cinematic way to bring the location to life.

This year, Kunuk premiered his latest film Maliglutit (Searchers) at the Toronto International Film Festival. It takes its name from John Ford’s famous western, but Kunuk has not compromised his singular vision for a Hollywood version of indigenous life. He is continuing the movement that Atanarjuat launched of Inuit self-representation and vibrant community cinema.

Published 20 Sep 2016

Mr March of the Penguins returns with an affecting, unhysterical film about the ensuing climate disaster ahead.

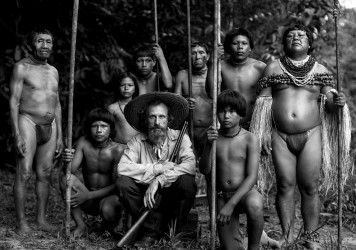

Ciro Guerra’s film is a stark reminder of the destructive nature of European colonialism.

Werner Herzog goes head to head with the volcanoes of the world in this new, globe-trotting doc.