It’s easy to laugh at how parochial it seems, but the joke is on us: nationalism, the most remote end point from the prevailing move towards a globalised world without borders, is not just alive and well but experiencing a formidable surge in popularity. The result of the recent UK EU referendum is proof of this: for an increasingly disenfranchised population, nothing could be more perfect for the projection of its crushing anxieties and resentment than the menacing, unknowable other.

In his seminal text ‘Imagined Communities’, Benedict Anderson observes: “the fellow members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow members, meet them, or even hear of them… communities are to be distinguished not by their falsity or genuineness, but in the style in which they are imagined.” However poorly defined it may be, however steeped in the problematic legacy of imperialism, the notion of “Britishness” has shown itself to be a powerful glue for the collective imagination. In the fallout of Brexit, as we drift towards an uncertain future, what lessons on nationalism can we draw from cinema from around the world?

First, it’s important to distinguish between the films that explicitly set out to glorify the idea of the nation, and the ones that qualify as commentary on the political realities of the nation – such as Alfonso Cuarón’s Y Tu Mamá También or Wolfgang Becker’s Good Bye, Lenin! Throughout its history, cinema has been harnessed to tell grand tales about the fight against perceived threats to the cultural values that are cherished by a community. From the earliest examples of nationalist film, such as DW Griffiths’ The Birth of a Nation and Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, we have learned that there is a specific trajectory to be followed when it comes to the construction of national identity. In Battleship Potemkin, the valiant crew of the eponymous ship leads fellow citizens in Odessa in a historic mutiny against the despotic aristocracy. A memorable scene where the men refuse to eat yet another maggot-infested meal exemplifies the turning point where subservience to authority is suddenly transformed into rebellion.

While Eisenstein’s relationship with the Soviet Union was ambivalent, the intention of this scene is clear. The aristocracy, which has for centuries been the source and symbol of Russian pride, has become rotten – much like the meat that the men are being forced to eat. A new way of being and thinking – a new understanding of what it means to be Russian – must be found. For the Bolshevik revolutionaries, riding on a wave of civilian discontent, Communism was to be that replacement. It is no wonder that Lenin described cinema as being the most important of all art forms in the Soviet Union. He was right: it is a direct call to arms, it urges the audience to extend sympathy and allegiance to a specific group that they are meant to identify with, while vilifying another.

While nationalism can be about many things, the most successful films on the subject tend to focus on the fight for freedom and self-determination. Walter Salles’ The Motorcycle Diaries, although not about any one country in particular, captures Che Guevara’s passage towards Marxism and the zeitgeist of 1950s Latin America. Remember the famous scene in Casablanca where the crowd breaks into a rousing rendition of ‘La Marseillaise’, drowning out the Nazi officers’ attempt to sing ‘Die Wacht am Rhein’? These are all very attractive stories about the war against oppression that are valuable in their own ways, but they also define the search for national identity as a primarily masculine project with a military character. If film is to genuinely goad us towards a bolder, more thoughtful vision of what the contemporary nation state is and can be, we must begin privileging stories that are less reductive.

Already, cinema is making the encouraging shift towards a less monolithic, more fragmented representation of nationhood. Take Abbas Kiarostami’s Ten, for example, which documents the conversations between a female driver and her various passengers as she drives around Tehran. Their casual small talk may not amount to much on the surface of things, but these conversations reveal plenty about everything that comprises Iranian politics: gender relations, religion, the thorny relationship between the will of the body politic and the will of the state.

Abderrahmane Sissako’s Timbuktu explores how the city’s residents dealt with occupation by the extremist group Ansar Dine, without ever veering off into pointless hysteria in its depiction of resistance. In one scene that is at once humorous and wrenching, a group of young boys simulate a football game with an imaginary ball, skirting around newly-imposed laws that ban all balls from the city. Elsewhere, Céline Sciamma’s Girlhood rejects popular depictions of the French banlieue that focus mainly on antagonistic, alienated young men, choosing instead to look at the lives of non-white French girls growing up in a country that has been slow to address their troubled predicament.

Certainly, these films continue to depict the victim-aggressor relationship between various subjects, but they don’t do it in a simplistic way. The exploration of national identity is a tough one that brings about tension and suffering, but it doesn’t always have to be confined to vignettes of revolutionised men with guns or spies dying for their countries. There are infinitely more meaningful ways to describe how one is French, or Iranian, or Malian, or a citizen of any other country in the world.

At its genesis, nationalism necessitated a peculiar type of homogeneity, an absolute sense of belonging that has now become impossible given the fluidity of people and places. Only through cinema could these fantasies be fully realised, and so film can be understood as the ultimate nationalist project. Yet reality is far less convenient than the heroic seizure of power from tyrants into the deserving hands of the masses. These sweeping narratives submerge any nuanced attempt at understanding the modern complexities of nationhood outside of a false dichotomy that pits the ruling elite against the people. There are other messy relationships that we must unpick and other important stories about ordinary lives that must be told: these are often richer, more interesting, and just as overtly political.

Published 6 Jul 2016

The French director of A Prophet and Dheepan is drawn to stories of human resistance and struggle.

By Sam Thompson

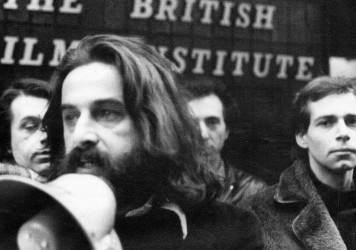

Radical socialist filmmaker Marc Karlin emerged as a key counterculture figure in the 1970s and ’80s.

By Beth Perkin

Collectives like the WFC are providing the tools to enable people around the world to create meaningful connections.