Marc Karlin hated silence. His films are a protest against the passivity of repressed history and compliance with injustice. Born in Aarau, Switzerland in 1943, it was 1960s Paris that taught him to speak. The near-revolutionary events of the summer of ’68 gave him something to say, and tutelage under film essayist Chris Marker gave him a language.

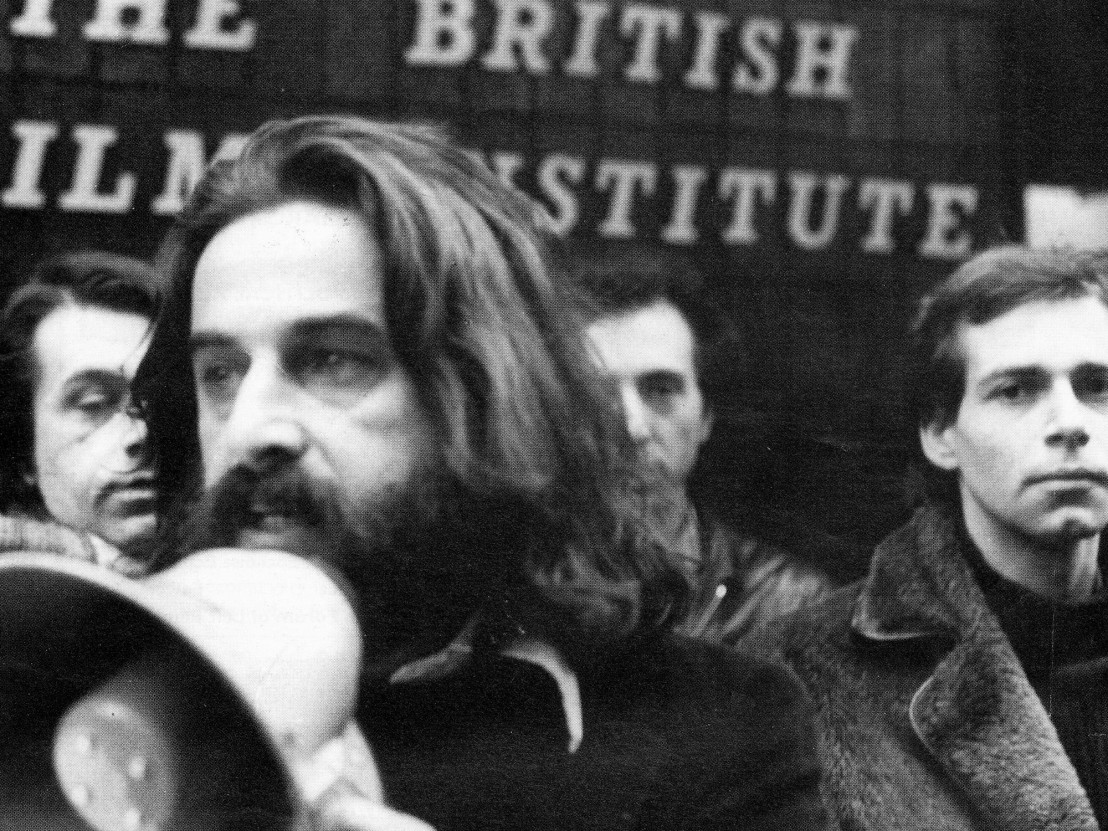

Plunged back into the left-wing cultural explosion of 1970s London, Karlin founded the Berwick Street Collective. In ’75 the group produced Nightcleaners, a portrait of black office cleaners and their attempts to unionise – now considered a landmark in co-operative cinema. From 1983 to 1999, Karlin directed 12 films, most of them for Channel 4 (then the dicey young-guns of British television). A recent Karlin retrospective at the month-long AV Festival in Newcastle upon Tyne gave some of these works their first ever cinematic outing. A committed radical artist, Karlin would have been delighted by the theme of this year’s festival, ‘Meanwhile, what about socialism?’, taken from George Orwell’s ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’.

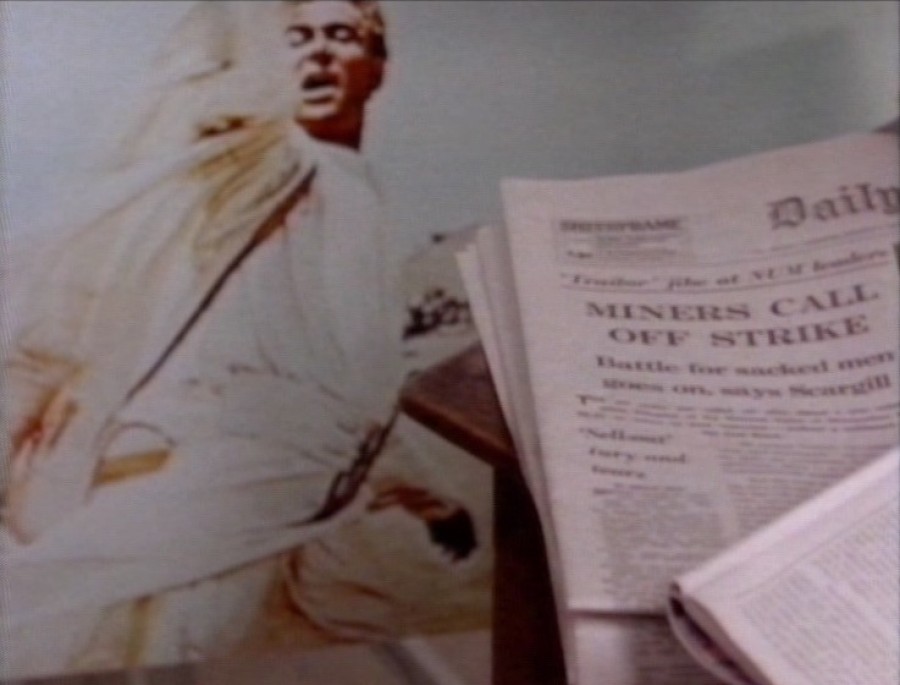

The global uprisings of 1968 were the last time the left united under a red flag. This claim (whether you believe it to be factual or not) encompasses many of Karlin’s key concerns. First, there’s the state of the left since ’68: the fragmentation, defeats and reformations; its failed revolutions and future strategies. In 1987’s Utopias, Karlin presents seven visions for socialism. Two of these connect directly to the 1984-85 miners’ strike – a co-operative upholstery business run by blacklisted pitmen, and a campaign to keep a local colliery open. The question that hangs over these testimonies is: how can the left continue united after such a huge defeat?

This leads to another question: what symbols does the left still have to unite under? Is the era of the red flag over, and if so is our collective history irrelevant? Karlin addresses this (albeit indirectly) in his 1993 film Between Times. Two narrators – ‘A’ and ‘Z’ – debate the future of socialism. A believes that we must salvage the remnants of the past, eulogising about a pre-Thatcher world of working class culture and struggle; Z argues for moving on – the best we can hope for is a ‘politics for the redemption of time’, in other words to be as free from work as possible. A believes in progress founded on an understanding of history; Z is convinced history is cyclical, progress an illusion.

A’s project – to negotiate his affection for the past with the need to forge the future – is made flesh in 1986’s For Memory. Karlin tracks the left’s shared victories and traumas, from the Liberation of Belsen to resistance against British fascism, via Francis Drake, colonialism and romantic poetry. We journey to a Yorkshire pit town, where a photography exhibition details life in the 1930s. The curator – a zealous protector of proletarian history – explains the social relations hidden in the photos. Marxist historian EP Thompson lectures on the British radical tradition, then attends a memorial service for the three mutinous Levellers executed in 1649. A Jewish Eastender recounts the Battle of Cable Street, a folkloric victory against fascism, as the camera cuts to the preparation of a commemorative mural. These strands of memory and symbolism may seem like wistful navel-gazing, but their importance has never been more relevant. The current Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn is a romantic socialist – his ascendency is, in part, thanks to a constituency that are still moved by the ‘scarlet standard’. Karlin’s films press this constituency to assess whether the traditional symbols of the left still have a place in post-Thatcher Britain.

There were three prime movers of 1968: radical students, trade unions and the free love libertarians. While these causes splintered and diverged after 1979, Karlin retained the best of each of them – revolutionary socialism from the students, a concern for working class life from the unions, and an open dialogue with second wave feminism from the libertarians. In the context of insurrection and industrial action, Karlin’s feminist leanings are easy to neglect. But appreciating their importance is paramount to understanding the kind of politics he strove for.

In 1985’s Nicaragua, a series of four films chronicling the uprising against the repressive Somoza regime and the subsequent civil war between the Sandinista government and US-funded contras, Karlin finds female voices both inside and outside the revolution. They’re artists, activists, archivists, leaders, workers and mothers. One peasant, widowed but still working the land, explains how life after the Sandinista revolution is tough; she’s considered remarrying but finds single life liberating. Together, the Nicaragua films possess both the historical rigour of Patricio Guzmán’s The Battle of Chile and the philosophical ambition of Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing; they are the work of a poet disguised as a pamphleteer.

Women also enrich and add nuance to Karlin’s account of trade union decline. In a scene from Between Times, a worker for a data-processing company describes how the job’s flexibility suits her caring responsibilities. One of the most distinct voices in Utopias is Marsha Marshall, a miner’s wife who describes how most organising groups made her feel intimidated and inferior. Karlin gave space to female experience that contradicted traditional left-wing strategy, and he was happy to find the left wanting.

The sets and dioramas that populate Karlin’s films borrow from a dramatic tradition, stretching from Punch and Judy to German Expressionism. His films are literary, with chapters, text and references to Milton and Blake; they contain narrators who problematise authorship, refracting the story through multiple perspectives. But above all, Karlin’s work is cinematic. He was a master of superimposition, and brought drama to still images (long before Asif Kapadia was winning Oscars for it). And, like the French New Wave directors he idolsied, Karlin was a pioneer of the tracking shot.

The closest Karlin came to a pure cinema that blurs the boundaries between essay, documentary and narrative was in his late-period shorts. The Serpent, an hallucinatory indictment of middle class collusion in the media, tells the story of an architect who dreams of getting inside Rupert Murdoch’s ear. It’s dense with film references, from Luis Buñuel to Jean Cocteau, Powell and Pressburger and Andy Warhol, and makes Charlie Kaufman’s aesthetic look conservative and bland by comparison. Despite directing films exclusively for television, Karlin undoubtedly expanded our film language. He demonstrated the poverty of most documentaries, which through plainness try to convince us of their authenticity.

Restless, Karlin would find motifs and discard them. The image of a spinning die bookends the first chapter of Nicaragua: Changes, and then it’s simply rejected. Karlin finds these powerful visual metaphors, identifies their inadequacy and moves on. But it’s a mistake to see this digressive tendency as whimsy. Nothing is final in Karlin’s films. Everything is under revision, because so is the revolution – it continues, perpetually, even after the revolutionaries claim victory. Film is understood as a process, which is why Karlin favours tracking over panning. The pan can go 360 degrees and purport to show us everything, but when the track ends it implies that there is more left outside the frame. The pan gives liberation a completeness which it never possesses. In the 1980s, tracking shots were considered too stylised for documentary; in For Memory, Karlin goes to a dementia ward and tracks, for several audacious minutes, objects that feed the patients’ nostalgia – bobbins, a docker’s hook, a tin of Lyles’ Golden Syrup. In this context, tracking is radical.

In Nicaragua: Making of a Nation, marching Sandinistas chant the refrain ‘no one can take away my right to make demands.’ Karlin seeks to complicate our dreams. He finds inconsistency and complicity. Rarely does he solidify our hopes into propositions. (Does it even make sense to request that memory be sown into the fabric of utopias, and utopias into the fabric of memory?) When they do come, Karlin’s demands are diffuse and contradictory, but one shines through in its urgent sincerity: the demand for a revolutionary cinema.

AV Festival runs until 27 March across Newcastle and the surrounding region. Find out more at avfestival.co.uk

Sam Thompson is editor of Whitey on the Moon

Published 11 Mar 2016

By Mark Asch

Robert Eggers’ film provides an evocative reminder of the anxieties, fears and early religious beliefs that shaped the New World.

Love You To Death immerses the viewer in the powerful and revealing stories of bereaved families and friends.

Time Out of Mind, which sees Richard Gere sleeping rough, offers a refreshingly honest and sympathetic depiction of homelessness.